The Celtic Languages and Cultural Survival

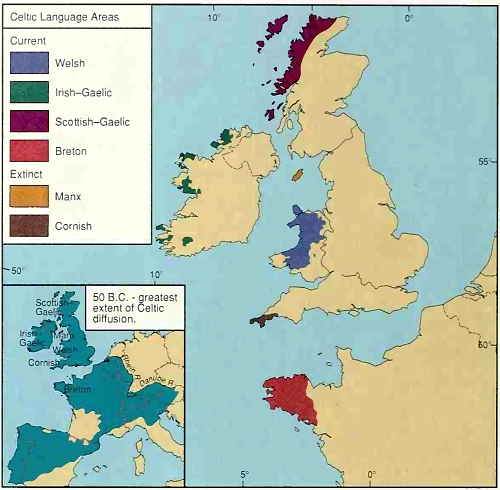

The changing distribution of the Celtic languages illustrates some of the dynamics of language change. Prior to the invasion of the British Isles by Germanic-speaking Angles, Saxons, and Jutes, Celtic languages were spoken throughout Britain, Ireland, and northwestern France. Six distinct Celtic languages—Scots Gaelic. Irish Gaelic, Welsh. Breton. Cornish, and Manx—were spoken (Figure 4-10). Over the course of several hundred years, however. Celtic-speaking peoples were incorporated into Britain and France, and mail) Celtic speakers were discouraged from using their ancestral languages.

Figure 4-10. The Celtic Languages. Six Celtic languages were spoken by the original inhabitants of the British Isles and the French peninsula of Brittany. As a result of the political and economic dominance of the British and French governments, the Germanic and Romance languages, English and French, have proliferated, and the number of people speaking Celtic languages has declined steadily over the past two centuries

As English and French speakers achieved political domination of Great Britain. Ireland, and Brittany, the prevalence of the Celtic languages declined. Today, Manx and Cornish are extinct, and the number of people speaking the remaining Celtic languages is much reduced. The four living Celtic languages remain prevalent only in relatively isolated, rural areas. Moreover, few people continue to speak Celtic languages exclusively. In Ireland, for example, only about fifty thousand people speak Irish Gaelic exclusively. Most Celtic speakers also speak English or French.

Of the four living Celtic languages, Irish Gaelic (commonly referred to as Irish) is most likely to survive because of vigorous efforts on the part of Ireland's government to promote its use. This support for Irish Gaelic is associated with Ireland's long history of opposition to British colonial rule. During the nineteenth century, Irish nationalists intent on securing political independence from the United Kingdom became active in organizations that promoted the use of Irish in addition to political freedom.

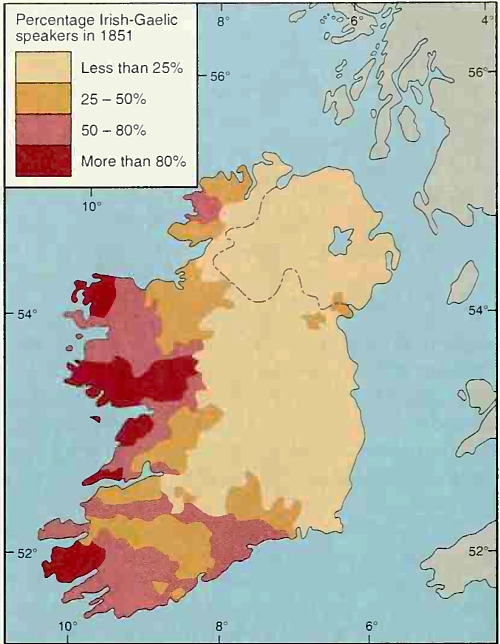

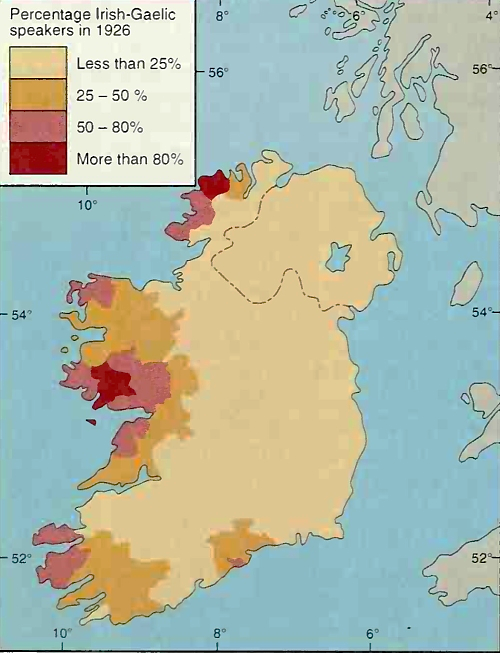

After Ireland was granted independence from Britain in 1921. the new Irish government was determined to promote the use of Irish as a means of encouraging Irish cultural awareness. Yet centuries of British domination had reduced the number of Irish speakers. A government-sponsored survey taken shortly after independence revealed that only 18 percent of the population could speak Irish, with most speakers concentrated in the rural western part of the island (Figure 4-11).

Figure 4-11. Irish Gaelic Speakers in Ireland. After several centuries of British rule, use of the Irish language retreated to the more rural and isolated part of the island

In the hope of preventing Irish Gaelic from dying out completely, the government enacted a law requiring that it be taught in Ireland's schools. It also required that signs be posted in Irish Gaelic, and it mandated that a minimum number of hours of radio and television programming be broadcast in that language. Slowly, the use of Irish Gaelic in Ireland began to increase. By the 1970s, over 28 percent of Ireland's inhabitants were conversant in Irish Gaelic and the percentage continues to increase.

The fate of Breton may be more problematic. Breton is spoken by under 20 percent of the 2.6 million people of Brittany, a region that was formally incorporated into France in 1532. France is a unitary state with a highly centralized government that in the twentieth century has actively discouraged the use of Breton. The increasing urbanization of Brittany's population also has contributed to the decline of Breton. By the late 1970s, only 8 percent of the young people in Brittany claimed to use Breton as frequently as French.

During the 1980s, political considerations encouraged the French government to reverse its traditional anti-Breton policies. Students were permitted to take Breton as a modern language, and two universities in Brittany were granted permission to grant degrees and teaching certificates in Breton. As a result, enrollments in Breton classes have been increasing. Nevertheless, some pro-Breton activists are concerned that future French governments might reverse this policy. Such a reversal might lead to the eventual extinction of Breton.

Date added: 2023-01-14; views: 662;