The History of Greek Art

The history of Greek art can be conveniently divided into the general periods of Bronze, Dark, Geometric, Archaic, and Classical ages. These broad periods show distinct differences and changes that evolved over the course of centuries in Greece, the Aegean, Asia Minor, and southern Italy. The dates align themselves with historical and political events of the time and should be seen as general rather than specific. In addition, some of the trends continued from one era to another.

The Bronze Age is divided into the Cycladic, Minoan, and Mycenaean periods. The Cycladic and Early Bronze Age from 3000-2000 witnessed trade in obsidian and marble. The Cycladic region became known for its marble statues. Stone was shaped with chisels and then smoothed and polished with emery. The invention of the drill allowed the removal of material in the interior of a vase. The marble figurines were schematic though represented human forms. Most of them were standing, with long, oval, and backward-sloping heads. In pottery, there was the development of burnishing and incised patterns.

During the Middle Bronze Age, from 2000-1600, Crete became the center of Aegean culture. The rise of the Minoan palaces allowed the development of art. The remains of pottery show more complex and naturalistic motifs, which later became stylized. In Crete, a red-and-black effect was achieved through a new, special firing technique. During this period, there was a light-on-dark style featuring more complex patterns.

This developed into eggshell art decorations, the most sophisticated of which was the Kamares style, which showed polychrome on a black background and was named for the village of Kamares in Crete, where it was discovered. The mainland had a different style with the Gray Minyan ware, which was smooth and soapy to the touch and uniformly dark gray. In the Cyclades at this time, the type of pottery was matte-painted, with dark matte paint against a light background.

On Crete, frescoes in palaces became common. Since the palaces included large, open-walled spaces, frescoes allowed decorative motifs to be presented. The early period witnessed plain colors and linear patterns, while later frescoes had naturalistic and figured scenes. There were frescoes on the Cyclades, but none have been found on the mainland from this early period. This period also saw the rise of the potter’s wheel.

The Late Bronze Age I occurred on Crete and Mycenae from 1600-1450. The Cycladic period still had its own development of style and continued to be traded abroad. On the mainland at Mycenae, there was the grave circle, with its rich burials continuing into the Late Bronze Age II period (1450-1100). On the mainland, the rise of weaponry can be witnessed in the grave goods, representing the rise of a warrior caste. In pottery on Crete, there was a change to new shapes and the introduction of a different decorative technique.

There was now dark paint on a light background, as opposed to the earlier dark-on-light pattern. The Cyclades now copied the Minoan style. The Minoan styles first portrayed plants, flowers, and other floral designs, while the second period featured marine life such as octopuses and urchins. As time went on, the designs became more stylized. In the Late Bronze Age II, Mycenaean pottery became the norm. The forms were based on the earlier types, but now stylized. One of the most typical was the kylix, or stemmed goblet. Frescoes continued on Crete and the Cyclades, as well on the mainland at the Palace of Nestor at Pylos.

The end of the Bronze Age led to the decline of the Mycenaean period and the beginning of the Archaic Age. This period lasted from the twelfth century to 479, with the Persian Wars. The Dark Ages from 1200 to 1050 produced the SubMycenaean and Protogeometric styles. With the destruction of the Mycenaean and Minoan palaces, no great cities existed, but the previous styles continued. The forms, however, became more slack and ill organized. After this period, the previous shapes and forms continued, but they were now developed in a new way with increased technical improvements using a fast potter wheel.

The shapes and decorations became more exact and precise. The designs, lines and circles, were placed and incised on the vases while on the potter’s wheel before being fired. These in turn would lead to the Geometric period, which began around 900 and included continuing motifs such as zigzags and triangles, as well as new elements such as meanders and straight lines. This process then progressed to figures being introduced such as horses, lions, birds, and ultimately humans around 800. The figures were schematic and certain features became pronounced, such as broad chests and heads in profile.

The figures were abstract and portrayed stiffly, but by 700, they became more rounded and lifelike, showing individual movements. This is best seen in Attica, where Geometric consistency became clear. Around 750 in the potter’s region of Athens, various workshops begin to show individualistic designs and styles. Large amphorae (storage jars), kraters (mixing bowls), and cups became the most popular creations. This period also witnessed small terra-cotta and cast bronze figures. At the same time, foreign elements such as nonnative wildlife and abstract designs from Asia Minor and Egypt were introduced.

After this period, the Near-Eastern style from 725 to 590 made its appearance. This was evidenced by the importation of eastern and Egyptian influences on a more prominent scope. The Greek centaur was now joined by eastern monsters, Gorgons, griffins, chimeras, and harpies, which were now Hellenized. Two major trends developed, one in Corinth and the Peloponnese and the other in Athens and the Ionian cities of Asia Minor.

