Africa, Central. Foragers, Farmers, and Metallurgists

Archaeologists know less about the prehistory of Central Africa through the last 10 000 years than about any other part of the continent. This is only in part because of the difficulties of working in tropical forest: indeed, some of the least-known areas are in the woodlands along the northeastern fringes of the Congo Basin.

More important have been the effects of decades of political instability and an underdeveloped infrastructure that goes back to the colonial period. Over the last decade, however, some parts of Central Africa - especially in the northwest - have yielded a great deal of information on ancient occupations in this period.

Moisture levels in Central Africa increased dramatically from the terminal Pleistocene, much drier than the present, to the early Holocene, which would have been generally wetter than today. This corresponded to a great increase in forests over the same period. However, models of a uniform expansion of tropical forest out of Late Pleistocene refugia are oversimplified.

There seems to have been a great deal of local diversity in plant associations, as well as significant regional variations in rainfall, temperatures, and seasonality, through this period. Instead of thinking about environmentally determined depopulations and repopulations over Central Africa as a whole, we must imagine human communities adapting to a wide variety of circumstances and resources in different areas and at different times.

The beginning of the Holocene saw all of Central Africa occupied by foraging communities. Little evidence of these populations is left, aside from their stone tool industries, which show a good deal of continuity from the Late Pleistocene. Not surprisingly, in the center of the continent, these industries are diverse, with stone tool-kits in the northwestern part of Central Africa showing some similarities with adjacent areas of West Africa, eastern industries exhibiting some resemblances to East Africa, and so on.

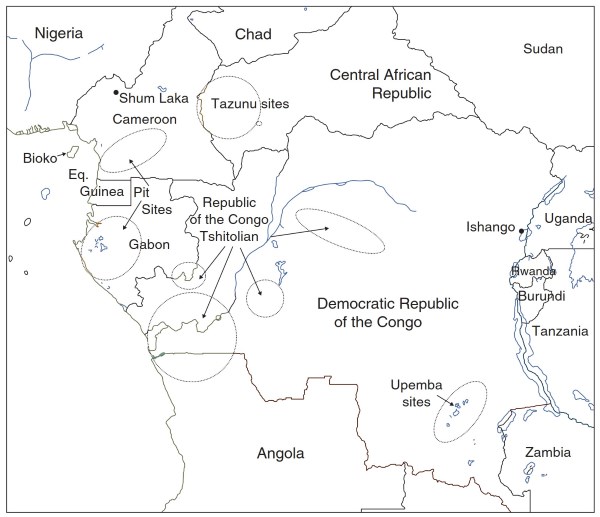

Perhaps most uniquely Central African is the Tshitolian industry, found primarily in the west, in Republic of the Congo and Democratic Republic of the Congo, northwestern Angola, and parts of Gabon. The Tshitolian seems to be derived from the Late Pleistocene Lupemban industry, and shares with the Lupemban an important component of heavy-duty bifacial tools, as well as arrowheads and microlithic tools. In other parts of Central Africa, microlithic industries predominate and the bifacial tools are rare or absent. We know little about the lifeways of these populations, but the available evidence indicates that for the most part they were broad-spectrum, mobile hunter-gatherers.

Late Pleistocene lakeshore sites like Ishango in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, with their extraordinary bone harpoon points and evidence for fishing and hunting, exhibit striking similarities to Holocene sites in similar environments in East Africa, but there is no firm evidence for the persistence of this lacustrine adaptation in Holocene Central Africa (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Some of the sites and traditions mentioned in the text. The extent of archaeological traditions is approximate

Just after 7000 years ago, significant innovations appeared in the economic and technical adaptations of communities in the northwestern part of the region. On what is now the frontier between southeastern Nigeria and Cameroon, archaeologists working at sites like Shum Laka have found evidence for consumption of nuts from the incense tree (Canarium schweinfurthii), a wild species that would be increasingly exploited by humans over the succeeding millennia, as well as the first evidence for pottery in the region.

At the same time, larger bifacial (but not Tshitolian) tools appear among the microlithic stone tools that earlier dominated in this area, as does the first evidence for ground/polished stone tools. In later periods, such tools would be used in horticulture and forest clearance.

The Early-/Mid-Holocene appearance of these new cultural elements signals the origins of a very different adaptation to life in Central Africa, one eventually involving increased sedentism, a concentration on particular wild plant foods and increased levels of environmental manipulation. Over the next four millennia, these elements would come to dominate archaeological assemblages in this part of the region, as important ‘semi-domesticates’ such as oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) were added to local economies. This adaptation would culminate in the farming villages of southern Cameroon and Gabon, during the first millennium BC.

