The Ship as Metaphor: How Vessels Shaped Statecraft, Culture, and Imagination

The Ship as Metaphor. When it comes to gauging the strength of a culture’s identification with maritime enterprise, there are few better indicators than the ease with which it employs the metaphor of the ship of state. This is an ancient conceit, the oldest written reference to which, the Egyptian “Tale of the Eloquent Peasant,” dates to 2100 BCE. In this story, a peasant named Khunanup has been robbed and appeals to the pharaoh for justice. Khunanup repeatedly resorts to the imagery of the ship: “Behold, I am on a voyage without a boat” (Simpson 2003: 33), he says at one point. Later he chastises the pharaoh’s high steward for creating a situation that is “Like a ship on which there is no captain” (Simpson 2003: 36).

The same imagery recurs in classical Greek and Latin literature—the verb “to govern” comes from the Greek word meaning “to steer,” by way of the Latin gubernare, which means both “to steer” and “to govern”—but this is not surprising in light of the close maritime connections that bound the people of the Mediterranean. Nor is the metaphor unique to the West. The people of the Perak Sultanate, on Sumatra, identified their state as a ship, “with the ruler as her captain (nakhoda) and some of the ministers as members of the crew,” including a mate, helmsmen, lead oarsmen, and “the person who bales the ship if she leaks, i.e., who removes any danger threatening the country” (Manguin 2005: 6-7). Similarly, Maori today trace their descent from members of the crews of the waka (canoes) in which their ancestors arrived in New Zealand 700 years ago, and the waka represents an important unit of Maori group affiliation.

States that relied deeply on the sea and maritime power have gone to great lengths to adorn their ships, which could function as instruments of propaganda. Starting in the eleventh century, the Venetians developed an ever more elaborate ceremony during which the doge, his retainers, members of the clergy, and ambassadors to Venice set out in a resplendent state barge called the Bucintoro to enact a spiritual joining of the city-state and the Adriatic. Declaring “We wed thee, Adriatic, as a sign of our true and perpetual dominion,” the doge dropped a gold ring into the sea, and in so doing, proclaimed Venice’s exclusive mastery over the Adriatic (Senior 1929: 135).

The ship of state as an instrument of propaganda reached its apogee in seventeenth- century Europe, when the general feeling was, as Louis XlV’s minister of finance wrote, “Nothing can be more impressive, nor more likely to exalt the majesty of the King, than that his ships should have more magnificent ornamentation than has ever before been seen at sea” (Paine 1997: 569). The greatest exemplar of the form is the Swedish warship Vasa, which sank on its maiden voyage in 1628 and was raised from the seabed more or less intact 350 years later. The ship’s more than 1,000 wooden sculptures comprise a complex iconography intended to show the legitimacy and power of the House of Vasa, including a magnificent stern decoration showing the House of Vasa’s coat of arms, a series of figures from the Old Testament Book of Judges, a representation of Gideon’s victory over the Midianites, and an image of Hercules. Lining the bulkhead forward are two rows of Roman emperors, and the bowsprit features a forward-leaping gilded lion. Other ships of the era boasted comparable symbolic imagery and names that reflected the sovereign ruler’s ambition. England’s Charles I ordered the Sovereign of the Seas, the name of which bolstered the king’s intent to reassert England’s ancient, if fanciful, title to the waters around the British Isles.

At the time, there was a renewed debate over the right to territorial seas. In Mare Liberum or “Free Sea” (1609), Hugo Grotius argued “it is lawful for any nation to go to any other and to trade with it” (Grotius 2004: 11), and that claims to a monopoly of trade on the basis of a papal grant, territorial possession, or custom were groundless. Now recognized as a cornerstone of international law, it was countered vigorously by John Selden’s Of the Dominion; or, Ownership of the Sea (1635), which argued that nations could exclude rivals from certain waters. Dedicating his work to Charles I—“The sea will also submit to him”—Selden delineated an absurdly expansive conception of the “sea-territory of the British Empire” (Thornton 2006: 112), which extended all the way to North America. Similar ideas are also evident in the work of writers like John Dryden, who, following an English victory over a Dutch fleet in 1666, wrote “all was Britain the wide ocean saw” (Paine 2010: 213).

