Science Preserved: Why Illustrated Scientific Manuscripts Outlasted Literature in Late Antiquity

Science and Poetry. Rrhaps the most consequential innovation of Late Antique and Early Christian art was the codex form for the book, with its many folded smooth parchment leaves and ambitious miniature paintings. The traditional papyrus roll, like the romance papyrus in Paris (no. 222) or the Heracles poem in London (no. 205), already had diagrams and small pictures of modest quality. Yet the new medium attracted artists like those who, around 400, illustrated the Vatican Vergil (nos. 203, 224) and the Quedlinburg Itala (no. 424), artists who could compete with fresco painters and mosaicists and began to influence them, as they were in turn influenced by them. In contrast to these older branches of painting, book illumination developed two distinguishing characteristics: first, as a result of the greater intimacy of the illustrations with the written word, the illuminations more precisely illustrated the text and became more fixed in their iconography; second, because of the greater amount of space available, the scenes multiplied and developed the narrative mode, whereby one episode would be illustrated in many scenes in quick succession, so that the eye could glide from one to the other.

The impact of the illustrated book on later representational art after the first peak of book production in the fourth century must have been tremendous, but this is difficult to imagine today; because of the perishability of their material, natural wear, and often willful destruction, comparatively few illustrated codices have survived. That among the preserved illustrated classical texts the scientific ones outnumber the literary is due largely to their acceptability, on ideological grounds, to Christians, who highly esteemed such books for their practical applications. From the books still extant one point becomes clear— and this is most typical of classical civilization: the same splendid decoration and high standards of quality were lavished on scientific and literary texts alike.

The most luxuriously illustrated codex that has survived is the Dioscurides herbal in the Vienna Library (no. 179), which was written for an imperial princess in the sixth century in Constantinople. A whole set of panellike frontispieces precedes the text with its hundreds of full-page plant pictures of painstaking exactitude as well as of handsome design and coloration. We still can grasp the great impact this manuscript had on subsequent centuries through a seventh-century copy in Naples (no. 180) and a tenth-century copy in the Morgan Library, likewise the product of an imperial scriptorium (no. 181).

The same high artistic standards were also applied to zoological treatises, some of which are appended to the same Vienna Dioscurides manuscript, one on poisonous serpents whose bites are fatal (cf. the Nicander manuscript in Paris, no. 226) and another one on birds. Where birds of great variety are depicted on floor mosaics, the mosaicists apparently consulted such a treatise for scientific accuracy. Similarly, where we find a very naturalistic rendering of many diverse species of fishes on floor mosaics from Tunisia (no. 184) and Syria, especially Antioch, it is hardly to be assumed that the artist went to the fish market to sketch, but rather consulted a treatise on fishes, such as a cookbook. In addition to mosaics, sumptuous textiles (nos. 182, 183), fine glass (no. 185), and other media testify to the wide dissemination of this kind of scientific literature.

