Oceans as Cultural Drivers: Trade, Inspiration, and the Enduring Role of Fisheries

Introduction. Culture comprises many elements, including beliefs, social norms, traditional customs, the arts, civic institutions, and collective achievements of people or societies, and people both shape culture and are shaped by it. In considering why oceans and seas matter in world culture, it is essential to realize that before mechanical ground transportation and aviation in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, ships and boats were usually the most efficient means of transportation—when they were not the only ones. Thus, the opening of sea routes invariably resulted in cultural transformation, sometimes immediate, other times only in the long term.

The role of oceans and seas in world culture can be thought of in three distinct ways. The world’s myriad fisheries are often overlooked in discussions of the seas and oceans in culture and history because, for most people, fishing has traditionally been a subsistence activity about which little was written or recorded. Because most fishing grounds are generally located no more than a day or two’s sail from home, the cultural impact has seemed negligible. But it is likely that people first set out on the water not to trade, but to hunt for fish, birds, and other animals, as reflected in some of the world’s oldest representational art.

Oceans and seas are also vectors of culture, for everything from language and religion to food and dress, to political, economic, and legal institutions. Before a little more than a century ago, everything that today travels between continents by airplane, telephone, or Internet had to be carried by maritime trade. (And “cloud” computing notwithstanding, most intercontinental Internet communication is via undersea cables laid by ships.) Some of this we know about from written accounts and records, but we can also trace patterns of maritime exchange and travel through archaeological finds, as well as by tracing the diffusion of language, religion, and other cultural norms, which is why such diverse disciplines as linguistics, paleobotany, and ethnography are so vital to the work of maritime historians.

The third prong of the trident concerns the role of seas and oceans as sources of artistic and spiritual inspiration. These include mythic explanations of the origins of things, like the flood stories from the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh and its later expressions, to pictorial renderings of the sea in its moods and as a geopolitical or environmental space.

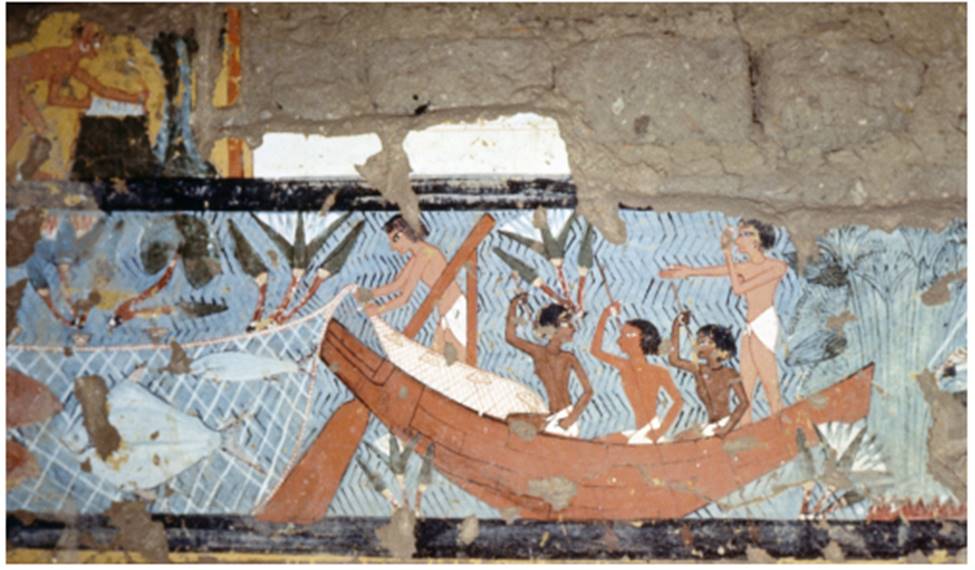

Fisheries. Among the oldest depictions of boats are 6,000-year-old petroglyphs in northern Norway, where people rendered a variety of waterborne activities on rocks. One shows people in a boat hunting reindeer, which are consummate swimmers, and easier to kill when most of their body mass is submerged than when on land. Contemporary with these are images of hunters pursuing hippopotami in boats found in the Tassili n'Ajjer in southeastern Algeria. More orthodox scenes of fishing and hunting survive from Egypt starting in the Old Kingdom (c. 2700-2055 BCE) and in Minoan frescoes from the island of Akrotiri, or Thera (c. 1500 BCE).

