Pedagogical Underpinnings for Music Technology

The ultimate goal of this chapter is to provide the pedagogical and technological foundation for engaging students in music creation and composition. With a focus on informal and non-formal learning, I will suggest approaches similar to those of Computer Clubhouses, developed by researchers from MIT’s Lifelong Kindergarten group. These clubhouses were developed to facilitate students’ interests in computing by allowing students to set their own goals. Embedded in this framework is an emphasis on project-based, informal, and participatory approaches to learning at its core, involving sharing and collaboration with few obstacles to artistic expression. In Lifelong Kindergarten, Resnick (2017) discusses his philosophy of technology creation with regard to what Papert2 refers to as high ceilings and low floors.

What this means is designing the technology to allow novice users easy entry into working with the software. In other words, the low floors metaphor is about creating user-friendly technology without a steep learning curve. Yet the high ceilings is the technology’s ability to provide a structure for users to develop greater sophistication and complexity in their work as they become more experienced. With regard to the Computer Clubhouses, Resnick adds the caveat of also including wide walls in the design of technology. Resnick (2017) states the objective of the wide walls comparison is to design the technology to encompass a wide range of interests and pathways to achieving one’s goals.

The potential for growth and complexity within this environment is limited only by one’s imagination, and as suggested by Peppler (2017b), allows for the development of interest driven expertise through exploration, trial and error, peer-to-peer collaboration, feedback, and mentoring. With a minimum of technological expertise and expense, setting up a class environment that allows for open ended excursions into playing with and manipulating sound as entry points into composition will yield higher levels of student engagement and interest.

The computer clubhouse supports project-based learning to connect students to learning through activities they find personally meaningful (Brennan et al., 2010; Peppler, 2017b; Resnick, 2017; Rusk et al., 2009). Another feature is the collaborative, open-ended approach that is less teacher-directed and is framed by a more constructivist approach to education (Jones, 2017). This approach supports the development of critical thinking and problem-solving skills and encourages students to not just consume and interact with technology, but to be creators. As with music teachers who wait until their students know traditional notation before letting them compose, Resnick (2017), believes many educators are wary of project-based learning, fearing that one needs to first teach the basics before students can work on projects. Yet his research emphasizes that project-based learning can provide meaningful contexts for students to interact with concepts and apply what they are learning in other areas as well.

Teachers who adopt a clubhouse approach to student engagement and interaction, would need to employ informal and non-formal learning approaches that are participatory in nature, allowing students to investigate and explore their creative ideas more in depth and build on the social interactions that are ever present in students’ lives (Jenkins et al., 2009; Martin, 2017; Peppler, 2017b; Turino, 2008). In addition to learning to code in Scratch, which is web-based, (Brennan et al., 2010; Resnick, 2017; Rusk et al., 2009), there is a very robust online community.

The Scratch website is set up much like a social-networking site so that students all over the world can share their ideas and their projects, as well as give and receive feedback on their work. The peer-to-peer mentoring that takes place in music clubhouses and within the online Scratch community, along with the access to music and media technology, supports the goals of today’s students for sharing and creating music with one’s peers (Kenny, 2016; Tobias, 2015; Waldron, 2012). Music technology, whether it’s as a tool, medium, or instrument, makes it possible for students to pursue the music that interests them, lets them connect with their peers on a social level, and provides a sense that what they are doing matters (Jenkins et al., 2009; Tobias, 2015).

Informal learning practices in music, popularized by Lucy Green in the United Kingdom through the Musical Futures Project is based on the intuitive practices employed by popular musicians (Green, 2001, 2006, 2008) and (Peppler 2017a). Students decide what music they want to learn using their ears and intuitive music knowledge, without much outside intervention or reliance on formal notation. With a non-formal approach, the programming is a bit more structured by adults, though students can help to determine their individual goals. The role of an adult in this approach is to be more of a facilitator (Peppler, 2017a; Smith, 2017). In the Musical Futures model students are tackling the learning of the actual music they are hearing out in the world, as opposed to the often-simplified compositions that are the stock and trade of many school music classes and ensembles (Peppler, 2017a).