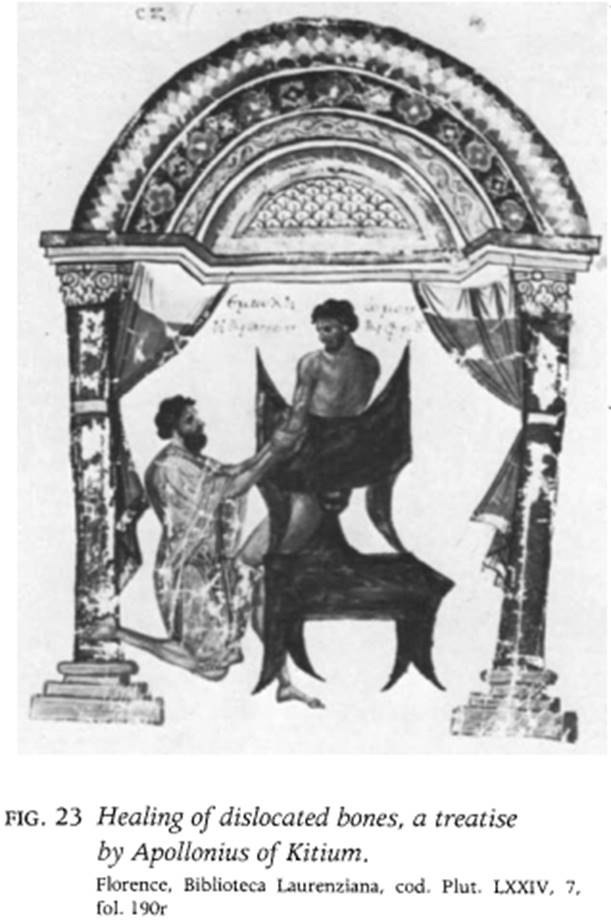

The tenth-century Dioscurides (no. 181) proves that medieval copies of scientific illustrations from late antiquity could be quite exact. Other medieval scientific manuscripts can also be assumed to reflect a high degree of faithfulness to Late Antique models. It is only through such copies of illustrated medical treatises that we learn of Late Antique compendia in codex form and their archetypes that may possibly date to the period of the papyrus roll. Examples of Hippocratic healing methods are preserved in a tenthcentury treatise by Apollonius of Kitium, which demonstrates the setting of dislocated bones (fig. 23), and a medieval Latin handbook on midwifery by Soranos of Ephesus, which pictures the different positions of the embryo in the uterus (no. 187).

Even such a technical subject as surveying was deemed worthy of luxurious illustration (no. 188), not to mention numerous specialized engineering treatises on mechanics, automata, and war engines (no. 189), like those of Heron of Alexandria and Apollodorus of Damascus and many others, of which a comparatively large number of copies has survived. Some didactic treatises touch the borderline between science and literature. Most popular were the socalled Aratea, named after the astronomer Aratus, whose constellation pictures continued to be copied into the Renaissance, when illuminations were replaced by woodcuts and engravings. A Carolingian manuscript in Leiden (no. 190) has copied a fourth-century model so faithfully that, artistically, it could almost be mistaken for a Late Antique product.

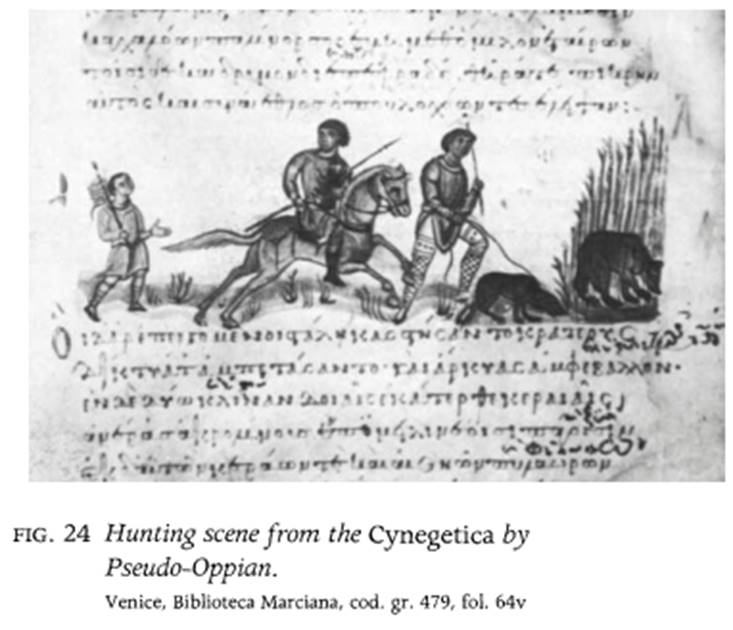

To judge from their wide reflections in other media, hunting treatises must have enjoyed particular popularity. Whereas a profusely illustrated manuscript of Pseudo-Oppian from the eleventh century in Venice displays an extraordinary variety of hunting techniques (fig. 24), selected hunting scenes in late classical mosaics and silverwork (no. 251) demonstrate once more how valuable the miniature cycles were as a repository of iconography.

Of all the didactic poems of late antiquity, the one with the greatest impact on the Middle Ages was the Physio logus, because of its moralizing applications. A Carolingian copy in Bern still shows the flavor of the painterly late classical style (no. 192).