These sites are characterized by the occurrence of large numbers of deep pits, probably used for storage and garbage disposal; these pits frequently contain pottery, Canarium, and oil palm remains, and also in some cases the remains of domesticated plants and animals, including millet, banana (originally a Southeast Asian domesticate), and sheep/ goats. These pit sites are probably related to sites of a similar period in western Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The spread of these communities into Central Africa from the northwestern part of the region is likely associated with the spread of Bantu languages, since the origins of those languages are in the Grassfields region around Shum Laka and the archaeological evidence agrees in general with linguistic evidence for the early expansion of Bantu languages. After the middle of the first millennium AD, few pits are found in sites in this area: the reason for this is unknown, but probably involves changes in settlement patterning during this period.

The prehistory of other regions is not as well, known through the mid-Holocene, but ground and polished stone axes similar to those found around Shum Laka occur in different parts of Central Africa. In some cases, for example, at Tchissanga and related sites on the coast of Republic of the Congo and in the Central African Republic (CAR), these are found with different kinds of pottery; in other cases, as on the Uelian sites of northern Democratic Republic of the Congo, in Angola and elsewhere, they exist as isolated discoveries, without significant cultural context.

In very few cases have these occurrences been dated, but those dates that do exist indicate a Mid-/Late- Holocene time period, and these sites are probably evidence of processes of economic intensification similar to those in the northwest - which, indeed, may be their ultimate origin. On the island of Bioko, now part of Equatorial Guinea, the use of stone tools, especially axes, would persist until the nineteenth century.

In western CAR, these developments are, by the early first millennium BC, associated with the appearance of the tazunu sites, megalithic sites in which upright standing stones are usually set in low artificial mounds. These are likely to have been funerary monuments, although not all excavated examples contain inhumations, and a tradition of tazunu construction may have continued in the area until a few centuries ago. The construction of these impressive monuments, and their association with single burials (where any are found), would seem to imply the existence of some degree of social ranking in western Central African Republic through this period (see Africa, Central: Great Lakes Area).

The appearance of iron artifacts would eventually transform the economies and even the ideologies of Central African societies, but this did not happen immediately. Indeed, the available archaeological evidence indicates that early iron technologies were incorporated into the already-existing cultural systems discussed above, and that traditional assumptions of an Iron Age, a sudden break with earlier practices, seem to be particularly misleading in this case.

The first evidence of iron production (in fact, very frequently the slag by-products of iron smelting and forging) appears on sites in northwestern Central Africa during the first millennium BC. Establishing the precise timing of that appearance is difficult, in part because of difficulties with radiocarbon calibration during the middle of that millennium.

However, both a habitation site associated with the tazunu of the CAR and one of the pit sites in southern Cameroon have yielded dates for iron working of about 2600 years ago, and so between the ninth and the sixth centuries BC. This generally agrees with dates on some West African iron-working sites as well, but more work remains to be done on the origins of this technology in subSaharan Africa.

Sites with iron from this area, in Gabon and in Republic of the Congo, became more common by the late first millennium BC, and through the ensuing centuries in other areas of Central Africa, until by perhaps AD 800 iron was being used throughout Central Africa (except on Bioko, as noted above, and perhaps by isolated foraging groups elsewhere). Over this same period, the use of stone tools for the most part ceased, presumably replaced by iron. In general, this parallels the introduction of iron into East Africa, although the exact routes by which that introduction took place are unknown.

Over the ensuing centuries, as iron technologies became established through the region, we see the development of larger-scale societies, the extension of trade networks and evidence for increasing social complexity in some parts of Central Africa. This is most strikingly demonstrated in the Upemba Depression of southeastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, where a remarkable series of high-status grave sites, dating to between the eighth and eighteenth centuries AD, indicate the processes of social differentiation and ideological development that culminated in the historically known Luba state.

There is scattered archaeological evidence for significant trading networks and iron and copper production in western Democratic Republic of the Congo at the same time period, as well. In other areas - the Central African Republic and northwestern Democratic Republic of the Congo, for example - the village-level societies that developed in the first millennium BC and early first millennium AD remained the dominant economic and political units into the colonial period. As in much of the rest of Africa, there has been little archaeological investigation of recent centuries, and still less of the period of European contact.

Over the last two millennia, archaeological data are increasingly supplemented by data from linguistic and historical research. These sources provide information on social and cultural processes that are not easily approached archaeologically - the details of the expansion of Bantu languages, the developing relations between farmers and foragers (Pygmy/BaTwa) in Central Africa and the interplay between ideology and sociopolitical relations across the region as a whole, for example. Only through such integrated approaches will researchers be able to approach a more complete picture of the Central African past.

Date added: 2023-11-08; views: 623;