The Ship as Vehicle. As an essential means by which people relate to the seas and oceans, ships have been central to the culture and identity of maritime people. If warships represented early modern rulers’ maritime ambitions, with the rise of the nation-state and national identity, ships began to embody the aspirations of the general public. This was especially true among Western powers from the mid-nineteenth to mid-twentieth centuries, when national rivalries found explicit expression in the construction of ever more powerful naval ships and ever faster and more lavish passenger ships. Mein Feld ist die Welt (“My Field Is the World”) proclaimed the motto of Germany’s Hamburg-American Line, whose passenger liners were among the proudest on the North Atlantic. At the same time, ships and even yachts came to reflect cultural norms and ideals for both good and ill. When in 1851 a syndicate sent the oceangoing racing schooner America across the Atlantic to challenge English yachts in English waters, newspaper publisher Horace Greeley wrote, “The eyes of the world are on you. You will be beaten, and the country will be abused. . . . If you go and are beaten, you had better not return” (Paine 1997: 21). The America did return, and with the prize known ever since as the America’s Cup.

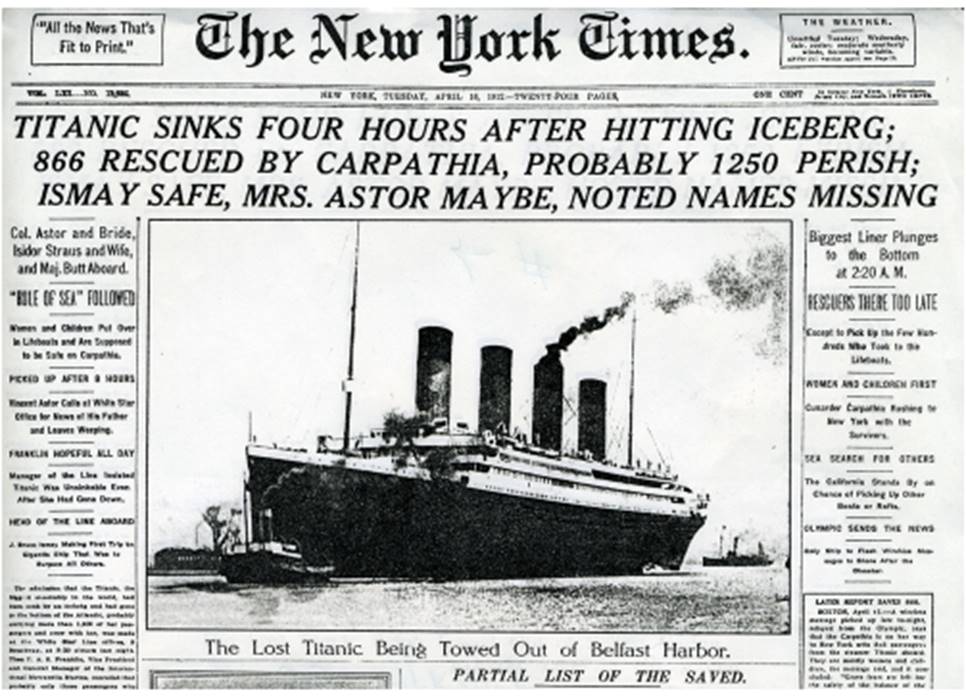

At the other end of the spectrum is the Titanic, which sank on her maiden voyage in 1912 with the loss of more than 1,500 lives, more than two-thirds of her passengers and crew. Thanks to the recently invented wireless telegraph, this was one of the first disasters of its kind to be broadcast in something close to real time, which gave it a previously unheard-of immediacy. This also helped disseminate competing narratives about what the loss of the Titanic symbolized. Foremost was the tripartite code of honor against which all survivors and victims were measured at the time: “Women and children first”; gentlemanly conduct—a function of both gender and class; and the superior behavior of Anglo-Saxons generally. The exemplars were wireless operator Jack Phillips and band leader Wallace Hartley, who remained at their posts until the ship sank, gratuitously selfless behavior that earned them the lion’s share of public acclaim. A minority view held that the loss of the ship was divine retribution for “those given to greed and pleasure in a world cursed by sin,” which overlooked the fact that only a quarter of the 710 third-class passengers survived. In the United States, the story was taken up by people on either side of the debate over women’s suffrage. Those against giving women the vote pleaded that the “gentlemanly behavior” on display provided adequate protection for women. Suffragists maintained that whereas captains of ships might step aside for women, “the captain of industry makes sure first of a comfortable living for himself” (Biel 1996: 104). They also argued that had women been involved in the Titanic’s design, building, or navigation, the ship might not have been lost. By the end of the twentieth century, Edwardian ideals and equal rights’ arguments had been eclipsed, and James Cameron’s movie Titanic (1997) focused popular imagination on the figure of Thomas Andrews, “the creator of a technological marvel destroyed by his own creation,” a fate that resonates in a world “increasingly dependent on technology and, at the same time, increasingly at its mercy” (Barczewski 2004: 144).

