Mother-to-Child Transmission

Vertical transmission rates in many developing countries remain as high as 10-20% even though the likelihood an HIV-1-infected mother will transmit HIV-1 to her infant has been reduced to less than 1% in the United States and Europe. As a result, more than 500 000 infant HIV infections occur each year in sub-Saharan Africa and other resource-limited settings (UNAIDS/WHO, 2006).

Differences in transmission rates may be attributed in part to poor access and uptake of HIV diagnostic testing and prevention interventions in those regions with the highest HIV prevalence among women of reproductive age. A number of other factors, including infant feeding practices, rates of coinfections, and breast pathology, also contribute.

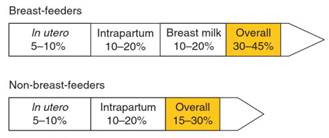

HIV may be transmitted from mother to infant during pregnancy (in utero), during delivery (intrapartum), or through breast-feeding. In the absence of antiretroviral therapy, the overall transmission rate among non-breast- feeders is approximately 15-30% (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Timing and absolute rates of vertical HIV-1 transmission

Among non-breast-feeding women, approximately two-thirds of mother-to-child HIV-1 transmission events occur during delivery when the baby passes through the birth canal and is exposed to infected maternal blood and genital secretions. The remaining infant infections are attributable to in utero transmission.

In resource-limited settings, the majority of HIV-1- infected women breast-feed their infants due to lack of clean water or safe alternatives to breast milk, or due to stigma associated with not breast-feeding in regions where breast-feeding is the norm.

Consequently, overall rates of transmission in the absence of antiretroviral prophylaxis increase to 30-45% (John and Kreiss, 1996) and several studies suggest that breast milk exposure accounts for one-third to one-half of these transmission events. Transmission during the in utero and intrapartum periods contributes the remainder of infections in proportions similar to those among non-breast-feeders (see Figure 6).

Valuable data on breast milk transmission rates were collected in a randomized clinical trial of breast-feeding versus formula feeding in Kenya where 16% of infants acquired HIV-1 via breast milk during the 2-year study period (Nduati et al., 2000). The proportion of transmission events attributable to breast-feeding was 44%. A subsequent meta-analysis of nine cohorts of HIV- 1-infected breast-feeding mothers found similar results, reporting that the proportion of infant infections attributable to breast-feeding after the first month postpartum was 24-42% (Coutsoudis et al., 2004).

Risk of breast milk transmission after the first month appears to remain relatively constant over time, with transmission events continuing to accumulate with longer duration of breast-feeding (Coutsoudis et al., 2004). During this period, the risk of infant HIV-1 acquisition per liter of breast milk ingested is similar to the risk of an unprotected sex act among heterosexual adults (Richardson et al., 2003).

High maternal plasma HIV-1 RNA load has been consistently associated with increased transmission and is considered the most important predictor of vertical transmission risk (Dickover et al., 1996). Several studies have demonstrated that reduction of HIV-1 viral load with antiretroviral drugs decreases overall rates of transmission, and this has become the mainstay of global prevention efforts.

HIV-1 viremia is highest in the setting of advanced disease and is usually associated with severe immunosuppression. High HIV-1 levels also occur during acute HIV infection, a time when a woman may not realize she is at risk for transmitting HIV-1 to her child. This has been examined in one study of women acquiring HIV-1 postpartum which found that there was a twofold increased risk of transmitting HIV-1 via breast milk during acute HIV (Dunn and Newell, 1992).

In addition to HIV-1 viral load, several biological and behavioral factors contribute to increased transmission risk. Ascending bacterial infections that cause inflammation of the placenta, chorion, and amnion have been associated with increased in utero transmission in several observational studies (Taha and Gray, 2000).

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), such as syphilis and gonorrhea, are considered to increase risk of transmission via this mechanism (Mwapasa et al., 2006), as well as chorio- amnionitis resulting from infection with local vaginal or enteric flora. However, the role of chorioamnionitis was not confirmed in a randomized clinical trial of more than 2000 women comparing antibiotic treatment of ascending infections to placebo which found no difference in transmission events between the two arms (Taha et al., 2006).

