Composition Educators: Considering New Professional Identities

Identity is tied to the defining moments of life. It arises from experiences that inform and allow people to create themselves into purposeful, artistic, and expressive beings. Identity is a cognitive (Berzonsky, 2011), emotional, and embodied construct (Hodgen & Askew, 2007; Rajan-Rankin, 2014) that provides a personal frame of reference for processing self-relevant information, solving problems, and making decisions. It guides, and is shaped by, life’s journey (Kroger, 2007; Zimmer-Gimbeck & Mortimer, 2006) and finds definition in affiliations with social and professional groups (Brewer & Hewstone, 2004).

In totality, identity might be described as an understanding of self that is fashioned through discourse and derived from the categories in which people are placed and in which they place themselves. These categories may be real and culturally evident, but they are not natural; they are constructed (Hall, 1990). As such, it is important to consider identity in music teacher education. For example: What categories of identity exist? Can people freely choose their affiliations or are some choices limited? What influence might music teacher identity have on the practices of music education?

A Troubling Dichotomy. The history of identity research in music teacher education finds root in the concept of occupational identity. This term refers to the conscious awareness of oneself as a worker (Skorikov & Vondracek, 2011) and denotes perception of occupational abilities, goals, interests, and values. Investigating the development of occupational identity in music education majors, Froelich & L’Roy (1985) noted that pre-service teachers self-identified as performers more strongly with each year of study, though they could not readily identify the broader aims of music education. These findings raised concern about the focus and quality of music teacher education and spurred numerous studies probing the balance between “performer” and “teacher” (Ballantyne et al., 2012; Bennett, 2013; Bernard, 2004; Beyon, 1998; Bouij, 1998; Chong et al., 2011; Cox, 1997; Dolloff, 2007; Gillespie & Hamann, 1999; Haston & Russell, 2012; Hargreaves et al., 2011; Isbell, 2008; Pellegrino, 2009; Roberts, 1991; Scheib, 2007).

While many different facets of identity are now recognized in the literature, early studies upheld this initial dichotomy. Polarization can be useful in the early stages of problem-defining, but the maintenance of this particular dichotomy as it plays out in teacher preparation programs is an impediment to music education’s future. The problem is not that the dichotomy is unfounded, but that it was the only finding possible. Vocational aspects of identity develop during childhood and adolescence as preferences narrow (Beal & Crockett, 2010; Guichard, 2001; Holland, 1987; Savickas et al., 2009), and when children are presented with a singular option, preferences solidify very quickly. If school-age students are instructed by teachers who present music education as performance education while granting little attention to listening, composition, improvisation, and other musical engagements, those same students when seeking to become teachers will self-identify as performers (Rickels et al., 2013).

In researching music teacher identity, music education has led the witness and marveled at the troubling testimony offered as if it came as a surprise. The deck, if music teacher education can be so characterized, was stacked—and so it remains. Sociology’s focus on occupational identity has given way to a conception of identity that is multifaceted and increasingly nuanced. Yet, music education largely remains focused on a dichotomy of its own construction and validation while a bigger mystery remains to be solved: Where are other musical roles in the conception of music educator?

The Preservation of Dominance. In seeking to understand identity, sociologists have examined the evolution of dominant identities and how they are sustained. Over time, dominant roles acquire the appearance of common sense (Kumashiro, 2009) and thus remain unquestioned in practice. The application of objective interrogation to such practices often allows their roots to be better understood. For example, Kratus (2015) has traced a series of key influences that shape present practice throughout music education. First, in the European art music of the 1800s, the performer eclipsed the composer and captivated audiences with showy performances and dramatic flair. In response, conservatory training focused on creating more performers. When institutes of advanced study turned attention to teacher preparation, the model of performance training was already well-established and education a simple add-on. Subsequently, teachers translated their training into their work with school children to complete the trickle-down sequence.

The deeply entrenched performer role dominates nearly all areas of music education. Those who belong to this category wield considerable agency in maintaining their positions of power (Johnson, 2006; Kimmel & Ferber, 2010; Wildman, 2005). Dominant practices are insulated and protected through the construction of community-specific values, social classes, and other hierarchies (Goodman, 2011; Meyers & Gutman, 2011) and faculty whose primary musical backgrounds are in performance articulate and enforce the rights of entry and passage, as well as the rules of exclusion, for those seeking to join the ranks of music education. Entry-seekers and participants are limited to specified fields (performance) and instruments (often those of the Western classical tradition) along with their concomitant audition procedures, courses of study, and juried recitals. Every level of participation is designed to give senior level performers the opportunity to judge and approve or disapprove of all others—effectively enforcing a within-group hierarchy that completes the cycle of power.