Although people have long conceptualized ships as symbolic and metaphorical entities, it was not until the 1960s that the French philosopher Michel Foucault articulated what made them so, when he described the ship as “a floating piece of space, a place without a place, that exists by itself, that is closed in on itself and at the same time is given over to the infinity of the sea” (Foucault 1986: 27), a site in which the norms of society “are simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted.” So, for example, ship captains are “masters under God,” with greater authority over their crew and passengers than virtually anyone of a similar station in life on land.

The ship as heterotopia, or “other place,” and the influence of the maritime world on the land took a curious turn with the coming of steam-powered ocean liners at the end of the nineteenth century. Because ships were the only way to cross any body of water broader than a river, shipping companies had something of a captive market. Yet, they could not rely exclusively on the immigrant trade and people who had to travel for business, for despite the fact that ships were becoming ever safer, being on a ship midway between two continents is something that many people instinctively fear. The solution for ship designers was “to convey the idea that one is not at sea, but on terra firma” (Brinnin 2000: 340). Gilded Age designers of ocean liner interiors took their inspiration from, among other land-based sources, seventeenth-, sixteenth-, and even fifteenth-century European manors, mansions, and castles. The result was incongruous, for although shipping companies vied to build the biggest, fastest, and most indestructible ships possible, they knew their passengers wanted interior spaces that were “as little like a ship as human imagination can do it” (Brinnin 2000[1971]: 392).

In 1925, the International Exposition of Modern Industrial and Decorative Arts took place in Paris. This gave us the term arts decoratifs, or art deco, though until the 1960s it was generally known as “ocean liner style” (Peter and Dawson 2009: 149). It first went to sea in 1927 in the Ile de France, whose designers opted for a sleek, streamlined look that promised efficiency, speed, and modernity. In a curious twist, the ocean liner’s style was adopted by architects and designers ashore so that buildings and their furnishings began to look like ships, rather than the other way around. This approach endured until ocean liners lost their passengers to jet planes. When passenger shipping revived in the 1980s, the ships were built almost exclusively for cruising, and they began to look like massive floating resorts, which they are, with a preponderance of amenities that would not be out of place ashore.

Notwithstanding the resonance of some isolated events, usually disasters, and the fact that vastly more people go to sea on cruise ships today than ever traveled on ocean liners, since the 1960s the cultural influence and relevance of the maritime world per se have receded from public view. As passenger shipping declined at the end of the 1950s, containerization and massive bulk carriers, especially oil tankers, were changing both the face and nature of commercial shipping. Containerization and automation forced shiphandling operations into bleak industrial lands far from the docks around which port cities like Amsterdam, New York, and Hong Kong originally grew. They have also decreased the size of ships’ crews and gangs of shoreside cargo handlers, who lent color and a sense of the exotic to seaports. In an unmistakable expression of “form follows function,” the new shipping has yielded a grimly utilitarian aesthetic, afloat and ashore, as so-called box ships began to expand the volume of goods traded worldwide and to promote consumer culture that migrated from city centers and downtowns to cavernous, windowless suburban box stores.