Other risk factors include infant gender and malarial infection of placental tissue, which has been inconsistently reported to increase mother-to-child HIV-1 transmission (Brentlinger et al., 2006). Strong associations have been found between infant gender and in utero transmission in several cohorts (Galli et al., 2005; Taha et al., 2005; Biggar et al., 2006). Female infants have a twofold increased risk of infection at birth when compared to male infants, perhaps because in utero mortality is higher for male HIV-1-infected infants than for females (Galli et al., 2005; Taha et al., 2005; Biggar et al., 2006).

Risk factors influencing the intrapartum period include genital tract HIV-1 levels, genital ulcer disease, delivery complications, and breaks in the placental barrier that may cause maternal-fetal microtransfusions. Genital ulcer disease has been shown to increase mother-to-child HIV-1 transmission at least twofold, both in the presence and absence of antiretrovirals (John etal., 2001; Chen etal., 2005; Drake et al., 2007).

The majority of genital ulcers are caused by HSV-2, and in regions with high HIV-1 sero- prevalence, HSV-2 seroprevalence is greater than 70% among women of reproductive age. Other risk factors for intrapartum transmission include prolonged duration of ruptured membranes and cervical or vaginal lacerations that occur during delivery. To restrict exposure to maternal HIV-1 in blood and mucosal secretions, cesarean section has been used effectively in many settings.

Two ofthe most important determinants ofbreast milk transmission risk are duration of breast-feeding and HIV-1 viral levels in breast milk. Introduction of food other than maternal milk may also exert an effect on HIV-1 transmission risk, potentially by compromising infant mucosal surfaces in the oropharynx and gut. Breast milk viral load increases with increased plasma viremia and also as a result of local factors.

These include breast inflammation resulting from mastitis, breast abscess, or other breast pathology, and inflammation within the breast milk compartment in the absence of clinical symptoms, which is known as subclincal mastitis (John et al., 2001). Rates of subclinical mastitis are reported to be as high as 30% among HIV-1-infected breast-feeding women, and several studies have found it to be associated with increased HIV-1 levels in breast milk, as well as greater risk of infant HIV-1 acquisition (Willumsen et al., 2003).

Transmission via Exposure to Blood Products. HIV transmission through blood transfusion and blood products has become rare after much progress in instituting careful screening and limiting the use of transfusions. Stringent screening of blood and blood products was a high priority at the start of the epidemic when it became known that transfusion with HIV-infected blood was an extremely efficient mode of transmission. In retrospective studies, approximately 90% of transfusion recipients were infected per single contaminated unit of blood (Donegan et al., 1990), and 75-90% of recipients of Factor VIII concentrate acquired HIV (Caussy and Goedert, 1990).

In developed countries, blood product screening for HIV includes serologic and nucleic acid donor testing. In Canada, the estimated risk ofHIV-infected donation being accepted was 1 per 7.8 million donations in the period from 2001 to 2005 (O’Brien etal., 2007), and in the United States, the estimated risk of an HIV-infected donation being accepted was 1 per approximately 2.1 million donations in 2001 (Dodd et al., 2002).

While great strides have been made to improve the safety of the blood supply in many countries, antibody screening of blood donors is not universally done in many developing countries due to the lack ofresources. In addition, some developing nations still rely on paid donors for their blood banks, and these paid donors have been shown to be at high risk for bloodborne infections (Volkow and Del Rio, 2005).

Occupational Exposure and HIV Transmission Risk. Health-care workers and laboratory personnel have a higher risk of HIV infection than individuals in other occupations. The average risk of HIV transmission is approximately 0.3% following percutaneous exposure to HIV-infected blood (see Figure 5) (Bell, 1997). Accidental percutaneous exposure carries the highest risk of subsequent infection and is the most important cause of occupational HIV transmission.

Needlesticks are the most common cause of a percutaneous accident, and factors that increase transmission from a needlestick accident include deep puncture with a large-bore needle, larger quantity of blood, and exposure to blood from an HIV- infected individual with a high HIV viral load (Cox and Hodgson, 1988). Contaminated surgical instruments have also been associated with percutaneous injuries.

Nonpenetrating accidents that involve intact skin are far less risky. Retrospective data suggest that immediate initiation of effective antiretroviral drugs can decrease risk of acquiring HIV after an occupational exposure (Cardo et al, 1997). Currently, recommended postexposure prophylaxis comprises a two- or three-drug antiretroviral regimen, depending on the nature and severity of the exposure (CDC, 2005).

Date added: 2024-02-18; views: 616;