The Hydrologic Cycle. Reservoirs and Residence Time

The Earth’s water occurs as a liquid in the oceans, rivers, lakes, and below the ground surface; it occurs as a solid in glaciers, snow packs, and sea ice; it takes the form of water droplets and gaseous water vapor in the atmosphere. The places in which water resides are called reservoirs, and each type of reservoir, when averaged over the entire Earth, contains a fixed amount of water at any one instant.

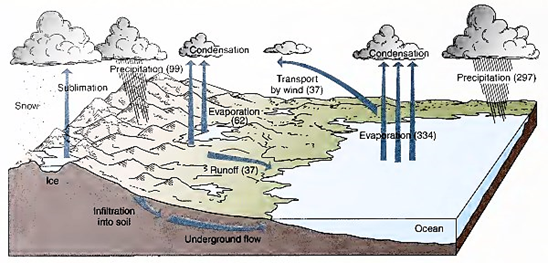

But water is constantly moving from one reservoir to another, as liquid water evaporates from the oceans into the air, icebergs melt in the oceans, rains fall on the land, and rivers flow back to the sea. This movement of water through the reservoirs is called the hydrologic cycle (fig. 1.17).

Figure 1.17. The hydrologic cycle and annual transfer rates (thousands of cubic kilometers per year). Snow and rain together equal precipitation. Sublimation, the direct transfer of ice to water vapor, is included under evaporation. Surface flow and underground flow are considered as land runoff

Evaporation takes water from the surface of the ocean into the atmosphere; most of this water returns directly to the sea, but air currents carry some water vapor over the land. Precipitation transfers this water to the land’s surface, where it percolates into the soil; fills rivers, streams, and lakes; or remains for longer periods as snow and ice in some areas. Melting snow and ice, rivers, groundwater, and land runoff move the water back to the oceans to complete the cycle and maintain the oceans’ volume. For a comparison of the water stored in the Earth’s reservoirs, see table 1.3.

In local areas, excess water may evaporate from the land and excess precipitation may occur over the sea, but on a worldwide average, the cycle operates with a net removal of ocean water by evaporation, a net gain of water on land as a result of precipitation, and a return of the excess water on land to the sea by rivers and land drainage.

The properties of climate zones are principally determined by their surface temperatures and their evaporation-precipitation patterns; the moist, hot equatorial regions; the dry, hot subtropical deserts; the cool, moist temperate areas; and the cold, dry polar zones.

Differences in these properties, coupled with the movement of air between the climate zones, moves water through the hydrologic cycle from one reservoir to another at different rates. The transfer of water between the atmosphere and the oceans alters the salt content of the oceans’ surface water, and, with the seasonal and latitudinal changes in surface temperature, determines many of the characteristics of the world’s oceans.

Reservoirs and Residence Time. Because the total amount of water on Earth is nearly constant, the hydrologic cycle must maintain a balance between the addition and removal of water from the Earth’s water reservoirs. The rate of removal of water from a reservoir must equal the rate of addition to it, for if the balance is disturbed one reservoir will gain at the expense of another.

The time that the water spends in any one reservoir is called its residence time. A large reservoir has a long residence time because it takes a long time to move all the water in that reservoir through the hydrologic cycle; small reservoirs have short residence times, and their water can be replaced comparatively quickly. The size of the reservoir also determines how it reacts to changes in the rate at which the water is gained or lost.

Large reservoirs show little effect from small rate changes, whereas small reservoirs may alter substantially when exposed to the same variation in rates of gain or loss. For example, if the ocean volume decreased by 6 ½ % and that volume of water were added to the land ice, the result would be a 400% increase in the present volume of land ice but only a 250-m (820-ft) drop in sea level. This example reflects the changes that have occurred on Earth during the major ice ages.

About 396,000 km3 (94,644 mi3) of water move through the atmosphere each year. Because the atmosphere holds the equivalent of 15,300 km3 (3,580 mi3) of liquid water at any one time, a little arithmetic shows that the water in the atmosphere can be replaced twenty-six times each year. Atmospheric water has a very short residence time. The residence time for water in the other, larger reservoirs is much longer.

For example, it would take 37,027 years to evaporate and pass the water from all of the oceans through the atmosphere, to the land as precipitation, and back to the oceans via rivers. Further study of water’s movement shows us that annually 334,000 km3 (79,826 mi3) is evaporated from the oceans, and 62,000 km3 (14,818 mi3) is evaporated from land. When the water returns as precipitation, 297,000 km3 (70,983 mi3) is returned directly to the sea surface, and 99,000 km3 (23,660 mi3) returns to the land. However, the excess gained by the land (37,000 km3, or 8,843 mi3) flows back to the oceans in rivers, streams, and groundwater (see fig. 1.17).

Date added: 2023-11-08; views: 915;