The Corinthian assimilation occurred during various periods, including the Early Protocorinthian (725-700), where alongside traditional geometric patterns new motifs such as animals, rosettes, and Near Eastern plants appeared. During the Middle Protocorinthian (700-650), the Corinthians adapted techniques from the east where incised details on the black-figure silhouette allowed the pale features to show through. In the Late Protocorinthian (650640) and Transitional/Ripe Corinthian (640-550) periods, the animals became larger and more crowded together. The process was slower than it had been in Athens with the Protoattic style (710-600).

The Early Protoattic (710-680) began with the Analatos Painter, who moved from the Late Geometric style from a silhouette to an outline style. In the next period, the Middle Protoattic (680-650), the Black and White style appeared. It was common to have motifs such as the Trojan War. The Late Protoattic (650-620) continued with consolidation until the Athenians adopted the Corinthian black- figure technique.

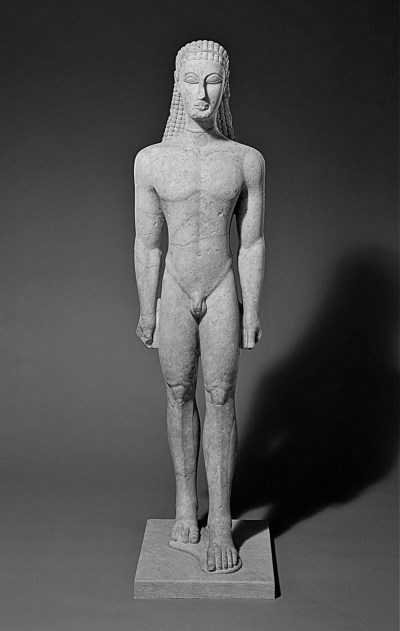

Also, from Egypt, came monumental statues that developed into the kouros (a standing nude young male figure that did not represent an individual person, but rather the idea of youth) beginning about 610. This style came from Egypt, with its two-millennium period of colossal figures. The Egyptians also influenced the Greeks in their monumental architecture with the peripteral temple of external rows of columns.

Marble statue of kouros. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Fletcher Fund, 1932)

Beginning about 590 to 530 was the High Archaic period, which corresponded to the age of tyrants. These individuals rose to power as champions of the poor and merchant middle class against the aristocracy (oligarchy), who were mainly landowners. These included figures such as Pisistratus of Athens, Polycrates of Samos, and Periander of Corinth, all of whom promoted the arts in their cities. During this period, myths became central in the arts and more natural.

The kouroi moved from the square type to a more natural pose. Male figures were portrayed nude, while women were clothed. Dedications to the gods took on more representations, as seen on temple pediments. It was also at this point that the two major orders, Doric and Ionic, became fully developed. In addition to sculptures on pediments, terra-cotta figures were used on buildings. This period also witnessed the further development of coins, which had begun earlier and now spread throughout the Aegean. Individual cities put their own mark on metal flans.

The Late Archaic Period from 530-480 witnessed the full development of the kouroi (male) and the complete domination of the Athenian market in pottery. The korai (female) developed into a graceful figure, usually enhanced by fashion, including wearing a cleaved tunic or dress, the chiton, which shows the influence from Ionia. The nude kouroi had a fully realistic anatomy in which the body’s movement could be seen in the twisting and shifting weight of the figure.

Pottery showed an evolution from the Archaic period into the Classical Age. The Archaic Age witnessed the development of the Black Style or Figure pottery, which was developed in the seventh century and continually used until the second century. The names of some of the artists of this time are well known from their signatures. The style first appeared in Corinth around 700. This earlier technique of the black figure now continued with a reverse technique in which the vase’s body was covered with a black glaze, while the decorated parts were left unworked in natural clay with the details shown with a painted relief line.

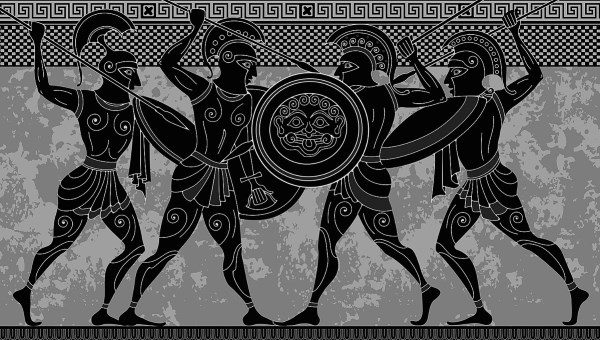

Black figure painting. (Tanya Borozenets/Dreamstime.com)

The painter or potter would paint the figure on the vase with a slurry or slip, which would turn black during the firing process. This involved a three-phase firing system. First, the vessel was fired in a kiln at a temperature about 800°C, which turned the vase reddish-orange. The second firing phase had the temperature raised to 950°C, with the vents closed to remove oxygen, which turned the vessel black. The final phase saw the vents reopened and the kiln cooled, which returned the vase to red while the painted figures from the second phase remained black.