Composing with music technology is a way for students to get really close to replicating the music they are growing up with. With its ability to provide instant aural feedback along with many of the effects processors and tools artists use, students can easily alter instruments, harmonies, and melodic versions, based on what sounds good them. Green’s (2001, 2006, 2008) research suggests the informal learning approach utilized in the Musical Futures project helps increase school engagement of disaffected youth through participation in music study. It should be noted, as Green points out, that in a typical informal, out-of-school context, students work at learning the music at their own pace without the pressure of formal assessments.

One of the earliest developments in music technology for young children was based on the underlying premise of Jeanne Bamberger’s groundbreaking work in music cognition, and her research into musical intuition, particularly with regard to musical hierarchy and form. (Bamberger, 1979, 1995, 1996, and 2000). Her research into students’ perceptions of how music works, how melodies are structured, and what gives music coherence began with the creation of a game through a Logo Music3 project she called Tuneblocks (Bamberger, 1979). It is one of the earliest interactive computer programs for young children that allowed them to manipulate the materials of music, rather than drill them about music. It helped students make sense of the music, not as notes but as motives, figures, and phrases, and provided immediate aural feedback.

Her work with Logo eventually led to the creation of Impromptu4 in 1999, as a digital music platform that encourages students to actively build their knowledge base through analyzing simple tunes and creatively developing their own musical understandings. This software is divided into five discrete “playrooms” for melody, rhythm, harmonization, four-part harmony, and rounds. The two most prominent ones are Tuneblocks for melody, and Drummer for rhythm. In the Tuneblocks playroom, students are asked to reconstruct simple folk melodies by putting the blocks containing musical phrases in the correct sequence, in order to reconstruct the tune. They are then asked to think about how the tune is constructed, which blocks are repeated and why, as well as the function of each block; which is a beginning, middle, or end (Bamberger, 2000 and 2003).

Students can open the individual blocks to see and learn about pitch and duration properties. They edit them based on a variety of scales and modes. In addition to traditional folk tunes, there are several melody playrooms that feature music from a variety of cultures,5 as well as ones that feature music with no tonal center. The program also allows students to remix melody notes and rhythms within the blocks, as well as altering the tonal system for each block.

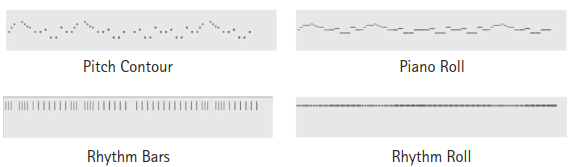

The Drummer playroom allows users to employ everyday mathematics to understand the structures that organize music rhythmically through ratios and proportions. Another feature of this program is its ability to let users access multiple representations of detail such as pitch contour, piano roll, rhythm bars, or rhythm roll (see examples in Figure 14.1 for the tune “Lassie”). There are many activities that can be accomplished with the Impromptu software, which can be found on the software’s website at: http://www.tuneblocks.com and at https ://makingmusicco unt.org.

Figure 14.1. Graphic representation of the tune “Lassie” in Impromptu

The concepts embedded in Jeanne Bamberger’s Impromptu will be further expanded upon in this chapter with the Interactive Puzzle Card Activity, which helps students to think about and explore how music is structured.

While these more exploratory informal and non-formal approaches to learning and assessing are often at odds with the way in which school-based classes are structured, the benefit of these approaches is that students are composing, improvising, and immersing themselves in a great deal of deep listening and musical analysis. Perhaps through the development of open-ended projects that are personally meaningful to students, teachers can find the right balance for engaging students, while including some form of peer and self-assessment in the grading mix. Would they share their creation with their friends or post it on YouTube or SoundCloud? Why or why not?

Date added: 2025-03-20; views: 264;