Planning Composition into Your Curriculum

Imagine a middle school music teacher who directs orchestra, band, and guitar ensemble classes. He began incorporating composition after being challenged with the prospect of doing so during his graduate degree in music education. Initially he used plans from other teachers, and then eventually started designing his own composition lessons. His key to success was not simply the lesson ideas, but the actual planning of the composition sessions into his monthly teaching schedule. Teachers can read books, attend workshops, and compose pieces as preparation for teaching composition, but none of those will matter if the key elements of the times and dates are not put on the calendar.

There are as many ways to include composition lessons into a music curriculum plan as there are teachers. Some teachers like to plan a four-week composition unit during January and February each year, and as a follow up, selected students participate in a young composer festival at the end of the school year. This plan gives students time to establish social relationships, build trust and gain the requisite skills and knowledge during the fall semester. Composing requires students to be brave enough to share ideas that their peers might be critical of, so an atmosphere of collegiality and respect is important to have established. January also seems ideal because it is before the busy spring festival season or performance pressure build-up, and compositions can even be used for solo and ensemble festivals, not to mention composition festivals. Other teachers prefer to plan a short lesson once a week and spread the creative projects throughout the entire year. Additionally, using the last few weeks of school to work on composing projects can be ideal if there is down time after performances, and students are ready to try out something different and creative. Another consideration is to put some dedicated lesson time in at the beginning of the year, and then, offer short composition assignments throughout the year. A final consideration is to identify a young composer festival or showcase or plan one for the school district and plan your composing lessons to culminate in time for the festival.

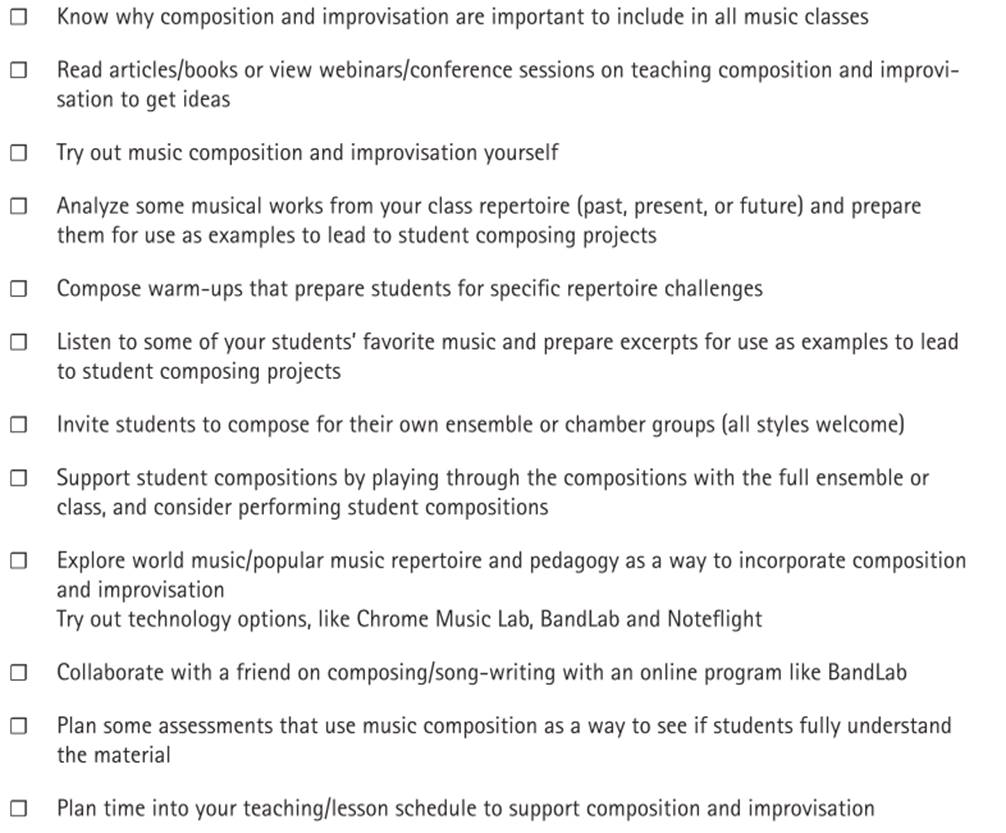

Conclusion. There are many pathways that may be taken to reach the ideal of a creative classroom. Music teachers looking to walk this path may find it helpful to consider the checklist in Figure 7.3, which summarizes many of the ideas presented in this chapter.

Assessment, books, songwriting, music technology, and other approaches represent a few of the pathways we have at present—and more options will follow. Regardless of the pathway that teachers select, the key is to take the first step. Try one or two small creative music-making activities, and then continue to purposefully schedule composition into classes so it becomes a normal part of teaching and learning. There

Figure 7.3. Checklist for starting music composition is no “one” way that music teachers journey into the areas of teaching composing, just like there is no “one” way that composers begin composing. What is important is opening the door for both teachers and students to begin their creative adventure. Music curricula that provide students with opportunities to explore and develop composition and improvisation skills and interests can produce life-long learners and musical artists who think creatively and empathetically, no matter what career field they may choose to pursue

References: Aardema, V., Dillon, L., Dillon, D. (1975). Why mosquitoes buzz in people's ears: a West African tale. Dial Press.

Adolphe, B. (2020) The mind’s ear: Exercises for improving the musical imagination for performers, composers, and listeners. Oxford University Press.

Agrell, J. (2007) Improvisation games for classical musicians: A collection of musical games with suggestions for use. GIA Publications.

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). Taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives, Abridged edition. Pearson.

Anderson, W. T. (2012). The Dalcroze approach to music education: Theory and applications. General Music Today, 26(1), 27-33.

Aston, P., & Paynter, J. (1973). Sound and silence: Classroom projects in creative music. Cambridge University Press.

Beegle, A. C. (2001). An examination of Orff-trained general music teachers’ use of improvisation with elementary school children. (Catalog number 05A 2026). Master’s thesis, University of St. Thomas. Master’s Thesis International.

Bell, A. P. (2020) The music technology cookbook: Ready-made recipes for the classroom. Oxford University Press.

Blackshaw, J. (2014) Earthshine. Notes to the Conductor. Wallabac Music. https://13071e95- 4bdd-97a4-0fb3-f67f59071d85.filesusr.com/ugd/b8e057_5ad2b1af57af48d6978458d865ce8 e73.pdf

Date added: 2025-03-20; views: 285;