The scenes were often from mythology, often featuring Heracles and the Trojan War. Interestingly, gods are not usually depicted, and Dionysus was never presented. Action scenes were very popular, with fights and hunts, while some examples presented passive banquet scenes. The figures of the early red-figure painters produced more realistic scenes. These changes now led to the Classical Age.

The Classical Age (480-450) is perhaps best evidenced in sculpture, where the full use of the realistic body first seen in the Archaic Age came to fruition. This evolution can be shown at the temple of Zeus at Olympia, where the fight among the Centaurs and Lapiths in their frenzied and savage fight occurred, but in specific groups. The opposite of this was the depiction of the chariot race of Pelops, which showed more emotion despite being static.

The depiction of events that show feeling and individuality became the hallmark of the Classical Age. Often the easygoing stance was on one leg, as opposed to the stiff forms of the kouroi. The twelve labors of Heracles are also displayed at Olympia in the metopes, showing confident and sensitive poses in great detail, even if they could not be seen from the ground. These types and styles were found throughout the Greek world, but not in such grandeur and detail.

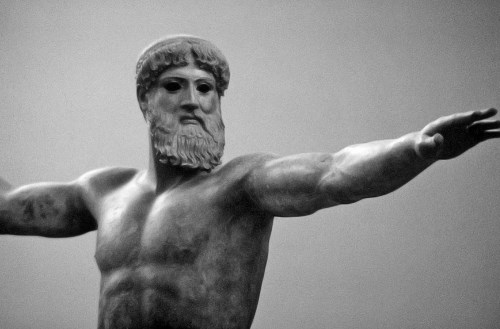

Several sculptors from this period are known, such as Nesiotes, Calamis, Pythagoras, Kritios, and Myron. These artists experimented with new styles. The bronze Zeus poised to throw his thunderbolt, an artwork discovered in the sea off Artemisium, showed a powerful musculature in a self-contained instance. These transitional pieces before 450 led to the great Classical artists, particularly Phidias, the best known. He developed a style seen in the Parthenon on the Acropolis, where he was the general contractor. Most of his other pieces are seen in later copies, but those on the Parthenon are his originals.

The style of Phidias is quiet and idealized, with self-contained and inwardlooking compositions. The Parthenon used many types of new styles and innovations. Typically, Doric temples did not have a frieze, but here, examples of Athena and other gods are on the pediments, frieze, and metopes. All the elements show a new confidence with proper perspectives.

The details are fine and exact, showing different styles. For example, two types of drapery exist—a plain contrast with heavy cloth barely showing a body, and an ornate one, with fine material and flesh showing through. This latter fine style became common in the late fifth century, showing the detail of clothing and flesh. During this same period, other buildings were constructed in Athens as part of the Periclean program, such as the Temple of Hephaestus.

With the increase in wealth in Athens, sculptured gravestones reappeared, meeting high artistic standards. During the period when Athens dominated the north using island carvers, Argos maintained its own program, with broader and heavier figures. Polycleitos, a contemporary of Phidias, was the best exponent. He aimed at full depth of body and naturalism to produce a harmonious design.

Classical statue of Poseidon. (Corel)

The first part of the fourth century witnessed another transitional period that led to the clear, relaxed figures, which were limper and more realistic or lifelike. In this period, the flesh and bones are best seen in the work of the sculptor Praxiteles. Work in terra-cotta, clay figures, continued but was not as pronounced. Further, creations in bronze continued with large works hollow-cast with glass eyes added. An example of the latter was the Delphi Charioteer. Common decorated bronze work was mirrors became more common. The older Archaic type, with elaborate and often complicated figures, was replaced with simple designs.

Vase painting did not suffer after the Persian Wars. The red- figure pottery or painting that developed around 530 during the time of Pisistratus in Athens continued, eventually replacing black-figure pottery as the predominant type. The figures were now created in the original red clay, allowing more detailed depictions since the lines could be drawn, rather than scraped out as previously done.

Red figure painting. (The Cleveland Museum of Art, Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund 1976.89)

In so doing, the depictions became sharper and clearer and had greater perspective. In addition, unlike black-figure pottery where the figures were shown in profile, red-figure paintings allowed the whole gamut of poses: front, back, and three-quarters. This in turn produced a three-dimensional effect of the image. While Athens was the main producer of red-figure pottery, it did spread throughout the Greek world, especially to southern Italy.

The development of art during the Greek period shows the evolution from mere two-dimensional stick figures to complex, three-dimensional works portraying the human body as it really looked. This progression of art allowed the continual growth of Greek culture, and during the Classical Age, the idealistic forms clearly were displayed.

Date added: 2024-08-06; views: 401;