Thanks to these developments, the traditional expressions of maritime culture have all but disappeared, especially the ancient sailors’ arts of carving, knot work, and other handicrafts, as well as chanty singing and storytelling. The one sailors’ art that has blossomed in the same period is tattooing, which Western sailors learned from Pacific Islanders in the eighteenth century. But, for most people, tattooing is a passive art, something done to oneself rather than by oneself.

Artistic and Spiritual Inspiration. The profound cultural significance of the seas and oceans is clear from the fact that worldwide there are hundreds of deities, divinities, saints, and others associated with aquatic environments, related geographic and meteorological phenomena, and the people who depend on them. Not surprisingly, maritime technology and enterprise feature in some of the world’s oldest examples of representational art: petroglyphs of boats in Gobustan, Azerbaijan, overlooking the Caspian Sea, which date to 12000 BCE—8,000 years before the hunters of reindeer and hippopotami mentioned earlier. The importance attached to boats is evident from their place in religious rituals, especially burials, in Egypt, Northern Europe and the British Isles, East and Southeast Asia, and the Americas. And the sea itself features prominently in cultural belief systems. As rising sea levels threaten to drown the San Blas Islands off Panama’s Caribbean coast, some Kuna Yala elders refuse to move, seeing the rising tide as indicative of their community’s loss of “spiritual equilibrium” (White 2017: 272).

Foucault wrote that “the boat has not only been for our civilization, from the sixteenth century until the present, the great instrument of economic development . . . but has been simultaneously the greatest reserve of the imagination” (Foucault 1986: 27). Because they function as microcosms of the “real” world, writers and other artists can depict events aboard ships in ways that reflect situations on land without doing so explicitly. This accounts for the durability of the concept of the ship of state and the variety of meanings attached to episodes like the sinking of the Titanic or the mutiny on the Bounty.

Bligh’s peerless feat of open-boat navigation sailing to Timor notwithstanding, the focus of the Bounty story has always been on the mutiny and mutineers. From almost the moment of Bligh’s return to England, evaluations of his behavior and Christian’s motives have been viewed in terms of a struggle between authoritarianism and freedom. This schism is due in part to the fact that, as a recent historian has written, “It was Lieutenant Bligh’s ill luck to have his own great adventure coincide exactly with the dawn of this new [Romantic] era, which saw devotion to a code of duty and established authority as less honorable than the celebration of individual passions and liberty” (Alexander 2003: 345).

Famous front page of The New York Times from April 16, 1912, reporting on the sinking of the Titanic (Library of Congress)

For most of recorded history, artists have focused on things of and in the sea and people’s relationships with them. A change occurred in the early modern period as oceancrossing sailors realized an oceanic immensity previously assumed in names like Sea of Darkness, as the Atlantic was known, and place names like Land’s End. While artistic renderings of ships grew more exact, their depictions of untamed seas became more vivid and energetic, with the heightened sense of realism confidently suggesting that ships were equal to whatever challenge nature posed.

This was the backdrop to the emergence of the Romantic movement in art, which reveled in atmospheric painting animated by the immediacy of personal experience. It found expression on both sides of the Atlantic, notably the work of J. M. W Turner in England and the Hudson River School in the United States. At heart, a response to industrialization and urbanization, Romanticism extolled the individual and the natural world, from which people were increasingly alienated, and it had a powerful analog in literature. As WH. Auden wrote, the hallmarks of Romanticism were an urge “to leave the land and the city” and a belief that “the sea is the real situation and the voyage is the true condition of man . . . where the decisive events, the moment of eternal choice, of temptation, fall, and redemption occur” (Auden 1951: 3). Exemplars of Romanticism in maritime literature include Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798), Lord Byron’s The Island, or Christian and His Comrades (1823), Melville’s Moby-Dick (1851), and Victor Hugo’s The Toilers of the Sea (1866).

