United States Capitol (1793-1863). Capitol Hill Washington, D.C.

William Thornton, Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Charles Bulfinch, Robert Mills, Thomas Ustick Walter, architects

The United States Capitol— “the spirit of America in stone”—achieves greatness in spite of its oft-troubled and interrupted history (which includes burning). Its Classical influence and its spirit of boldness—even its use of cut stone instead of brick as a facing material—were of enormous importance in the development of the young country, and the lengthy evolution of its construction is itself fascinating. As Glenn Brown put it in his monumental two-volume History of the United States Capitol, “The Capitol is not a creation, but a growth, and its highest value lies in the fact that it never was, and it never will be, finished” (Government Printing Office, 1900). Moreover as the father-image of most United States state capitols, it was, of course, of seminal importance.

The construction of the building covered four major and several minor stages. The first occurred in 1792 when Thomas Jefferson, with President George Washington’s approval, proposed a competition for a capitol. The winning design was that submitted (late) by William Thornton, a West Indies-born, Edinburgh-educated, non-practicing doctor with an impressive range of interests, including a surprising (for a self-taught amateur) grasp of architecture. Jefferson said of the winning project, “It is simple, noble, beautiful, excellently arranged” and “had captivated the eyes and the judgment of all” (quoted in I. T. Frary, They Built the Capitol, Garrett and Massie, 1940).

The principal element of Thornton’s sophisticated design was a prominent porch with eight Corinthian columns, simple pediment above, and low dome on stepped drum—highly similar to the Roman Pantheon (a.d. 124). But as Thornton was not a professional architect, troubles arose to plague the building’s erection, many continuing to the present day. Stephen (Etienne Sulpice) Hallet, a capable French-born architect, who had won second prize, was appointed superintendent of construction and he immediately attacked the technical inadequacies in his rival’s plans. He was discharged in November 1794 for taking “excessive liberties” with Thornton’s design. George Hadfield, a promising English architect, succeeded Hallet but he lasted only until May 1798. Work, however, continued and Congress occupied one wing (the north) in 1800. The building’s construction was managed by three commissioners—of which Thornton was one—until 1802.

Stage two commenced in 1803 when Benjamin Henry Latrobe, a highly trained English architect and engineer, was made surveyor of public buildings with the chief responsibility of completing the Capitol. Latrobe completed the House wing and repaired the Senate wing, which at the time were connected by a covered walkway with no central portion built. He also introduced his imaginative “corncob capitals.” Then in 1814 (during the War of 1812) the British burned the building, and the next year Latrobe was charged with repairing what he termed “a most magnificent ruin.” As Talbot Hamlin remarked, “The burning of the Capitol... was architecturally far from an unmixed catastrophe. It gave Latrobe a free hand in rebuilding much of the interior, while preserving Thornton’s exquisite walls” (Greek Revival Architecture, Oxford University Press, 1944). Latrobe redesigned the hall of representatives (now statuary hall), completed the two wings, as mentioned, and made drawings for the central domed mass and added cupolas—really low domes—over each wing. However, he, too, encountered disagreements and resigned in November 1817. He died three years later of yellow fever while supervising engineering work in New Orleans.

Stage three began in 1817 when President James Monroe, on seeing Charles Bulfinch’s famous Massachusetts State House in Boston (see page 133), persuaded Bulfinch to come to Washington as architect of the Capitol. Bulfinch first finished some repairs needed on the Senate and House (Congress moved back into them in 1819), and in 1818 began construction of the central portion, thus joining the hitherto lonely wings to make one substantial building; the rotunda link was finished in 1826. Most of the work that Bulfinch designed followed Latrobe’s earlier sketches, but when it came to the dome that Thornton had originally drawn up, Bulfinch was pressured by the president and cabinet to make it higher.

This was done with results that suggest an unhappy compromise between the dome of the Roman Pantheon and that of Bulfinch’s own Massachusetts State House. Bulfinch also designed the west front, on the Mall side, that also recalls his state house, and landscaped the grounds. The Capitol then entered a tranquil phase from 1829 until the mid-i85os. Robert Mills, who had won the competition (1833) for the Washington Monument (see page 216), became architect and engineer for the government in 1836; his occasional concerns with the Capitol were heating, ventilating, lighting, and acoustics.

