Geography of ancient Greece

The geographical regions of Greece varied greatly and contributed to the unique position of the Greek city-states. The area was dominated by mountains and valleys, as well as bays and gulfs that created islands, isthmuses, peninsulas, and other outposts. Greece had completely different features from other peninsulas in Europe, such as Spain, Italy, and Illyricum; it was not a square like Spain or a wedge like Italy. Illyricum is similar to Spain, but without Greece attached as an appendage.

The most notable feature is the Gulf of Corinth, which effectively divides central and southern Greece into two parts, creating in essence the island of Pelops, joined to the rest of Greece by a narrow isthmus. The Gulf of Corinth gave access to the sea by otherwise inland regions on both sides, as well as making the coastal lines even more pronounced. Likewise, the Aegean Sea in the east created connections and hindrances for the Greeks. On the one hand, the sea allowed easy access to the islands and then to the western coast of Asia Minor, while on the other hand, it created a deterrent for easy movement requiring ships.

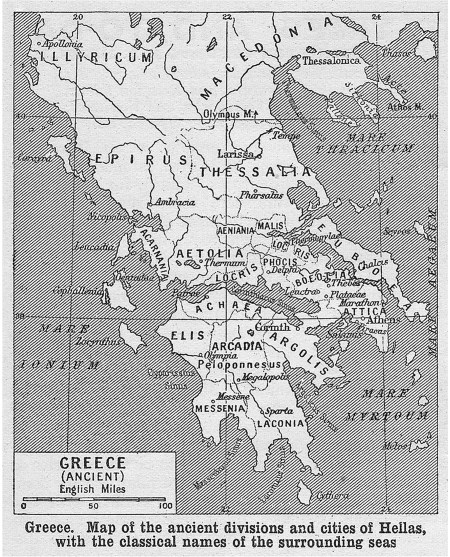

Regions of ancient mainland Greece

The Greek world can conveniently be divided into four major regions, each with subdivisions. The major regions were mainland Greece, the Greek islands, Ionia or Asia Minor, and the west, which included modern Italy, North Africa, and southern France. These regions not only interacted with one another, but with other non-Greek regions. In all of these regions, the Mediterranean Sea played an important factor in their development and peculiarities.

The Mediterranean provided means of transport between all of these regions and produced a moderate climate with hot, dry summers and cool, wet winters. This climate allowed enough rainfall for a variety of farming, usually not involving irrigation. As one moved away from the sea, the climate became less moderate and even, with temperature and humidity variances, and extremes with summers often becoming hotter and the winters colder than the coastal areas.

The Mediterranean region is ringed by a series of mountains that break the lands into small units easily isolated from one another. Although not terribly high, and usually not maintaining snow on them during the summer, the mountains created flat lowlands capable of farming, with higher lands more associated with forests and shepherding. These forests had an abundance of wildlife no longer seen there, such as bears, wild boars, lions, and even pigmy hippopotamuses. The area is geologically unstable due to tectonic plate movement producing earthquakes and volcanic activity. Although most ancient Greek literature dealt with cities, wars, and politics, the hinterland often influenced society more than usually recognized.

The mainland can be divided into upper, middle, and lower Greece. The upper region creates the main peninsula, where water surrounds the land on all three sides and has over 70 percent mountains. These mountains not only created trade problems, but also isolated many communities so that they developed into small city-states supported by the limited amount of land. The mainland is also lacking large rivers, which made travel within the hinterland even more difficult. These problems led to Greece being politically fragmented.

The upper or northern part of Greece contained the Pindus Mountains, which separated the region into two main areas, Thessaly in the east and Epirus in the west. Thessaly was the largest plain, with mountain peaks such as Olympus and Iolkus. In the west, Epirus was mainly a mountainous region that was often viewed by the Greeks as only semi-Greek. Thessaly contained the Aeolians, so named for the region’s name during the Homeric Age.

The great plain of Thessaly stretched from Mount Olympus south to the Spercheios Valley, with its river flowing into the Malian Gulf near the Pass of Thermopylae and about ten miles south of Lamia. This region produced cereals and other grains and allowed horse-rearing. The region produced several city-states and occasionally was controlled by one kingdom, but usually not for long. One of the most famous kings was Jason of Pherae, who ruled just before Philip II of Macedon during the 370s.

Middle or Central Greece represented the region south of Thessaly to the Pelo- ponnese. This narrow region contained areas such as Boeotia, with the city of Thebes; Aetolia; Attica, with Athens; and Acarnania. Acarnania in the west lay along the Ionian Sea west of Aetolia and was the entry into the Gulf of Corinth.

This mountainous region was made up of smaller villages in the Acarnanian League, usually united against Corinth, which had taken many of their best ports as their colonies. To the east lay Aetolia, where the Achelous River formed its western boundary with Acarnania. Lying on the north of the Corinthian Gulf, the Locrians in the east were their neighbors. This region was also wild and fiercely independent. They did not participate in the Persian Wars, although they vocally supported the Greek cause, and declared their neutrality during the Peloponnesian War not taking sides with either. When Athens attacked in 426, the league successfully pushed it back.