Since archaic times Greek art drew much of its inspiration for scenic representations from mythology as it was transmitted orally and through epic poetry. From the high classical period on, additional inspiration came from dramatic poetry and later from prose. But it was only in the book, first the roll and then the codex, that, by application of the narrative method, the number of mythological scenes was vastly increased.

The literary text most often copied in antiquity— and one would assume also its illustration—was Homer's Iliad, and thus it is hardly an accident that of only this Greek epic has a fragmentary miniature cycle come down to us, now in Milan (no. 193). That such miniatures had previously existed in papyrus rolls is proven by a drawing in Munich (no. 194), whose subject, Briseis being led away from Achilles, attracted, among other artists, metalworkers, who incised it on various objects in bronze (nos. 195, 196). Scenes from the Iliad occur also on a silver plate (no. 197) and a textile (no. 198), though dependence on miniatures must in such cases not always be direct. It must be merely accidental that no illustrated Odyssey survived, but its existence can again be demonstrated by stray scenes in other media, like the popular story of Odysseus and the Sirens, known from numerous sarcophagi and from a bronze (no. 199). Nor were epic illustrations confined to the Homeric poems. The miniaturelike paintings on the wooden shields from Dura (nos. 200, 201) tell stories that, like the battle against the Amazons, come from the Aithiopis of Arktinos or, like the Trojan Horse, from the Little Iliad of Lesches; the latter is also the source for the silver plate in Leningrad with Ajax and Odysseus contesting the weapons of Achilles (no. 202).