By 1850 the rapidly growing country needed more space for its governmental offices, and Congress approved a competition for the Capitol’s extension. Though five prizes were awarded for this, the results were inconclusive, and President Millard Fillmore appointed Thomas Ustick Walter on 11 June 1851. Walter designed the two large additions for the House (occupied in 1857) and the Senate (occupied 1859), placing—with great skill—their axes at right angles to the main axis of the building and connecting them with proper hyphens. Equally important, he replaced the copper-sheathed masonry and wood dome, which Bulfinch had designed, with one far higher and bolder, made of cast iron (1855-65).

Walter realized that his broad extensions, which almost doubled the building’s length—to 725.8 feet/221 meters—and nearly tripled its size, demanded a higher dome to maintain proper proportions. For maximum buildup, he placed the dome on a two-story pilastered drum encircled by a one-story peristyle. Walter, with Montgomery Meigs the supervising engineer and August Schoenborn his assistant, wanted to build the dome’s structure of iron for fire protection. However, as Carl Condit points out, “The only example of an iron-framed dome in existence at the time was that of the Cathedral of St. Isaac in St. Petersburg, Russia” (American Building Art, Oxford University Press, 1960).

Walter, Meigs, and Schoenborn therefore carefully studied the documentation on the Russian structure and came up with their daring result. They were also highly influenced by St. Isaac (1817-57)—with its multitude of freestanding columns—in the design of their drum. The Washington dome, beautifully engineered, consists of two cast-iron shells, a high one for exterior silhouette nesting over a low one for interior scale (originally a concept of the Italian Renaissance). The Capitol dome, while a structural triumph, is for some finicky on the interior, especially in its coffering. It lacks the boldness of concept behind its hidden structure.

Except for a few details the Capitol was finished in 1863 and Walter—during another power struggle—resigned two years later. The building remained basically untouched until 1959-62, when the east front was extended 32.5 feet/9.9 meters. The length of time taken to complete the Capitol is underscored by the fact that three of the cornerstones were laid by presidents in three different centuries: Washington, 1793; Fillmore, lateral extensions, 1851; and Eisenhower, east front extension, 1959.

Frederick Law Olmsted was in charge of landscaping the Capitol grounds from 1874 to 1892, including the addition of the terraces. Thomas Wisedell, an architect, worked with Olmsted on the design of the west stairways and terraces.

Chief among the artists who decorated the interior of the building was Constantino Brumidi (1805-80), an Italian who spent twenty-five years working on the Capitol, most conspicuously in the rotunda. His fresco, The Apotheosis of George Washington, which fills the concave canopy of the dome, was very enthusiastically received upon its completion in 1866.

Brumidi also began the great 8-foot-/2.4-meter-high frieze around the base of the Rotunda dome. This depicts highlights in the history of the nation from its “discovery” by Christopher Columbus to William Penn’s treaty with the Native Americans, begun by Brumidi and continued after his death by Filippo Costaggini. Allyn Cox completed the frieze in 1953 with a representation of the Wright brothers at Kitty Hawk. Some of the corridor decorations in the first-floor Senate wing tend to flamboyance and—for some—questionable taste. And if, as Talbot Hamlin wrote, the statuary hall is marred “by some of the world’s least appealing sculpture,” it ranks as a detail. Architecturally there are many moments of grandeur in the Capitol of the United States.

Paint Evolution: History, Chemistry & Safety in Modern Interiors

In this chapter, you will:

- Analyze the social and physical influences affecting historical changes in paint and its application

- Recognize the importance and components of flame-retardant paints, active devices that alert occupants to smoke, and devices that extinguish flames

- Explain the interaction of color with materials, texture, light, and form—and analyze the impact of color on interior environments

- Distinguish between solvent-based and water-based paint—and understand methods for applying paint to a variety of surfaces

- Discuss the importance of industry-specific regulations and federal law related to paints and wallcoverings

The earliest known paintings were found in the Lascaux caves in France and in the Altamira cave in Spain and date from as early as 15000 bce. A thousand years later the Egyptians were making colors from soil and importing dyes such as indigo and madder. To this they added materials that are sometimes found in the paints that artists use: gum arabic, egg white, gelatin, and beeswax. The Egyptians also developed varnish from gum Arabic around 1000 bce.

