Resonant Spaces for Composing in the Classroom—De-centering Music

To place the ideas and concepts discussed above in practical terms we sought the insight of several practitioners working in the US and Canada who have nurtured the dispositions toward and experiences enacting the kind of policy practice we argue for in this chapter. Below we highlight the insight, expertise, and practices of teachers doing this work, today. We present these in the form of three cases across middle and high school and university in general, choral, and wind ensemble.

Composing as Non-negotiable. Joanna is a Canadian middle school teacher with near 10 years of experience. Her background is rather traditional, as she says, but was marked by a positive experience with a co-curricular program called School Alliance of Student Song Writers. At a time where her training and previous experiences were proving somewhat limited, particularly in relation to her efforts to reach more students and to engage them fully, the Alliance, a network-based, district-led, cross-school program, created both a space for professional development and curricular re-imagination.

Central to her efforts, and those of the Alliance, was the idea of providing a curricular space that would “give the students the opportunity to create themselves”—the double entendre being intentional. Joanna spoke about the fact that once she became part of the program and brought it to her own school, her aims shifted from delivering content and teaching concepts, to “applying the musical concepts in the creation of new material.” As she articulated, “once I saw that as possible . . . once understanding became key, it was not enough that they [students] simply reproduce, play the work of others.”

Following the parameters discussed here, composition was understood broadly by Joanna, where the aim of musical learning was a process where scaffolding was variable and where movement, singing, instrumental playing were precursors to, and found their way into, creating. This led to a “change in my teaching” with new commitments articulated thusly, “I really saw this moving forward, for me, when I made the program and what it offered as a non-negotiable.”

Joanna’s story speaks of a shift from big P policy to small p policy practice—policy know-how in motion. She spoke clearly about the need for catalysts to enact the program, how she benefited from the program history, the network of teachers who helped her, and the district-wide support for the program existence. Framing the relationship between wider support and personal policy commitment, she articulated the linkage between the elements, the catalysts, that together meant implementation was possible and sustainability was attainable (the program has over a decade). The circle went: people, structures, program, practice, people—with commitment, in all levels, being key.

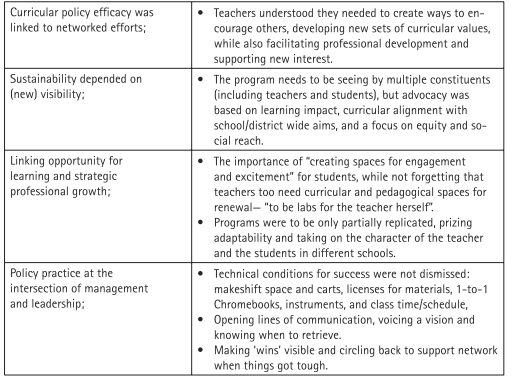

Without articulating any policy theory—or really uttering the word—Joanna talked about central policy practice dispositions (see Figure 42.1) that made the program and a new curricular vision succeed.

Figure 42.1. Joanna’s observations

While there are many lessons here, the articulation that this new venture led Joanna to re-think the role and place of creating within the learning process is key. This was not simply a manner of adding a potential “standard” of practice; it was not simply about “aligning with state curriculum requirements.” Rather, it was a welcomed opportunity to teach differently, to create a “community of song writers” and provide a “creative connection between challenges in our [hers and students’] lives" We interpret the decision to make composition as a manifestation of certain educational values and a non- negotiable, as a moment of policy enactment (Ball, Maguire, & Braun, 2012); the leap into a new professional practice and an engagement in the politics of doing what was necessary to see the vision through. This was a moment of taking ownership as well, as Joanna articulated, establishing her personal policy practice, seeing herself critically engaged in the continuum between “other peoples’ objectives and my own objectives"

“When We Gonna Change?”. Some high school choir directors may “exclude composition" thinking it antithetical to “expectations and pressures of ensemble teaching" Indeed, “external authorizing bodies" and internal and ingrained beliefs (i.e., convenient knowledge) can and often do de-l egitimize student composing, especially in ensemble settings where products are practiced to perfection and then to performance. However, as this Chicago high school choral director has articulated and successfully shown, “Composing can enrich the ensemble classroom, create a stronger sense of community, [and] create more skillful musicians" For Casey, his disposition toward composing in the choral classroom began to shift during his undergraduate years, specifically in his Philosophy of Music Education course where he was asked to think about: Who is doing the creative work? Who is the creative person in ensemble settings? Casey’s high school initiated a co-curricular program called Colloquium Day whereby students can register each semester for a variety of curricular activities, a “non-traditional space” that nevertheless functioned well “at the periphery of core subjects.”

This led to a songwriting course and a secured partnership with a local organization called CAPE (Chicago Arts Partnership in Education). Paired with poet Ladan Osan, Casey and the colloquium students (some choir members, others not) composed original pieces expressing their views of a city that had come under fire as the “national punching bag of Donald Trump” In these compositional activities students could sound out “how they hear and see their city” reinforcing how students are capable of being creative and critical, and could and should do so in the choral classroom space.