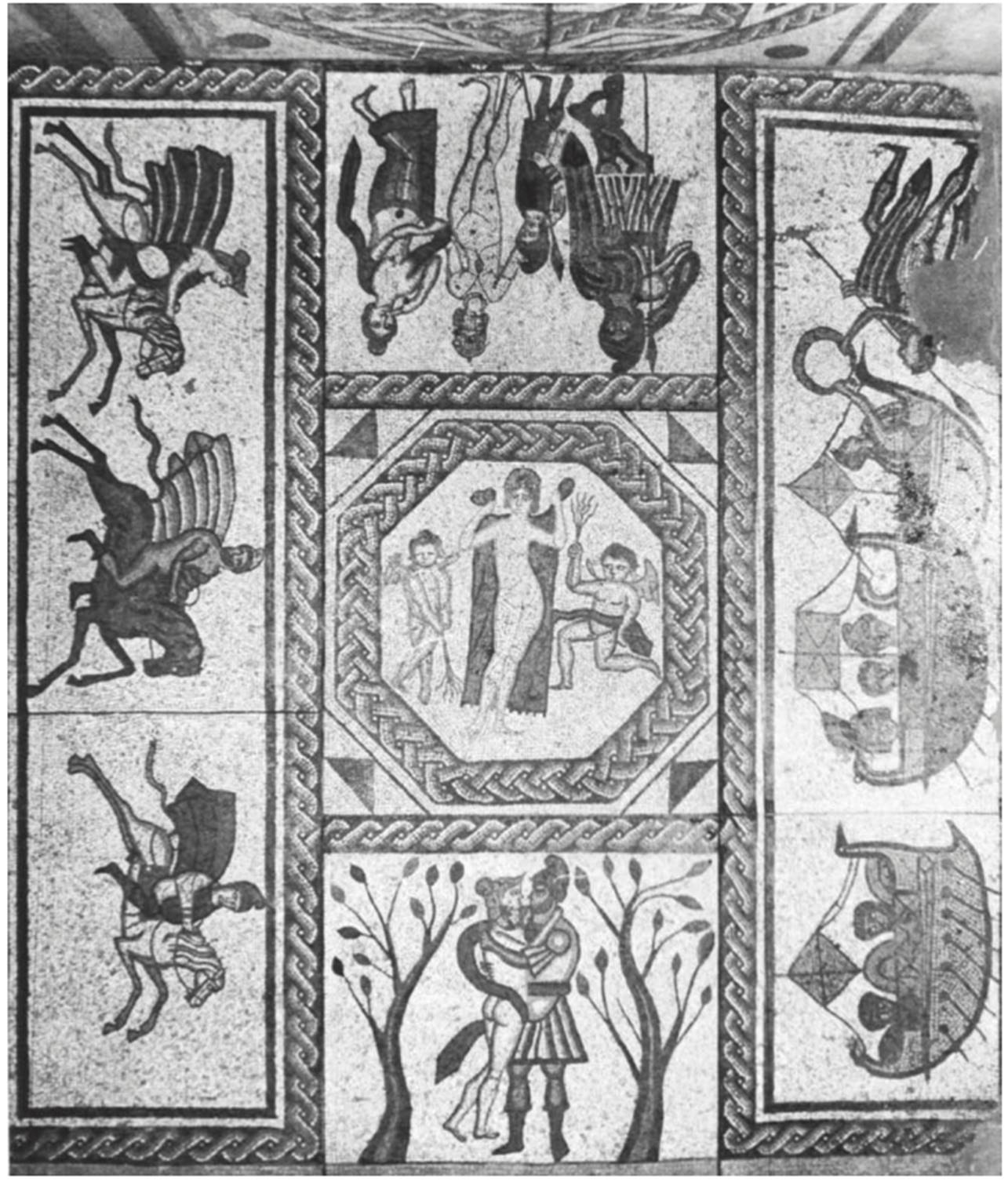

The greatest Latin epic poem, Vergil's Aeneid, luckily survives in two splendidly illustrated manuscripts, one in the refined style of Rome (no. 203) and the other in the rough style of some unknown province (no. 204). They are so totally different from each other that we must assume that more than one start was made with Aeneid illustration. The fourth-century mosaic found at Low Ham in Somerset, England (fig. 25), attests that the illustrated Aeneid spread throughout the Roman Empire.

Fig. 25. Mosaic with scenes from the Aeneid. Low Наш, Somerset, Englan

There also existed poems with illustrations of popular heroes, foremost Heracles and Achilles, who, as personifications of virtues, had survived in the Christian culture of later centuries. Representations of the deeds of Heracles were, of course, as old as Greek art itself, but it was not until the invention of book illumination that each of the twelve labors expanded into narrative cycles. A papyrus in London is the best witness of this expansion (no. 205). No illustrated Achilleis has survived, but its widespread impact on many media can be demonstrated by the continuous narrative friezes on a marble plaque (no. 207), silver (no. 208), terracotta (no. 209) and bronze plates (no. 210), an ivory pyxis (no. 211), and many others. We shall never know how many texts existed or how many of these had pictures, and it is no longer possible to determine with certainty the textual basis for many single pictures of epic character (nos. 214, 215).

The most widely read dramatic poet in antiquity was Euripides. Illustrations of his tragedies are best reflected in an incised bronze plate that has several scenes from the Bacchae as well as a depiction of the masks (no. 216). Scenes from Phaedra appear on a Byzantine silver plate (no. 217), as well as on a mosaic from Antioch (fig. 26), and one from Iphigenia in such an unlikely medium as textile (no. 218). A fresco depicting a scene from the Alcestis (no. 219) occupies the catacomb of the Via Latina in Rome, which has predominantly Christian scenes (nos. 419, 423), providing the best evidence of the coexistence of classical and Christian imagery in funerary art.

