Human Phylogeny. Different Stages in the Early Embryonic Development of Vertebrates

Brief overview of human phylogenetic development. To better understand the evolution of the human body, it is helpful to trace its phylogenetic development. Humans and their closest relatives belong to the phylum Chordata, which includes approximately 50,000 species.

It consists of two subphyla:

- Invertebrata: the tunicates (Tunicata) and chordates without a true skull (Acraniata or Cephalochordata)

- Vertebrata: the vertebrates (animals that have a vertebral column)

Although some members of the chordate phylum differ markedly from one another in appearance, they are distinguished from all other animals by characteristic morphological structures that are present at some time during the life of the animal, if only during embryonic development (see G). Invertebrate chordates, such as the cephalochordates and their best-known species, the lancelet (Ranchiostoma lanceolatum) are considered the model of a primitive vertebrate by virtue of their organization. They provide clues to the basic structure of the vertebrate body and thus are important in understanding the general organization of vertebrate organisms (see D).

All the members of present-day vertebrate classes (jawless fish, cartilaginous fish, bony fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals) have a number of characteristic features in common (see H), including a row of vertebrae arranged in a vertebral column (columna vertebralis), which gives the subphylum its name (Vertebrata). The evolution of an amniotic egg, i. e., the development of the embryo within a fixed shell inside a fluid-filled amniotic cavity, was a critical evolutionary breakthrough that helped the vertebrates to survive on land.

This reproductive adaptation enabled the terrestrial vertebrates (reptiles, birds, and mammals) to live out their life cycles entirely on land and sever the final ties with their marine origin. When we compare the embryos of different vertebrate classes, we observe a number of morphological and functional similarities, including the formation of branchial arches (see B).

Mammals comprise three major groups: Monotremata (egg-laying mammals), Marsupialia (mammals with pouches), and Placentalia (mammals with a placenta). The placental mammals, which include humans, have a number of characteristic features (see I), including a tendency to invest much greater energy in the care and rearing of their young. Placental mammals complete their embryonic development inside the uterus and are connected to the mother by a placenta.

Humans belong to the mammalian order of primates, whose earliest members were presumably small tree-dwelling mammals. Together with lemurs, monkeys, and the higher apes, human beings have features that originate from the early adaptation to an arboreal way of life. For example, primates have movable shoulder joints that enable them to climb in a hanging position while swinging from branch to branch.

They have dexterous hands for grasping branches and manipulating food, and they have binocular, broadly overlapping visual fields for excellent depth perception.

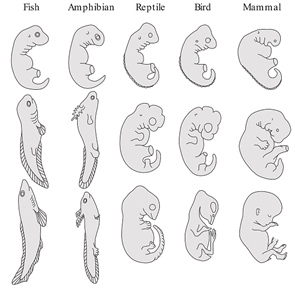

Different stages in the early embryonic development of vertebrates. The early developmental stages (top row) of fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals (as represented by humans) present a series of striking similarities that suggest a common evolutionary origin. One particularly noteworthy common feature is the set of branchial or pharyngeal arches in the embryonic regions that will develop into the head and neck.

Although it was once thought that the developing embryo of a specific vertebrate would sequentially display features from organisms representing every previous step in its evolution (“Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny,” the “biogenetic law” of Ernst Haeckel [1834-1919]), subsequent work has shown that the vertebrates share common embryonic components that have been adapted to produce sometimes similar (fins and limbs) and sometimes radically different (gills vs. neck cartilages) adult structures.

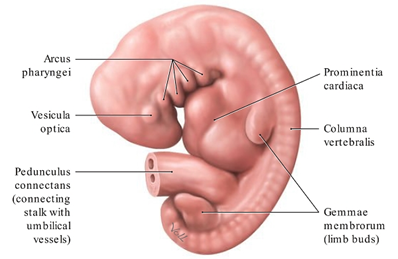

Formation of the branchial or pharyngeal arches in a 5-week- old human embryo. Left lateral view. The branchial or pharyngeal arches (arcus pharyngei) of the vertebrate embryo have a metameric arrangement (similar to the somites, the primitive segments of the embryonic mesoderm); this means that they are organized into a series of segments that have the same basic structure.

Among their other functions, they provide the raw material for the species-specific development of the visceral skeleton (maxilla, mandibula, auris media (middle ear ), os hyoideum, and larynx), the associated facial muscles, and the pharyngeal gut.

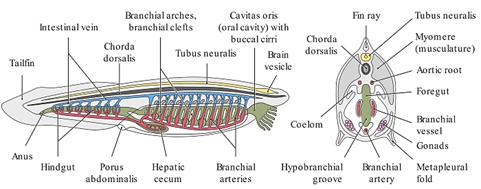

Basic chordate anatomy, illustrated by the lancelet (Branchiostoma lanceolatum). The vertebrates (including humans) are a subphylum of the chordates (Chordata), of which the lancelet is a typical representative. Its anatomy displays relatively simple terms of structures common to all vertebrates. The characteristic features of chordates include the development of an axial skeleton called the chorda dorsalis. The human body still has remnants of the chorda dorsalis, such as the nucleus pulposus of the intervertebral disks.

The chorda dorsalis is present in humans only during embryonic life, however, and is not a fully developed structure. Its remnants may give rise to developmental tumors called chordomas. Chordates have a tubular nervous system lying dorsal to the chorda dorsalis. The body, particularly the muscles, is composed of multiple segments called myomeres. In humans, this myomeric pattern of organization is most clearly apparent in the trunk. Another distinguishing feature of chordates is the presence of a closed circulatory system.

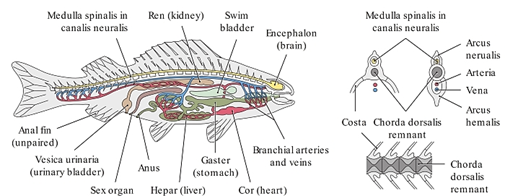

Basic vertebrate anatomy, illustrated by the bony fish. The vertebrates are the subphylum of chordates from which humans evolved. With the evolution of fish, the chorda dorsalis was transformed into a vertebral column (spinal column). The segmentally arranged bony vertebrae of the spinal column encircle remnants of the chorda dorsalis and have largely taken its place.

Dorsal and ventral arches arise from the vertebral bodies. The dorsal arches (vertebral or neural arches) in their entirety make up the canalis neuralis, while the ventral arches (hemal arches, arcus hemalis) form a caudal “hemal canal” that transmits the major blood vessels. The ventral arches in the trunk region are the origins of the ribs.

Date added: 2023-08-28; views: 879;