It is only since 1867 that prepared paints have been available on the American market. Originally, paint was used merely to decorate a home, as in the frescoes at Pompeii, and it is still used for that purpose today. Modern technology, however, has now made paint both a decorative and a protective finish. Paint is commonly defined as a substance that can be put on a surface to make a film, whether white, black, or colored. This definition has now been expanded to include clear films.

The colors used are also of great psychological importance. (See Figure 2.1.) A study by Johns Hopkins University showed that planned color environments greatly improved scholastic achievement. Most major paint companies now have color consultants who can work with designers on the selection of colors for schools, hospitals, and other commercial and industrial buildings. Today, paint is the most inexpensive method of changing the environment.

Fig. 2.1 (a) Grey-blue gives a cool neutral background. (b) A green room has a cool ambience. (c) These vibrant colors give an active feeling to the room. (d) Yellow provides a warm cheery atmosphere. Photos courtesy of The Glidden Company

Components of Paints. Lead was a major ingredient of paint from 1900 through the 1950s. Today's paint, though, represents a major departure from the paint of the early twentieth century. Recognizing the dangers of lead in paint, the Consumer Product Safety Commission has prohibited its use since 1978.

Today's paint includes four basic ingredients:

1. Pigments, which give color to the coating.

2. Binders, which act like glue to hold the pigment particles together and provide washability/scrubbability, chemical resistance, durability, and other properties.

3. Solvents, which make the coating wet enough to spread on the surface.

4. Additives, which perform special functions.

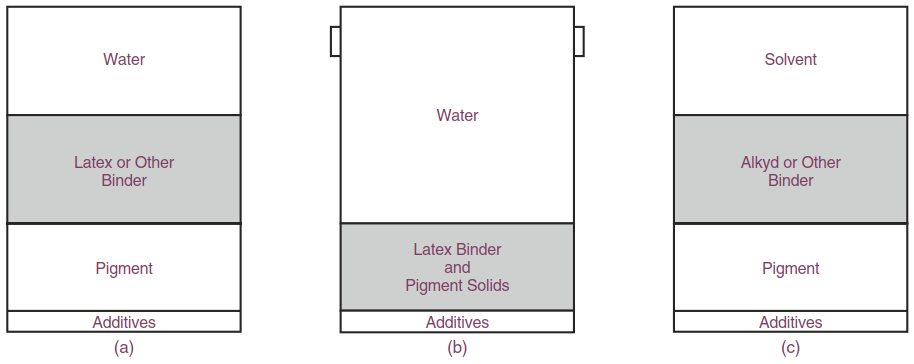

A typical coating product contains some or all of these ingredients. (See Figure 2.2.)

Fig. 2.2 Components of paint. Ingredients in (a) quality latex paint, (b) low cost latex paint, and (c) quality alkyd paint. Drawing courtesy of Builders Guide to Paints & Coatings, NAHB Research Center

Pigments. Pigments consist of powdered solids (such as titanium oxides and silicates) that give the coating its color and brightness qualities. These solids are important not only for their color, but also for their hiding ability. Generally speaking, the more pigment contained in a coating, the better it will hide, or obscure, the surface.

Different pigments have different purposes. Titanium dioxide is the best white pigment for hiding power. Extender pigments, such as calcium carbonate, are inert. Masonry paints have a larger percentage of calcium carbonate than other paints. In flat paints, extenders improve sheen, uniformity, and touch-up capability. In eggshell and semi-gloss paints, extenders affect gloss.

Binders. Binders are liquid adhesives (such as alkyd, resin, latex, and urethane) that form a film of pigment particles on the surface. These sticky resins and other adhesives are the vehicle for binding the pigments to the surface, creating a strong and durable bond. Thus, the strength of the binder contributes to the useful life of the coating.

Paints are generally classified as either solvent-based or water-based. Drying occurs when the water evaporates in water-base coatings, which are also known as latex coatings. Alkyds are coatings produced by reacting a drying oil with an alcohol.

Drying of the surface occurs by the evaporation of the solvent; curing of the resin occurs by oxidation.

Solvents. Solvents are liquids (such as water and mineral spirits) that make the product easier to apply. Sometimes called thinners, solvents "carry" the other ingredients over the surface. Without solvents, the paint would be thick as molasses. The solvent helps the coating penetrate the surface and then evaporates as the coating dries. Solvent-containing coatings can be used safely if overexposure is avoided and proper protective equipment is used.

