The Role of Music Teacher-Educators in Re-Centering Composition

With equal seriousness one might ask, “Where does the work of music teacher education begin?" and perhaps with an added measure of exasperation, “Where does the work of music teacher education end?” In consideration of the latter, it is easy to teach the longstanding and familiar, comfortably settled into a body of information masquerading as sufficient. Such practices absolutely mark the end of music education. It is in the answer to the former question, however, that the future lies. Music faculty constitute a body that must be committed to further educate itself if it is to keep pace with societal and musical evolution and prepare future generations to do the same.

Self-Education. In the 1980s and 1990s, practitioners and music teacher-educators could reasonably argue that few resources existed to address music composition in compulsory schooling. This is no longer the case. Research examining the compositional processes and products of children grew significantly across these and the following decades.

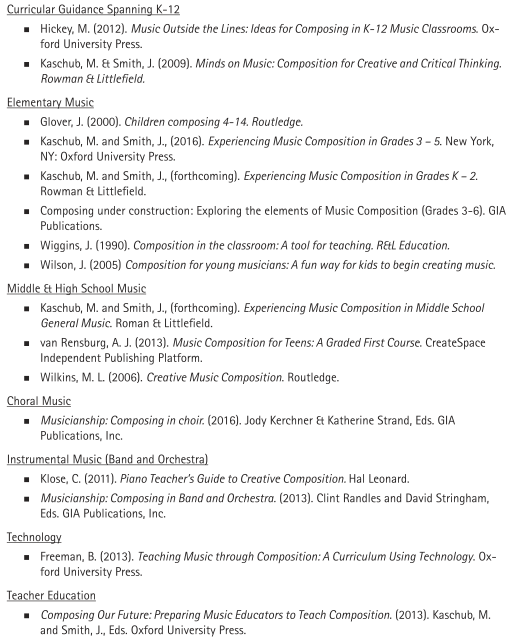

These efforts brought forth a considerable collection of books and articles offering insights about the work of young composers as well as guidance for teachers seeking best practices across a range of settings. Entry into this literature might be found through the literature reviews of Wiggins (2007), Kaschub & Smith (2009), and Viig (2015), or in the selected list of composition-focused books featured in Figure 43.1. In addition to written resources, state, division, and national conferences now feature programming devoted to composition. These topic area strands often address composition, songwriting, and production across a range of ages and settings so that educators might tailor their inquiries to match their teaching responsibilities.

Figure 43.1. Select books addressing composition and composition pedagogy

Addressing Curricular Challenges. Music teacher-educators analyzing current teaching practices and learning goals in PreK-12 education understand that there must be a link between those visions and the courses they design. In seeking modifications to existing curricula, they may encounter questions concerning why change is needed and exactly what changes should be made. These concerns require serious attention as curriculum represents how philosophical beliefs become realized within the boundaries established by accrediting bodies and specific institutions. Moreover, the curriculum that pre-service teachers experience in their preparation programs constitutes a lived curriculum against which they measure their future curriculum design decisions.

Teacher education programs are necessarily shaped by credit hour limitations, scheduling, faculty availability, enrollment, and dozens of other influencing variables. In terms of curriculum implementation, these areas constitute logistical hurdles which often can be overcome with a commitment to problem-solving. The bigger challenges lie at the level of fundamental belief systems and concern three important questions: Who can be a composer? What is the value of composition? and What can be considered core foundations in the preparation of music educators?

Reconceptualizing the Composer. Despite evidence to the contrary, many musicians—even college faculty—hold a vision of the composer as a solitary figure, possessing a special talent rarely found in the general population. This mythological image has led to a world in which children, when asked to draw a composer, sketch a man with long white hair, sitting at a piano, feathered quill in hand, notating their masterpieces (Glover, 2002). While there is hope that conceptions have evolved following Glover’s study, these ideas are so deeply entrenched within institutional practices that Campbell, Myers, and Sarath (2016) authored a manifesto arguing for the broad inclusion of composition within college music curriculums. This point cannot be made strongly enough: a manifesto was deemed necessary to advocate for teaching the very practice that brings music into existence. What music exists that does not have one or more originators?

To address the curricular marginalization and experiential exclusion that such beliefs have wrought, music teacher-educators must partner with composition and other faculty to design ways for pre-service teachers to gain personal and positive experiences in composing. These experiences must not be limited to the use of the instructional etudes that are often part-and-parcel of music theory coursework. While such activities highlight important historical practices and the foundations of modern composition, they are teacher-driven and limit students’ imaginations. For composing experiences to be powerful contributors to the development of pre-service teachers’ belief that they can compose, they must have artistic control over the design choices and musical decisions that shape their work.

The Value of Composition. As much of collegiate music study centers conservatory-styled education in the preparation of teachers (Kratus, 2015), questions arise concerning how composition can be used to develop musicianship—meaning to serve performance. This view is short-sighted. The value of composition is not limited to advancing performance knowledge and skills. Rather, the value of composition lies in its ability to allow people to communicate their musical ideas and imaginings rather than limiting their musical engagements to the interpretation and delivery of the work of others.

In this same vein, looping software and other methods of creating with technology are often attacked as being in some way lesser than real composition which is typically defined in the mind of the commentator as the use of musical notation of the European style. It may be possible to point out that these approaches require specific skills that take time to learn and develop, just like the forms of composition that predate these approaches. Additionally, while the tools used to carry out this type of composition differ from those used previously, looping and other production tools do require many of the same thought processes as the models as those found in earlier form of music composition.

Music Teaching: A Varied Vocation. Collegiate music education faculty, for the most part, have progressed through degree programs requiring the development of a particular set of performance skills associated with solo performance and participation in large choral or instrumental ensembles. While these requirements are certainly one way to prepare future music teachers, they are not the only way to do so. Other forms of music and musical practices seeking to enter the bastions of higher education face considerable challenges, primarily that they are outside the comfortable experience of those already inside the institutions.

As an example, for many years jazz was excluded from school classrooms and higher education (Mark, 1987). People preparing to become music teachers learned little, if anything, about jazz history - and they certainly were not allowed to specialize in its practice. Music teachers writing in response to the suggestion that jazz should be represented in music education programs in the United States offered derisive criticism:

Training a group of student instrumentalists to perform trite and transient music in emulation of some of the more pretentious professionals seen and heard on recordings, radio, and television is not a particularly good example of a worthwhile educational project. (Feldman, 1964, p. 60)

At present, jazz has been fully assimilated into most collegiate music programs. National accrediting bodies urge its inclusion in history courses, through ensembles, and in other areas of study. In some programs, music education majors can declare jazz as their applied area of study or as the primary concentration within their degree program. While this evolution has advanced knowledge of the jazz idiom, there are other musical forms and practices now standing where jazz once waited. Changing acceptance status requires a lengthy journey as evidenced by a footnote from Feldman’s 1964 work. Offering what he thought to be a seething condemnation of the popular music of the day, “rock’n’roll" he wrote, “It is, in effect, an oversimplified, primitive, and juvenile version of jazz” (p. 60).

Now modern band, hip-hop, popular music, and others are finding their way into tertiary music programs. These musical practices often are presented as topics of current interest rather than positioned as music education degree specializations or concentrations. Just as jazz once sat outside the comfort zone of music faculty trained and educated in other areas of music-making, so composition still sits. Recognition of the influences that shape the inclusion/exclusion conundrum suggest re-evaluation of the status quo. Composition, the activity that provides a foundation for the creation of much of the world’s music, must be intentionally and meaningfully included in preparation of music educators.

Date added: 2025-04-23; views: 220;