Fig. 26. Mosaic with Hippolytus and Phaedra. Antioch

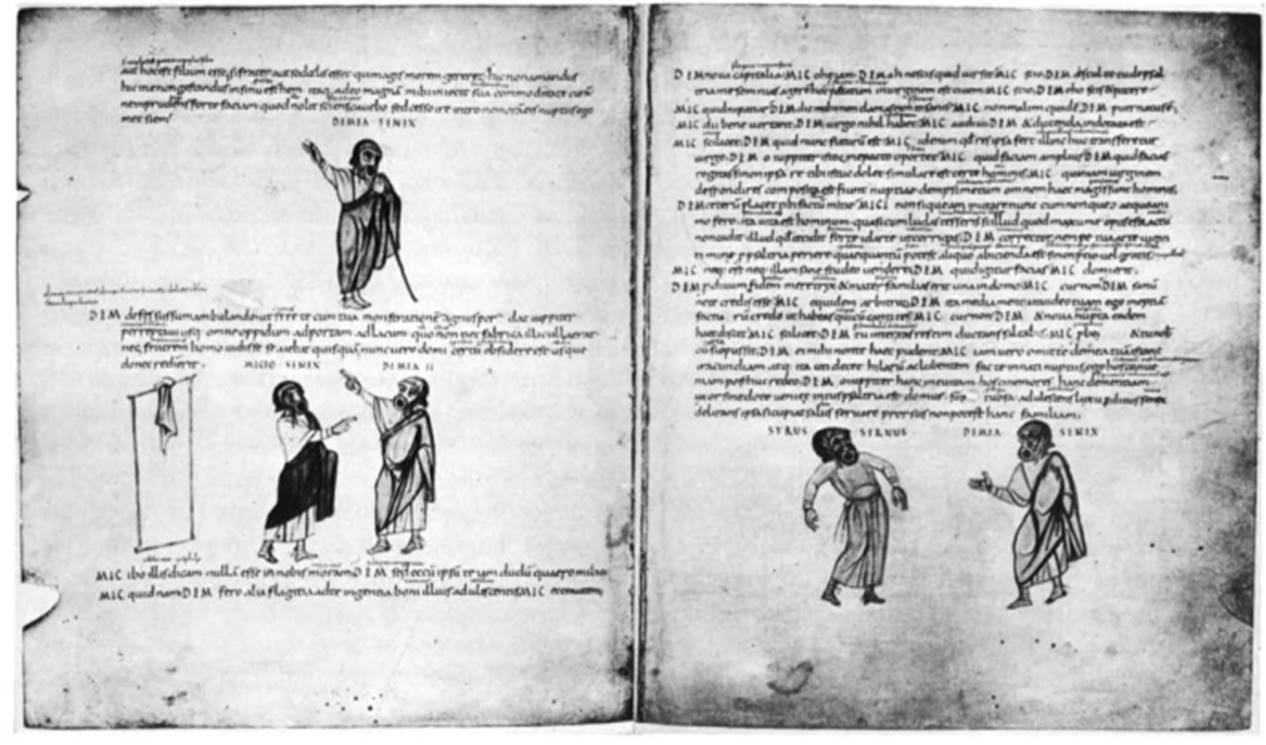

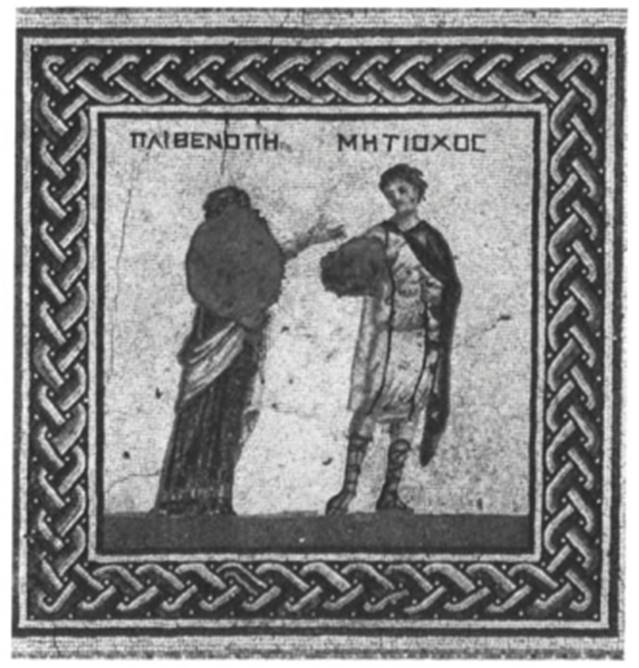

By far the most popular of the comic poets was Menander, and illustrations of quite a number of his comedies in mosaic have recently come to light on the island of Mytilene (no. 221). Menander's comedies served as models for those of Terence in the Latin West and the faithful copying of illustrated Terence manuscripts as late as the Carolingian period (fig. 27), and even thereafter is a strong indication of the tenacious survival in the Christian world of comic poetry, though derided by some Church fathers. Much pleasure must have been derived from reading romances with illustrations (no. 222), and it must have been a learned patron who had a floor mosaic in his house depicting a scene from the romance of Metiochos and Parthenope (fig. 28). The dense, comic- strip-like illustration of such romances is still reflected in a medieval copy of the romance History of Apollonius, King of Tyre (no. 223).

Fig. 27. Scenes from the Adelphoe of Terence. Vatican Library, cod. lat. 3868, fols. 60v-61r

Fig. 28. Mosaic with Metiochos and Parthenope, from Antioch. Worcester, Massachusetts, Worcester Art Museum

Of particular importance with respect to its acceptance by the Christians is bucolic poetry, which started with Theocritus' Idylls and soon sprouted into a popular branch of literature in the Hellenistic and Roman periods. The illustrations of the Georgies and Eclogues of Vergil in the two Vatican manuscripts (nos. 224, 225) are our best examples of miniature cycles that depend on the Greek tradition, like that reflected in some miniatures in the Nicander manuscript (no. 226). Pictures of the happy shepherd's life abound in every conceivable medium; four textile roundels (nos. 227-230) represent the closest dependence on a miniature cycle. Subjects of this kind on sumptuous silver plates (nos. 231, 232) and in gold glass (no. 233) no doubt delighted the cultivated art collector, Christian and pagan alike. Bucolic and idyllic scenes abound on sarcophagi (no. 237), where it is not always clear whether the representations are pagan or Christian. The Christians so liked the spirit of bucolic life and art that a dining party of hunters or shepherds might be turned into a commemorative funerary banquet scene on a sarcophagus (no. 236) or in catacomb paintings. It is not only by chance that the earliest widespread image of Christ himself, that of the Good Shepherd (nos. 462, 463), emerged from this iconographic milieu.