The disposal of all types of coating materials is controlled by government regulations. Benjamin Moore has some useful tips for dealing with and disposing of leftover paint.

- Do not order more paint than is needed.

- Use all the paint you buy—an extra coat will give more protection.

- Leftover paint can be donated to a local charity, community beautification or service program, or neighborhood group that is assisting the elderly, disabled, or disadvantaged with the maintenance of their homes. Make sure the product you donate is in its original container with the label left intact.

- Leftover paint should never be poured down household sinks, toilets, or storm sewers. To dispose of latex paints, leave them to dry completely by removing the lid and allowing the water portion to evaporate. This should be done in an area that is away from children and animals. In most states, the container can then be disposed of in your household trash. Leave the lid off the can so that the disposal hauler can see that the paint is hardened.

- For disposal of solvent-based paints (alkyds or oil-based), contact the local or state government environmental control agency for disposal guidance.

Additives. Additives are special purpose ingredients (such as thickeners and mildewcides) that give the product extra performance features. The combination of these basic four ingredients is what creates a particular type and quality of coating.

For example, mildewcides reduce mildew problems, which are a major cause of paint failure. Mildew is a fungus that thrives in good growing conditions—food, moisture, and warmth. Several mildew-cleaning solutions are available, the simplest of which is bleach and water.

To comply with the VOC emissions laws, more solids are being added, which makes the paint heavier bodied; therefore, it may take longer to dry. In many areas of the United States, the amount of VOC expressed in pounds of VOC per gallon is restricted.

Imperial Power in Stone: Palaces, Villas & Mausoleums of Late Roman Emperors

Portraiture, coinage, and architecture were the most pervasive tangible means by which the emperor could proclaim to the world his legitimacy, his power, and his virtue. Of the three media, only architecture could establish the actual environment surrounding the increasingly sacrosanct figure of the head of state. This environment was made up of three principal settings, each with its roots in the past: the palace, where the emperor presented himself to the court ceremonially, the hippodrome, which, by the fourth century, had become firmly established as the principal locus for the emperor's appearances to the masses, and the imperial mausoleum, where the ruler perpetuated his presence after death.

A palace was erected wherever the emperor established an official residence. For almost three centuries the original palace on the Palatine Hill in Rome sufficed. But, with Diocletian's decentralization of imperial administration beginning in 286, palaces proliferated in Trier, Milan, Thessalonike, Nicomedia, Antioch, and other cities of the empire. With the restoration of sole rule by Constantine and the founding of Constantinople, all subsequent palace buildings were concentrated in the new capital. Constantine's first palace was successively rebuilt and enlarged over the centuries to form an entire quarter of the city.

Each late Roman palace contained a number of rooms for everyday functions—private apartments, a secretariat, quarters for staff and guards—as well as large state dining rooms and at least one, and often many more, halls for ceremonial appearances. A Christian emperor, moreover, required a chapel within the palace compound for his private devotions.

The Aula Palatina at Trier (no. 102), built by Constantine, is only one of the audience halls sufficiently well preserved to convey something of its original impressiveness. Preceded by a forecourt and a vestibule, the hall appeared starkly simple from the outside. Most of the decoration was reserved for the interior. While the interior walls of the first Roman palace were articulated with niches, pilasters, and projecting tabernacles, the walls at Trier were smooth, originally covered with marble sheathing and decorative stucco. This glowing space, illuminated by huge, glazed windows, was focused on the large apse at the far end, where Constantine presumably appeared in solemn majesty. Under the effect of Persian court ceremony, his audience was conducted with liturgical pomp and, on occasion, with recitals of panegyrics—rhetorical monstrosities of flattery favored in the late Roman world.