Carrying an Albatross around One’s Neck. An albatross can cut through the sky, gliding, with barely a flap of its wings. A soaring albatross would have an almost hypnotizing effect on sailors, who believed that this bird would guide the crew and passengers to safety. The ocean bird came to be seen as a symbol of good luck among mariners and explorers, and to kill this majestic creature meant to tempt fate. It is precisely the killing of an albatross that inspired Samuel Taylor Coleridge to pen his famous poem, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” first published in the late eighteenth century. The poem’s tragic sailor kills an albatross with his crossbow and, as tragedy befalls the ship and crew, is forced to wear the bird’s carcass around his neck to identify him as the culprit of the curse. Although the sailor, unlike most of the crew, survives the voyage, he is forced to wander the Earth telling others about his misdeed. The cultural reference “to wear an albatross around one’s neck” thus signifies the carrying of a heavy burden and has inspired movies, songs, and stories since Coleridge’s time. Chelsea Kimberling and Rainer F. Buschmann

The Romantic vision of the sea popular in the nineteenth century flowed from the confluence of a unique set of historical and cultural circumstances. But, the same trends affected how people on the receiving end of European expansion viewed the sea, especially in Japan. The Japanese have always seen their island nation as a place apart and protected by the sea, particularly during more than two centuries of self-imposed isolationism. As foreigners began to test their resolve, artists responded with visions of the sea that reflected a collective anxiety about geopolitical change, notably in Katsushika Hokusai’s “Under the Wave off Kanagawa” (1830-33), which suggests both Japan’s vulnerability and its potential for overseas expansion.

The Romantic movement had a defining impact on the way people view the oceans of the world and see themselves in relation to the maritime environment, yet it has simultaneously distorted popular interpretations of the seas’ influence on culture. Written, visual, and performance art of all genres have always helped people mediate the human experience of the maritime world. It is certainly possible to detect elements of Romanticism in the quest narrative that forms the basis of sea narratives starting with Gilgamesh or Odysseus, but those heroes are deeply engaged with the world as it is and do not stand aloof from it. Moreover, the natural world through which they move does not represent freedom from an ordered, mechanistic society and a personal challenge that will lead to the Romantic’s “temptation, fall, and redemption.” Rather than being a threat to or opportunity for personal fulfillment, the sea is a perennial danger to communal well-being, something to be overcome by a combination of wit and divine intervention.

Economic and technological changes over the past century and a half have made the sea—both on the surface and below it—accessible in ways that it never was before. This has had an enormous impact on people’s collective attitudes toward the natural environment and given us a new, more immediate appreciation of the world’s oceans. It has also forced us to reevaluate our relationship with the sea and to acknowledge both our debt and our obligation to this great reservoir of our cultural life. Lincoln Paine

FURTHER READING: Alexander, Caroline. 2003. The Bounty: The True Story of the Munity on the Bounty. New York: Penguin.

Auden, W H. 1951. The Enchafed Flood, or the Romantic Iconography of the Sea. London: Faber & Faber.

Barczewski, Stephanie L. 2004. Titanic: A Night Remembered. London: Hambledon.

Biel, Steven. 1996. Down with the Old Canoe: A Cultural History of the Titanic Disaster. New York: Norton.

Brinnin, John Malcolm. 2000. The Sway of the Grand Saloon: A Social History of the North Atlantic. New York: Barnes & Noble.

Buzurg ibn Shahriyar of Ramhormuz. 1981. The Book of the Wonders of India: Mainland, Sea and Islands, Translated by G.S.P Freeman-Grenville. London: East-West.

Constable, Olivia Remie. 1994. Trade and Traders in Muslim Spain: The Commercial Realignment of the Iberian Peninsula, 900-1500. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Crosby, Alfred W 1973. The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492. Westport, CT: Greenwood.

Flecker, Michael. 2001. “A Ninth-Century ad Arab or Indian Shipwreck in Indonesia: First Evidence for Direct Trade with China.” World Archaeology 32: 335-54.

Date added: 2025-10-14; views: 204;