Environmental Factors. Access to Health Care

A sense of connectedness with one’s family has been associated with a multitude of positive health outcomes in adolescence. Teenagers who feel their parents love and support them are more likely to attend school and less likely to abuse substances, become sexually active, and have mental health problems. Connected families act as role models, offer adolescents loving support to make good decisions, and set boundaries for misbehavior.

In the past, extended families were more likely to live communally and thus were better able to influence adolescent behavior; presently, the smaller nuclear family is increasingly common, and families tend to exert less power. Many adolescents live in single-parent households or may lack supervision when their parents work.

Hundreds of thousands of teenagers are orphans due to diseases such as HIV and are obliged to become heads of households to care for their younger siblings, often leaving school to do so. Other orphaned adolescents are sent to other households to be fostered, or become homeless.

Education is also a critical factor in an adolescent’s well-being. School not only provides the career training necessary for adolescents to become self-sufficient but also teaches them how to socially interact. More schooling has been associated with many positive outcomes, especially in females, including later ages of marriage, lower lifetime fertility rates, improved infant survival, and higher earning power.

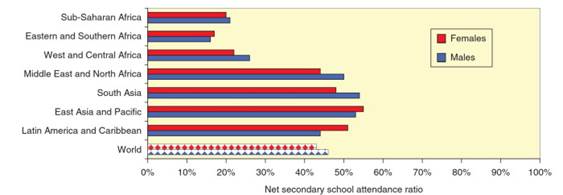

Fortunately, adolescents are more likely to complete their secondary education now than ever before, although a gap still exists between industrialized and developing countries (Figure 3). Girls are less likely than boys to continue schooling, especially during middle to late adolescence.

Figure 3. Net secondary school attendance ratio (1996-2005), selected regions. Net secondary school attendance ratio is the number of secondary school-aged children attending secondary school as a ratio of the total number of secondary school-aged children. Data exclude China. Data from most recent time available within time period. Adapted with permission from UNESCO Institute for Statistics, http://www.uis.unesco.org

The gender gap is most pronounced in Africa and West Asia, but there have been significant improvements in the gender gap in northern Africa, and in South and East Asia. Many young girls leave school early due to early marriage or pregnancy. Boys may not complete their schooling due to pressures to work to provide economic relief to their families, or to become soldiers.

The International Labour Organization states that the minimum age for full-time work should be at least 15 years, and should be after the completion of compulsory education. Despite this fact, many youth work at younger ages, often for low wages for unskilled work in poor conditions. In general, the proportion of young people in the workforce has fallen worldwide. Young people often migrate to urban areas in search of paying jobs as part of the worldwide trend toward urbanization. Such youth can distance themselves from their family’s influence and previously known social structure, placing them at risk for economic and other exploitation.

Some of these young people eventually sell sex for survival, as they lack training or skills to more fully participate in the workforce. Although adolescents today are less likely to live in poverty, those living in regions in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa are stressed by lack of access to food and other basic human needs.

Education systems need to adequately prepare students for their economic well-being by teaching them the skills they need in the modern global marketplace. Globalization has created new economic opportunities for many adolescents.

For others, market values cause financial stress and weakening of social networks. In many ways, adolescents are at the forefront ofglobalization, as they are interested in innovation and technology and thus are more likely to participate in international forms of media such as the Internet. Via the World Wide Web, they can experience, export, and import cultures from thousands of miles away, exchanging value systems and other lifestyle choices.

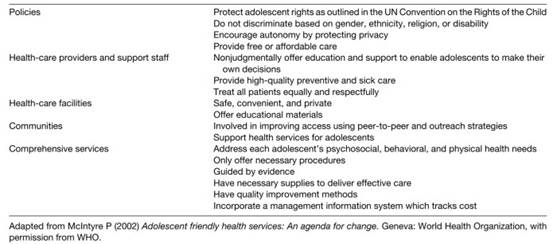

Access to Health Care.Many adolescents lack access to adequate health care. Programs that manage adolescent care by grouping them nondifferentially with children or adults do not effectively address the unique needs of this population. Providers may miss opportunities to educate and intervene early regarding adolescent behavior and lifestyles. Accordingly, WHO has detailed recommendations on the components of adolescent-friendly health services (Table 1).

Table 1. Selected characteristics of adolescent-friendly health care

Similar to adult services, health care for adolescents should be easily accessible and affordable, address common diseases, provide high-quality services, and offer continuity of care. Helping youth negotiate and learn to access the range of services in preestablished community networks is an important aspect of health education and future access to care. Because so many of their concerns are of a sensitive nature and may be culturally taboo, assurance of confidential services is vital for adolescent patients.

Teenagers who are not confident in their privacy are less likely to seek health care in the first place, and are less likely to receive certain medical services such as testing for sexually transmitted infections and early prenatal care. Judgmental and unsympathetic attitudes of health-care workers only serve to further marginalize this at-risk group.

Adolescents tend to delay seeking medical care until they are truly distressed for a number of reasons. They often lack the judgment to recognize symptoms, are in denial about their potential diagnosis, or wish to hide their problems from their family or peers. Barriers to care such as extended waiting times, lack of transportation, or long distances to services are particularly cumbersome for teenagers.

School-based services can eliminate some barriers by providing care on site to those in the educational system, but do not address groups at highest risk, including the homeless, sex workers, and those who have dropped out or have been expelled from school. Outreach services to these highly vulnerable populations can be highly effective, but are not universally available in many areas of highest need.

Adolescents who do not trust traditional health services may seek other sources of advice, such as peers or family members. These sources may not be reliable and can delay appropriate care, causing aggravation of the child’s condition.

Date added: 2024-02-03; views: 683;