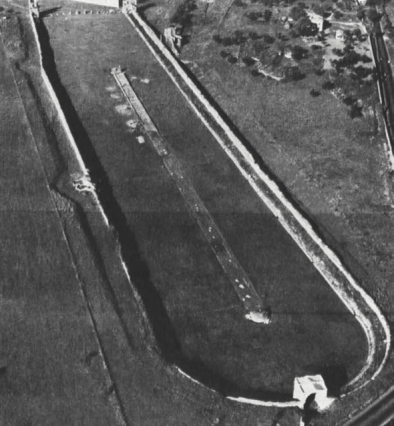

Circus of Maxentius. Near Rome, about 306-312

This best preserved of all Roman circuses was erected in a valley on the east side of the Via Appia, less than three miles from Rome. It was associated with a contemporary mausoleum, facing the road, and with an earlier hillside villa that was remodeled when the circus was built. The builder was the emperor Maxentius, who presumably occupied the villa in his lifetime. His burial in the mausoleum, though doubtless intended, was precluded by his damnatio memoriae in 312, but his son Romulus, who died in 309, may have been interred there.

The Circus of Maxentius closely resembled other Roman circuses in form, for the type became standardized through use (primarily chariot races) and by the influence of a famous prototype, the Circus Maximus, which adjoined the imperial palace in Rome. Characteristic features included the U-shape, with starting gates (carceres) at one end and a ceremonial archway (porta triumphalis) in the curved wall opposite. The carceres were often flanked by towers (oppida), between which was a terrace with a loge for the sponsor of the contest, who signaled the start of the races by dropping a mappa. There was also a judges' box near the finish line (on the south side in the Circus of Maxentius) and another loge for the emperor, often, as here, connected with his residence via a corridor.

The public—numbering here up to 15,000—sat around the "U" on benches borne on ramping barrel vaults that connected the double perimeter walls. Large gates were included (here, behind the oppida) for the entry of the pompa, the pagan religious procession with which each racing day began. The arena was divided by a spina, with conical metae signaling the turning points at each end. On the model of the Circus Maximus (vividly illustrated in a contemporary mosaic at Piazza Armerina, no. 91), the spina was adorned with fountains, honorific statues, and an obelisk.

Refinements of the basic circus design include the bent axis of the south wall, the slightly oblique alignment of the spina, and the asymmetrical disposition of the carceres. Such devices promoted safety and fairness by reducing crowding at the beginning of the first lap and at the turn, and by making the distance from gate to breaking line equal for all contestants. Late Roman constructional innovations are also present, including the facing of the concrete walls in alternating layers of brick and tufa blocks, and the incorporation of large hollow jars ("pignatte"; comparable to tubi fittili, no. 593) to lessen the weight of the vaults.

The conjunction of circus, villa, and tomb was unique in late antiquity, although the villa-cum- tomb alone was quite familiar (see no. 104). The presence of the circus is probably explained by the imperial ownership of the villa, for circuses were important adjuncts of the palaces in all imperial capitals of the day. The ludi circenses were traditionally religious, as well as sporting, events, celebrating the gods (among whom, after 309, was numbered Romulus) and the increasingly godlike emperor, whose appearance to the chanted acclamations of the crowd was a significant part1 of his ritual.

Date added: 2025-08-01; views: 314;