East of Aetolia was Locris and Doris to the north. Locris, also called Ozolian Locris or Western Locris, was not only mountainous but mainly unproductive. The most important city was Amphissa and its port at Naupactus, on the Gulf of Corinth. Thucydides mentions Amphissa for the first time, indicating that it was a semi-barbarous tribe resembling the Aetolians and Acarnaians. After the Aetolians pushed Athens out in 426, they submitted to the Spartans.

Doris, to the north, claimed to be the original home of the Dorians. The area lay between Mount Oeta and Parnassus and had the Pindus River flowing through it. It was a small area with four towns. The region submitted to Xerxes and the Persians. It was a member of the Delphic Amphictyony and was a strategic area leading to the north. Phocis, with the city of Delphi, lay east of Locris and Doris and west of Boeotia. The Parnassus ridge divides the region into two districts. Although the region did not have natural wealth, it did claim the Delphic Oracle and derived much of its importance from this religious site. When the Persians attacked, they at first helped the Greeks at Thermopylae (480), but with their defeat, they were taken over by Persia and fought the Greeks at Plataea the next year.

To the east lay Boeotia, with its important city of Thebes. Although it lacked good harbors, the region was crucial as the intermediary between Thessaly and Attica. Unlike Athens, which incorporated the towns of Attica into its political system, Thebes could not achieve this same result with its outlying cities. Although during times of crisis, the cities came together in a united defense, unlike with the Arcadians, their constant distrust of each other did not allow much cohesion. During the Persian Wars, Thebes sided with Persia. Sparta supported Thebes in its efforts to resist Athens during the 450s, and although Athens briefly controlled the region, Thebes fought Athens during the Peloponnesian War. After the war, Thebes broke the power of Sparta and became the prominent power in Greece. Its loss at Chaeoneia to Macedon ended Greek independence.

The remaining area of Central Greece was Attica and Megara. Attica is a triangular peninsula, with the Cithaeron mountain range separating it from Boeotia in the north and in the west with the narrows to Megara and into the isthmus to Corinth. Attica had plains rich in agriculture and mountains, which produced silver. Athens, its chief city, was able to unify the entire region under its control by the fifth century. The western coast of Attica lies along the Saronic Gulf’s eastern coast. The Aegean forms the eastern termination of Attica, with Cape Sounion as its tip. To the west lay Megara, which was north of Corinth. It was the capital city of the Megaris, a small but populous region linking Central Greece to the south, the Peloponnese. The region originally controlled the island of Salamis, but it was lost to Athens in the seventh century.

Southern Greece, or the Peloponnese, was another mountainous region. It consisted of Corinthia in the northeast, coming from the Isthmus, and Megaris, with Corinth as its chief city; Argolis in the east, jutting out into the Aegean, with Argos as one of the driving forces; Laconia in the southeast, with its broad, fertile plains, which was controlled by Sparta; Messenia in the southwest, with its plains and hills, which was put under the control of Sparta early and whose population was enslaved, creating the helots; Elis in the northwest, fronting the Ionian Sea with Olympia; Achaea, in the north between Elis and Corinthia on the southern coast of the Gulf of Corinth, with its confederation of twelve cities led by Patras and Dyme; and in the interior, the mountainous region of landlocked Arcadia, with its cities of Mantinea and Tegea.

In the Aegean, the islands of the Cyclades make a circle around Delos, the ancient sacred island, providing a link between the mainland and the western coast of Asia Minor. Associated with their early history was the large island of Crete in the south, with its Minoan culture based at Cnossos. To the southeast of this line of Greek islands lay the large island of Cyprus, which became the point of interaction or the melting pot for Greek, Phoenician, and Asia Minor. During the Classical Age, most of the islands were allied with Athens through its Delian League.

Farther east lay the important region of Asia Minor, also known as Anatolia, which included many Ionian cities, as well as cities to the north, which were Aeolian, and in the southern part, which were Dorian. The coastal region had numerous Greek cities, which naturally looked to the west and Greece rather than to the east and their landlocked regions. These cities were the colonies that were established during the Dark Ages, and which in turn established colonies on the coast of the Black Sea to the north. They were conquered by the Persians in the sixth century and earned their freedom during the fifth before being conquered again by Persia in the late fifth to early fourth centuries. Chief among these cities included Miletus, Ephesus, Chios (an island off the coast), Smyrna, and Samos (an island off the coast).

Finally, the western colonies of Greece, primarily from Corinth, were established. Beginning with Corcyra off the coast of western Greece, Corinth established a series of colonies in Sicily and southern Italy. The chief city was Syracuse, and others included Gela, Akragas (Agrigento), Selinunte, and Zancle in the west. These colonies made contact with Carthage in North Africa and the Etruscan cities in Italy. Associated with the colonies in Sicily, the city of Cyrene in Libya, established by Thera, provided connections with both Egypt and Carthage on the northern coast of Africa. In southern France, the city of Massalia was founded by colonists from Phocaea, a Greek city on the coast of Asia Minor.

The Greek world, therefore, was a complicated system of city-states distributed across the Mediterranean. These entities provided a way for Greek culture, which was not homogenous, to spread throughout the region and influence other societies. As for the Greeks, they never lost their identity as residents of small city-states in mountainous regions close to the sea. Their colonies tended to be located in coastal areas, reviving their native geography.

Date added: 2024-09-09; views: 449;