One opportunity came during the height of district budget cuts. The students at his school would be disproportionally affected as a result since “the State funding system was known to be the most inequitable in the country.” He decided to invite choral students from across his choirs to compose a piece addressing this issue. His choristers had already been introduced to “protest songs and music from Apartheid South Africa” so he encouraged them to consider how their own song could express their frustrations and fears. The outcome, the song “When We Gonna Change?” garnered critical acclaim across news stations and media outlets in Chicago and was performed at a rally in front of the Chicago Board of Education. The following year, other choristers joined and composed a sequel: “Which Side Are You On?” They took this song on the road to the state capital of Springfield where they performed on the steps of the governors’ headquarters to a body of legislators.

Casey said, Students were composing what reflected their identity, creating original work, creating for an authentic audience Not just a school choir concert, this was a performance that got media attention, [with] politicians watching the performance. . . . Composition created an opportunity for students who may have never considered themselves someone who had the talent or wasn’t special enough that they have that kind of platform We [could] just totally change how a young person conceives of themselves.

Duet for Heart and Breath. For Dr. S, facilitating spaces for her students to be creative is paramount. She feels so much of musical training can “deaden” creative processes, particularly as it relates to composing where “students are told, you can’t break the rules until you know what the rules are . . . [and] you have to pass through all these gates before you’re allowed to be creative, by the time you get there you’ve internalized that you don’t have any creativity.”

Seeing this as “a tragedy" she encourages her students to listen and collect sounds from their environment and use these in composing original pieces. This she does not only in her mixed-majors course on social justice arts education, but equally significantly with her traditional wind ensemble students. At a recent honors festival, one of the university’s major “recruitment events" she wondered how she might facilitate an activity for “students to feel connected to one another even though they are in two separate bands and create something together" Realizing that both ensembles’ repertoire “dealt with the notion of ‘what is home’ and why is home important, and what happens when your notion of home is shaken" she asked the 100 performers (including many international students) to record sounds related to their conceptions, experiences, and memories of home. Scored for large ensemble and set against ambient melodic passages all students could play, sounds of “trains, washing machines, pets snoring, and the jingle of mother’s bangle bracelets” and many others filled the auditorium. Dr. S recalls, “Students listened smiling as their sounds filled the air. . . . at the end of the performance the hall was so quiet you could hear a pin drop. . . . It was a surprisingly moving experience. . . . [There was] a sense of unity between students, audience, and conductors sharing and connecting in that moment through sound"

What Joanna, Casey, and Dr. S have in common is their commitment to providing spaces for their students to actively re-engage and share their voices through a creative medium such as composition. Whether in general music classes or traditional ensembles, student voice can lead to student agency, which in turn may lead to the kinds of inclusive, diverse, equitable, culturally relevant, responsive, sustaining, and just pedagogies many music educators today aspire. More than just an activity, however, or tool, composing showed itself as indispensable curricular aims inviting and celebrating “creative expression and symbolic work” of students. Thus, cultural production was paramount to actualizing these teachers’ and students’ intentions. Another significant commonality shared between these three teachers has to do with their approach to music and so-called musical elements of composition. They created resonate spaces for composing in the classroom by expanding their view of and “De-centering music”—a philosophical and pedagogical practice that troubles “the Eurocentric origins of the word ‘music’ [and] unseats music from its place of hegemony” (Recharte, 2019, pp. 69-70). Recharte further suggests,

This de-centering of music has the advantage of possibly enabling music educators to transcend the hierarchy of musical styles that organizes which sounds are deemed more musical than others and avoid some of the problematic requirements of traditional music education. (p. 82)

Ordinary conceptions of composition, composing, and composers are entangled in a problematic paradigm of cultural objects propagating colonialist patriarchal dos-and- don’ts (Cox, 2017). If composition is to move beyond the periphery and into the core of curriculum policy and practice, then re-evaluating terms and concepts born from such music ideals is critical. We argue that a decentering of music is already present in the practices of these teachers, and also of many others. This current handbook is a testament to the field’s commitment to reframing pedagogical sensibilities around music/sound (Rice & Clements, in this volume, “Developing Soundcrafters: Facilitating a Holistic Approach to Music Production”), aesthetics, originality, and genius (Smith, in this volume, “Vocabularies of Genius and Dilemmas of Pedagogy”), for example. Powerfully, they show that ultimately it is the combined sensibilities of teachers and their students to tune in and listen deeply to their “Sonic Commons” (Odland & Auinger, 2009). By opening their ears, hearts, and mind to sounds informing and impacting their lives, and responding by sounding out their individual and collective creative critical consciousness, these teachers and their students challenged long-held assumptions about what constitutes music and thus, composition.

Date added: 2025-04-23; views: 255;