Actors in and Models of Public Policy Agenda Setting

Actors in Agenda Setting. Many individuals and institutions are involved in shaping health policy agendas, including political officials, civil society organizations, United Nations agencies, and philanthropic foundations (Table 1).

Table 1. Actors in public health policy agenda setting

Kingdon (1984) distinguishes between visible and hidden participants. Senior political and administrative officials including prime ministers, legislators, ministers of finance, and leaders of international donor agencies are likely to be more visible, moving large problems and issues on to the agenda, such as lack ofhealth-care access for the poor and the reform of national health sectors.

Specialists including scientists, doctors, academics, and career civil servants may play less visible but nevertheless crucial roles, proposing policy alternatives that can address these problems, hoping to convince political leaders to take the issue seriously. However, this distinction is not clear-cut, and there are many instances where specialists - often as part of large policy networks - take on visible roles, contributing to the emergence of broad issues on to national and international health agendas.

Walt (2001) notes a transformation in the relationships among international actors involved in health that has influenced agenda-setting processes. After World War II, a system of vertical representation emerged globally, as states cooperated in international health through the United Nations system and particularly the World Health Organization.

Over time a complex array of actors became involved in health, and the role of the UN system diminished. She argues that the global health system is now best characterized as one of horizontal participation, with partnerships (and conflicts) among a broad array of actors. A particularly notable development since the 1980s is the growing role of the World Bank in global health, and the tensions this emergence has caused between this institution and the World Health Organization, which originally had the mandate for global health coordination (Buse and Gwin, 1998).

Another prominent development is the increasing role of private actors in global health, including philanthropic foundations (particularly the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation) and a proliferation of public-private partnerships that link pharmaceutical companies, foundations, international agencies, nongovernmental organizations, and donor governments in cause-specific initiatives, such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GFATM), and the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations (GAVI).

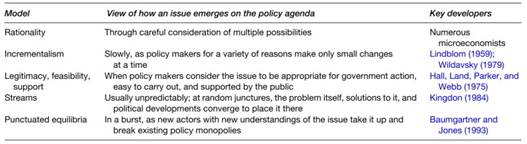

Early Models of Agenda Setting. Researchers have developed a number of public policy agenda-setting models that consider actors, processes, and contexts (Table 2). Early frameworks include the rationality and incrementalist models, and a model invoking the concepts of legitimacy, feasibility, and support. Newer frameworks include the streams and punctuated equilibria models. Public health policy researchers have employed these in order to investigate health policy agenda-setting processes. In recent years a body of work on international relations has come to influence thinking on health policy agenda setting, and it is worth considering ideas from this field as well.

Table 2. Models of public policy agenda setting

The rationality model was founded on a presumption that policy makers define carefully the nature of the problems they face, propose alternative solutions, evaluate these solutions on the basis of a set of uniform and objective criteria, and select and implement the best solutions. It continues to be employed by many economics- oriented policy analyses that use cost-benefit calculations to select among competing alternatives. As noted above, in health policy the desire to inject rationality into resource allocation decisions is the impetus behind the development of the disability-adjusted life year and underpins much analysis in the cost-effectiveness tradition.

Many scholars who have studied the political dynamics of policy making believe that the rationality model does not capture how agendas are formed in practice, questioning the presumption that actors deliberate in a logical, linear fashion (Lindblom, 1959; Buse et al., 2005).

Among the points they raise are that actors have limited information, are not able to imagine all the alternatives, even if cognizant of multiple alternatives are not likely to consider each systematically, hold ambiguous goals, and change these goals as they act. An alternative understanding of the agenda-setting process, termed incrementalism, emerged that takes into account a number of these critiques (Kingdon, 1984).

Drawing in part from research on public budgetary processes, scholars have postulated that policy makers are inclined to take the status quo as given and carry out only small changes at a time, making the policy-making process less complex, more manageable, and more politically feasible than a comprehensive rational deliberative process would entail (Lindblom, 1959; Wildavsky, 1979).

Applying this idea to health, we observe that one of the most reliable predictors of the size of a national health budget, as well as its subcomponents such as hospital construction and maternal and child health, is the previous year’s budget, evidence that policy makers alter their priorities slowly.

Hall and colleagues produced one of the earliest works that considers the role of power in public policy agenda setting (1975). They argue that an issue is more likely to reach the policy agenda if it is strong on three dimensions: legitimacy, feasibility, and support. Legitimacy refers to the extent to which the issue is perceived to justify government action.

