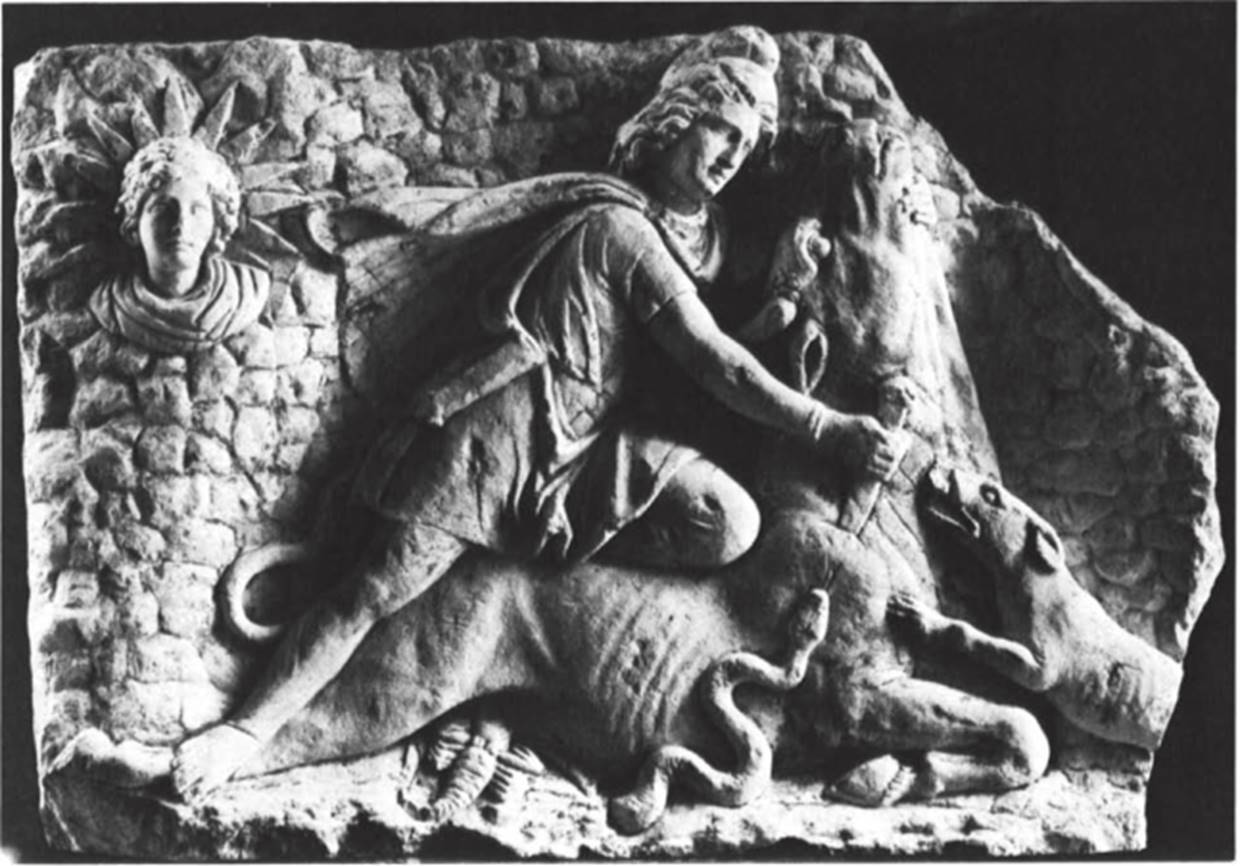

Relief with Mithras slaying the bull. Rome, 2nd half 2nd century. Limestone

Originally a rectangular block, the relief now has a major section from the upper right corner and smaller pieces from the right edge and lower corner broken off. The surface of this grainy fabric has incidental cracks and gouges but is on the whole well preserved. The main scene cuts into the remains of a shallow relief preserved on the right side, indicating secondary use of the stone.

In the rocky setting of a cave, Mithras, in tunic, pants, Phrygian cap, and barefoot, is shown victorious over his enemy, the world-bull, after a long struggle. Forcing the bull to the ground as it loses strength, Mithras presses it down farther with his left knee, while stepping on its extended rear leg, pulls back the animal's head with his left hand under its chin, and plunges a dagger into its neck—the empty scabbard at his waist. A dog and a snake jump at the mortal wound to drink the vital and potent blood; a scorpion attacks the testicles, trying to stem the bull's strength. A youthful bust of Helios, with radiate halo and draped mantle, is behind Mithras' fluttering cape. A bust of Luna originally balanced Helios; a trace of the crescent on which her bust appeared is discernible along the edge of the break.

The bull-slaying episode, the most significant of Mithras' exploits, was also the one most frequently represented on the cult images in sanctuaries dedicated to him. In accomplishing the ritual sacrifice of the bull, symbol of all generative forces (the astrological Taurus marking the beginning of spring), Mithras releases for mankind its life- renewing blood. Within the cave, dark analogue to the open sky, the drama of death and resurrection (renewal of life) is acted out according to the directive from the superior sun god. The dog, sacred animal of the Persians and hunting companion of Mithras; the snake, symbol of the earth among the Greeks; and the scorpion, zodiacal symbol of autumn, the end of growth and a beneficent motif in some Near Eastern regions, point out the heterogeneous sources of Mithraism's iconography.

Such a variety of references reveals the accretions of theological speculation over wide spans of geography and time. Nonetheless, this cult relief is among the simplest of its kind. The dense, curly hair of Helios, the bland, smooth cutting, and the planar treatment of the faces suggest a date in the second half of the second century.

From the Via Praenestina in Rome, where it was reused as a doorstep. Bibliography: Gordon, 1974.

Date added: 2025-08-31; views: 146;