The high regard held for poets, epic and dramatic alike, in the Greco-Roman culture is reflected in the large number of their statues, busts, and heads in marble and bronze. Late Antique art, however, following the general trend of the time, shifted more and more to the two-dimensional arts—frescoes, mosaics, and especially miniatures. While frescoes vanish rather easily, mosaics are somewhat more durable. The bust of Menander (no. 221) and the seated poet watching an actor (no. 239) are characteristic examples. The author, inspired by a muse or personification, was a suitable subject for the frontispiece of the author's work, as in the case of the Dioscurides no. 179. The popular subject of the writer and the inspiring muse occurs in a great many variants: a pair of ivories in the Louvre (no. 242) shows muses inspiring authors, and each group has the quality of a frontispiece miniature.

The individual muse may even become the center of a composition (no. 241), or the nine muses may be lined up independent of any author, as in the Moscow vase (no. 244), or led by Apollo, the leader of the muses, as in no. 243, where they are associated with Dionysiac figures from a play. Often found on sarcophagi is a figure of the deceased, who aspired to be appreciated as a litteratus, surrounded by the muses (no. 240). Here, it is by no means certain that the deceased was a pagan. Any educated Christian could adopt the motif of the inspiring muses without conflict of conscience. This motif actually became so attractive to the Christians that the four evangelists were frequently depicted writing their Gospels under inspiration, as in the earliest Greek evangelist portrait in existence, the Mark from the Rossano Gospels (no. 443).

The inspiring figure is probably, in this case, no longer a muse, but more likely is a personification of Wisdom; however, since Sophia herself is the creation of a classical idea, the fact remains that Christianity is indebted for one of its most consequential artistic creations to the classical tradition. This indebtedness extends even further to the creation of the evangelist pictures themselves, which were not actual historical portraits, but such undisguised adaptations of classical poets and philosophers that most of the models can still be identified. In such creations classical imagery lives on in the Christian world. Kurt Weitzmann.

Date added: 2025-08-31; views: 147;