Defensive structures in Ancient Greece

During the pre-Classical and Classical ages of Greece, military conflicts were usually decided on the open field, with battles fought by hoplites. A battle would often determine not only the military outcome of a situation, but the political outcome when one side achieved victory and the defeated acknowledged it. Often a side would avoid conflict by retreating into its fortified city with the plan to withhold a siege.

During this time, the sophistication of the offensive side was often limited to scaling ladders, sappers, and battering rams. The defensive side was often in a better position, especially if there was plenty of water and food. The defensive force typically had a superior rating based on its protected strength and ability to resist frontal assaults.

Before 700, there were few well-fortified sites, perhaps no more than fifteen, which could be added to the few preexisting Mycenaean forts that were now reused. During the period from 700 to 550, the number of fortified sites increased and included important cities such as Argos, Corinth, and Athens. The largest increase in defensive cities occurred after 550, which probably reflects the change in warfare from local tribal raids to more organized armies using the hoplite system. These forts would often be placed at strategic sites within the city, overlooking a fertile plain, an important crossing, or a port.

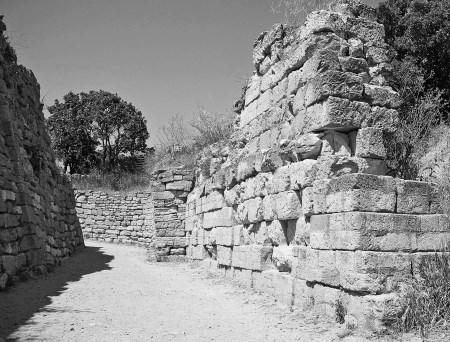

City wall and gate at Troy

A typical city had a citadel or protected spot built on a high hill known as an acropolis. Some cities such as Athens and Corinth had high peaks, which provided even more protection. This system allowed defenders the ability to hold the high ground, allowing them to fire further and see farther then on a level plain. In addition, attackers would have to expend more energy moving uphill. For some cities such as Athens, where the acropolis was on a fairly high hill, the terrain to reach the heights would be problematic, which gave the defenders even better resistance.

A city might have a wall protecting it. These walls were usually made of ashlar blocks of stone fitted tightly together to prevent movement and allow a stronger bond, or less commonly of mud brick with clay. The stones were usually large to prevent easy dislocation. These walls may have been as much as twenty-five feet high and twelve feet thick, and they would have been able to withstand the siege forces of the time. During the late Classical period, cities added towers to the walls, usually round or multiangular, which added to range and allowed covering for an adjacent wall.

If a city had a wall, it was almost impossible to take by storm. Evidence indicates that if such a city were taken, it was often because the attackers would use ladders to scale the wall. Occasionally, the attackers would look to alter the natural landscape, such as by changing the course of a river or stream so as to hit the wall head on to weaken it, especially if it were made of mud brick, or to dam up a river to flood the region or prevent water from reaching the city. The other method for taking a city centered on starving the besieged. If the attackers could come upon a city and its inhabitants quickly to prevent the stockpiling of resources, they might be able to starve them out.

City walls were symbols of independence and power. If a city lost a war or even a battle, its walls were often torn down, not only to diminish its military defensive power, but also to diminish its political power.

Other types of walls were also constructed for defense. For example, the Pho- cians built a wall across the small pass at Thermopylae to prevent the northern Thessalian tribes from attacking from the south into the region of Phocis. King Leonidas rebuilt the wall to prevent the Persians from passing through in 480; he was able to hold out for three days until his forces were circumvented and attacked from the rear. The battle and these tactics show how a strong wall could act as a barrier to prevent a frontal attack.

The most famous defenses were at Athens. During the Persian Wars, the old Acropolis walls, made of wood, had been burned. Afterward, the Athenians under Themistocles decided to rebuild the city walls. They realized that the city needed protection not only from a possible return of the Persians, but also from the Spartans if they wished to attack.

The city walls were built quickly and to a sufficient height to ward off any attack. For the next forty years, the Athenians transported supplies and goods between the city and the port at Piraeus five miles away without any walls and were exposed to possible attack. To counter this, and due to fighting occurring across Greece and the Aegean between 465 and 458, they decided to ensure the protection of Athens by fortifying the region between the harbor and the city by building a series of walls called the Long Walls. The Long Walls were then built between 465 and 445.

These walls, about three to four miles long, were made of stone from the local region. There were several walls in the system; the first was the North Wall, which ran four miles, from southwest of Athens to northeast of Piraeus. The second was the Phaleron Wall about three miles long, which ran southeast of Athens to the old port at Phaleron, which therefore blocked access from both sides to the harbor at Piraeus.

During the 440s, the Athenians built a parallel wall to the North Wall, often called the Middle or Southern Wall, which provided a more protective direct corridor to the Piraeus. It probably was meant to provide a backup to the Phaleron Wall. There was room between the North and Southern Walls for a large number of people to live on and even cultivate the land in the surrounding region. Since the Phaleron harbor had begun to diminish in importance during the 450s, the Southern Wall was crucial to protect Piraeus.

The harbor at Piraeus was further protected with its own fortifications, and in 429, Athens built a stronger defensive system there featuring towers and platforms to aid in repelling any direct attack. It also added moles, which created a barrier, and chains across the open part that could be raised to close off the harbor from ships, as a further protection, a common system at these times.

The purpose of the Long Walls, together with the walls at Athens and Piraeus, was to create a protected space secure from a land invasion so that Athens could receive supplies from the sea without fear of being cut off from the harbor and fleet some four miles away. This became even more important after the Spartans occupied Decelea in Attica in 413 and a Spartan army became encamped on Athenian soil.

This act prevented Athens from cultivating the area around it, forcing it to rely even more on the sea for its food. The Long Walls held out against Spartan attacks during the Peloponnesian War, but after its ultimate defeat in 404, Athens was required to tear them down. Athens would rebuild the walls in 395, and by 391, they had become part of its defensive system again, but over the next three centuries they were never used.

The defenses of Greek cities centered on having fortifications and the ability to withstand an initial attack. If that succeeded, the defenders often were able to remain safe, so long as they had sufficient supplies. It was only if supplies ran low or if the city was betrayed that it was taken. These walls did succeed for as long as the Greeks were facing each other with limited cities and resources, but they often failed against larger empires and kingdoms such as Macedon and Rome. Interestingly one of the cities that did not rely on walls for their defense was Sparta, which for many years withheld attacks with only their army.

Date added: 2024-08-19; views: 426;