The fish is an important symbol in most religious traditions, one reason being that the multitude of eggs they lay is considered a sign of abundance. Salmon are revered by people in an arc that spans the northern rim of the Pacific from the Japanese island of Hokkaido and eastern Siberia to Alaska and the Pacific Northwest. In Buddhism, a pair of fish represents the fearlessness with which the Buddha swims in the dread cycle of samsara, or birth, death, and rebirth. The fish has also been strongly identified with Christianity since the religion’s earliest days. Christ called his first four disciples from their boats to become “fishers of men,” and the Gospels record two miracles in which Christ fed thousands of followers with only a handful of loaves and two (or a few) fishes. The Greek word for fish, ichthys, is also an acrostic of lesous Christos Theou Yios 5oter, meaning “Jesus Christ, Son of God.”

Despite their ubiquity, written descriptions of local fisheries are few. Two modern works that capture the often-closed world of these sheltered communities are Yukio Mishima’s The Sound of Waves (1954) and Brazilian Jose Sarney’s magic realist novel Master and the Sea (1963). The former depicts the life of Japanese ama, or women divers, whose hunting for abalone and sea urchins at depths of up to 10 meters was first recorded in poems dating from the eighth century. The women divers of Jeju Island (the Jeju haenyeo) in Korea, whose involvement in the trade dates to the seventeenth century, are listed in UNESCO’s register of the world’s Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Although most people fish in their home waters, long-distance fisheries have played a major role in world history. In Polynesian mythology, fishing is thought to account for the very existence of many islands and for humans’ discovery of places from Hawai‘i to New Zealand. In one tradition, fishermen from Hawaiki (Tahiti) came across New Zealand while chasing an octopus that was stealing their bait. More recently, the search for cod drew Spanish, Portuguese, and English across the North Atlantic to Iceland, Newfoundland, and ultimately the Gulf of Maine, whose fisheries helped sustain the more corporate and better- known efforts at colonialization at Jamestown, Virginia, and Plymouth, Massachusetts, in the early seventeenth century. Negotiating the treaty that ended the American Revolution, John Adams was adamant about protecting American fishermen’s “Right to take Fish” on the Grand Banks and preserving their “liberty” to dry their catch “in any of the unsettled bays, harbors, and creeks of Nova Scotia, Magdalen Islands, and Labrador” (Paris Peace Treaty 1783: art. 3). His home state of Massachusetts (the easternmost part of which is Cape Cod) was so dependent on fish that the general court hung “the representation of a Cod Fish in the room where the House sit, as a memorial of the importance of the Cod-Fishery to the welfare of this Commonwealth” (Roberts, Gallivan, and Irwin 1895: 13).

Details from a painting found in an Egyptian tomb from the nineteenth Dynasty (1292-1189 BCE) in Deir el-Medina, depicting Egyptian fishermen casting nets (Werner Forman/Universal Images Group/Getty Images)

At around the same time, whaling was becoming a deep-sea venture. Although European whalers had sailed long distances to find whales for centuries, they rendered whale blubber into oil at shore stations. New technologies enabled them to do this aboard ship in midocean, and by the late 1780s, whalers were beginning to venture into the Pacific on voyages that routinely lasted three years or longer. This is how long the Pequod is at sea before being stoved in and sunk in Herman Melville’s magisterial novel Moby-Dick; or, The Whale (1851). The whaling industry peaked later in the decade, and opposition to the continued practice of whaling has been a feature of the environmental movement since a moratorium on commercial whaling was instituted in 1985-1986. A handful of nations continue to practice whaling in defiance of international opinion, and some aboriginal peoples in the Northern Pacific and Arctic, Greenland, and the Caribbean are entitled to limited catches.

Over the past century and a half, the advent of mechanical propulsion and winches, synthetic fibers, and remote sensing devices like sonar, spotter planes, and drones has enabled fishing vessels to operate at ever greater distances from home, which has led to overfishing and put a spotlight on the fragility of a resource once considered limitless. This has been exacerbated by the advent of refrigerated shipping, which enables lobsters to be flown from Maine to China or tuna from Australia to Japan, for instance, within hours of their being landed, thus creating a demand for certain fish where none existed before.

Date added: 2025-10-14; views: 175;