When not conducting state affairs in the capital or on campaign, the ruler often repaired to a villa where he could enjoy the royal pastime of hunting. Many of the imperial villas of earlier times continued in use in the late Roman period; a modest alteration of probably Constantinian date was even made to a portion of Hadrian's villa near Tivoli. Two interesting new country seats were built early in the fourth century: that at Split (the ancient Spalato) on the Adriatic coast of Dalmatia (no. 104), erected for Diocletian's use after his retirement in 305; and that at Piazza Armerina in the interior of Sicily (no. 105), identified by some archaeologists as the villa of Diocletian's colleague Maximian or of Maximian's son Maxentius. The two could not be more different, no doubt at least partly because the occupants and locations were different. Piazza Armerina is more in the tradition of earlier deluxe villas in its informal sprawl over a rolling terrain, although its constituent suites—each of which reflects a different aspect of villa life—are not as integrated with the landscape nor as open to it as in earlier villas. That the shaping of interior space was the late Roman architect's chief concern is nowhere better illustrated than at Piazza Armerina, and nowhere is it more emphatic than in the villa's plan, which, unlike the plan of other Roman villas, looks like an architect's space diagram.

In contrast to Piazza Armerina's haphazard exterior, Split's bastioned rectangular wall seems so redoubtable as to dissociate the compound from the traditional category of seaside villa. Less elaborate villas, and even farmhouses in areas subject to sudden alien, or—increasingly—domestic, incursions, were being fortified in the fourth century. The elaborately formal character of Diocletian's retirement seat, however, must ultimately have derived from the emperor emeritus' desire to perpetuate his imperial dignity. The internal organization at Split may derive from the Roman ceremonial military headquarters like that built at Palmyra by one of his lieutenants. If so, it is evidence of the interplay of civil and military planning in a militarized state.

Diocletian's monumental mausoleum, which rises to the left of the principal entrance to the imperial apartments, is one of Split's most notable elements. Royal tombs had been leading architectural vehicles of authority in many earlier cultures. Members of the imperial families from Augustus through the early third century were buried in dynastic tombs, most conspicuously the great Augustan tumulus and the cylindrical mausoleum built by Hadrian, both of which still stand in Rome. With the collapse of the dynastic principle of succession in the third century, this practice died out, and, in the chaos of crisis, some unfortunate emperors received no burial at all. When Diocletian established the short-lived policy of succession by ability and not by birth, a dynastic tomb had no value, and he erected a mausoleum for his wife and himself alone. The form he selected, a rotunda, first appeared in the suburbs of Rome in the third century as tombs of now- anonymous persons of great wealth. It was Diocletian, apparently, who raised the funerary rotunda to imperial rank, and it immediately became the standard form for royal mausolea. Typical of the diversity of stylistic expression in the period, the late Roman imperial mausolea differ as widely as did the villas at Piazza Armerina and Split.

Diocletian's mausoleum is centralized in form and has a domical roof, internally constructed of a crystalline octagon of cut stone preceded by a classical, pedimented porch. The niched, cylindrical surface of the inner wall is overlaid with the orders in two stories. The only light is admitted through the front door. Its plan may resemble those of Roman mausolea but its superstructure and its articulation owe much to the East.

The Rotunda of Galerius at Thessalonike (no. 107) is thought by most scholars to have been intended as his mausoleum. It, too, was erected in the palace quarter, but its walls, cylindrical internally and externally, are built of mortared rubble faced with bricks and small stones, the local substitute for Roman concrete. Its dome, in contrast to those in contemporary Rome, is built of solid brick in a technique native to Asia Minor. Unlike Diocletian's mausoleum, the interior of the rotunda at Thessalonike was articulated in a two-storied applique of marble architectural “wallpaper." The only plastic elements were small tabernacles at the bases of the great piers, whose size drew attention to the dominant two-dimensionality of the decor. With this feature, combined with the abundant windows, the Galerian rotunda resembled something like a circular version of Constantine's Aula Palatina.

When the body of Constantine, after what proved to be a provisional burial in the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople, was placed by his son in a great mausoleum adjacent to the church, the form of the sepulcher was a rotunda. It became the place of burial for subsequent late Roman emperors and in the first half of the fourth century, rotundas were erected under imperial patronage in the Holy Land over the sites of Christ's Birth and of his Resurrection. So potent was the form, that the Gothic king Theodoric, the de facto ruler of Italy in the early sixth century, erected as his tomb in Ravenna an octagon covered with a dome cut from a single, enormous block of stone (no. 109). Alfred Frazer. Bibliography: Form, 1959; Frazer, 1966; Swoboda, 1969; Boethius and Ward-Perkins, 1970; J. and T. Marasovic, 1970; Krautheimer, 1975.

Date added: 2025-08-01; views: 252;