For instance, the control of tobacco use in the United States formerly had little legitimacy, defined in these terms, but this situation has changed. Feasibility refers to the ease with which the problem can be addressed, and is shaped by factors such as the availability of a technical solution and the strength of the health system that must carry out the policy. For instance, the development of a vaccine for polio made control of this disease much more feasible. Support refers to the degree to which interest groups embrace the issue and the public backs the government that is to address it.

Health-care reform in the United States failed under the Clinton administration in part because organized medical interests mobilized to oppose its enactment.Newer Models of Agenda Setting. In the most influential model of the public policy agendasetting process, Kingdon (1984) challenges traditional models of agenda setting that conceptualize it as a predictable, linear process. He argues that agenda setting has a random character in which problems, policies, and politics flow along in independent streams.

The problems stream is the flow of broad conditions facing societies, some of which become identified as issues that require public attention. The policy stream refers to the set of alternatives that researchers and others propose to address national problems. This stream contains ideas and technical proposals on how problems may be solved. Finally, there is a politics stream.

Political transitions, global political events, national mood, and social pressure are among the constituent elements of the politics stream. At particular junctures in history the streams combine, and in their confluence windows of opportunity emerge and governments decide to act. The opening of these windows usually cannot be anticipated. Prior to the combining there may be considerable activity in any given stream, but it is not until all three streams flow together that an issue emerges on the policy agenda.

Several scholars have adapted ideas from Kingdon’s model to explain how particular health issues have emerged on policy agendas. Reich argues that five political streams - organizational, symbolic, economic, scientific, and politician politics - all favored child over adult health through the 1990s, explaining the higher position of the former on the international health agenda (Reich, 1995). By organizational politics he means efforts by organizations such as the WHO and World Bank to use their resources to enhance their authority.

Symbolic politics concerns how actors use imagery to advance their positions - for instance UNICEF’s effective use of the tragedy of child ill health to mobilize social institutions and raise funds. Economic politics concerns the ability of for-profit organizations to advance their interests, such as the power that the tobacco industry has wielded to block efforts to control this substance. Scientific politics concerns the influence of financial support and other political factors on public health research agendas.

These four streams shape the cost-benefit calculations of national politicians - the politicians’ stream - concerning which problems to place on national policy agendas. Ogden et al. have also drawn on Kingdon’s ideas in their research on tuberculosis (Ogden etal., 2003). They demonstrate that the emergence of the HIV/AIDS epidemic contributed to the opening of global policy windows, facilitating advocacy networks to promote directly observed treatment, short- course (DOTS) as a treatment of choice for tuberculosis.

Baumgartner and Jones (1993) have developed another model that challenges the rationality and incrementalist frameworks. Their punctuated equilibria model postulates periods of stability with minimal or incremental change, disrupted by bursts of rapid transformation. Central to their model are the concepts of the policy image and the policy venue. The policy image is the way in which a given problem and set of solutions are conceptualized.

One image may predominate over a long period of time, but may be challenged at particular moments as new understandings of the problem and alternatives come to the fore. The policy venue is the set of actors or institutions that make decisions concerning a particular set of issues. These actors may hold monopoly power but will eventually face competition as new actors with alternative policy images gain prominence.

When a particular policy venue and image hold sway over an extended period of time, the policy process will be stable and incremental. When new actors and images emerge, rapid bursts of change are possible. Thus, the policy process is constituted both by stability and change, rather than one or the other alone, and cannot be characterized exclusively in terms of incrementalism or rationality.

For instance, Baumgartner and Jones show that little changed in U.S. tobacco policy in the first half of the twentieth century as the subject generated little coverage in the U.S. media, government supported the industry through agricultural subsidies, and the product was seen positively as an important engine for economic growth. Beginning in the 1960s, however, health officials mobilized, health warnings came to dominate media coverage, and the industry was unable to counter a rapid shift in the policy image that focused on the adverse effects of tobacco on health.

Shiffman et al. (2002) have used the punctuated equilibria model to examine the ebbs and flows in global attention for polio, tuberculosis, and malaria control. They argue that priority for each of these three diseases rose surprisingly and rapidly at different historical junctures, in ways not explainable by the rationality and incrementalist models of the agendasetting process. In each case the rise of attention conformed to a punctuated equilibria dynamic, in which new actors became involved with the issue, creating new images of the nature of the problem and of its solutions.

Date added: 2024-02-18; views: 915;