“The Wages of Dominance Is Damage”. Damaged identities form when members of a powerful group view others as unworthy of full respect to the extent that less powerful groups are prevented from “occupying valuable social roles or entering into desirable relationships that are themselves constitutive of identity” (Nelson, 2001, p. xii). Within music teacher education the exclusion of would-be teachers who excel in composition—or at minimum, the requirement that they prioritize a performer-role, as is commonly the case—constitutes a “deprivation of opportunity” (p. xii). This prevents the profession of music education from developing a particular knowledge and pedagogy absent from, and under-utilized by, our profession (Berkley, 2001; Orman, 2002; Randles & Smith, 2012; Strand, 2006).

Moreover, the exclusion of composition as an accepted area of applied study within music teacher preparation programs may impinge on the identity formation of young composers as they put on a transient identity, that of performer, to gain access to education. Nelson writes, “a person’s identity is damaged when she endorses, as part of her self-concept, a dominant group’s dismissive or exploitative understanding of her group, and loses or fails to acquire a sense of herself as worthy of full moral respect” (2001, p. xii). In the case of the young composer who wants to be a music teacher, the admission fee at the gate of collegiate study is the forfeiture of the composer-self. How many would-be music teachers are composers until they are told at the point of auditioning for music school to identify their instrument or voice part? Why does the composer’s journey to become music teacher begin with a requisite loss of musical identity and self-integrity?

Music teacher identity, at core, involves an affective stance dependent upon power and self-agency (Zembylas, 2003). When some musical identities are positioned as not worthy of attention and musical passions are negated, future teachers and music education as a field are limited to a closed-loop conception of music, music-making, and music teaching. Writing in opposition to this type of practice, Reimer states:

All human beings require an education of sufficient depth and breadth to enable each to become as genuine, as distinctive, and as personally developed as possible. That necessary dimension of human becoming is smothered, often to extinction, by approaches to education stressing identicality rather than individuality (2014, p. 31).

The identicality the Reimer decries is not a natural order mandate; rather, it is one created by music teacher education. As such, music teacher education has the power to consider new options. What might composers bring to the field of music education? What insights do they possess that may differ from the viewpoints of performers? How might the presence of composers—with their unique ways of thinking about music, making music, and teaching music—expand conceptions of what music education might become and how music teaching and learning could evolve? These questions must be considered if music education’s offerings and practices are to become truly inclusive.

Considering the Composer-Educator. Music teachers who pursue composition as their primary area of expertise can offer unique insights to the practice of music education. While pedagogies of composition and performance share concern for historical foundations, technical skills, and the acquisition of domain-specific vocabularies, they do differ in significant ways. Teachers of performance select repertoire, engage in score study, and consider the composer’s intention in partnership with their own artistic interpretations as they guide students in preparing performances. The final product is one that the teacher can envision before instruction even begins.

Teachers of composition are faced with different challenges. The music that the teacher and students will study does not exist at the outset of instruction. The teacher does not have to develop a sense of the composer’s intention from the score, because the composer is right there, beside the teacher, present as the authority on their own work. As the score is in a state of evolution for much of the process, the performance cannot be envisioned with any accuracy until it is eminent. These conditions change the act of music teaching and learning.

In practical terms, composers have a personal investment in the creation and performance of their music. As such, they may be more likely to construct a curriculum that places the generation of new music in balance with music-making activities sustaining historical traditions and practices (Elliott, 1995). They may also significantly alter their students’ experiences of music through the inclusion of teacher-composed works (Lindroth, 2012; Randles, 2009). Moreover, as composers are educated to exercise generative creativity, they learn an open form of teaching where imagination and need drive learning. From the perspective of the composer, musical tradition is a point of departure—a visitor in the room, but not the master of what will be. By necessity, teaching is tailored to the learner because the learner controls nearly every aspect of the outcome. In such contexts, power structures between teacher and student are equalized and the educator’s expertise is a tool to be used by the student rather than the driving force of instruction (Allsup, 2013).

The differences between performance-focused and composition-focused teaching and learning suggest that there are multiple pathways for engaging students in music education. Each is unique and its presence adds value to the experience of the learner. It is also true that each form of teaching and learning offers insights only made evident through comparison with the other. As such, it is imperative that music teacher-educators embrace the possibilities found in welcoming composer as a music teacher identity.

Curriculum Considerations. Students focusing their applied study in composition can be as equally prepared to lead music programs with ensembles as are their playing or singing focused peers. Just as a trumpet player takes a Woodwinds Techniques course to learn how to play and teach woodwind instruments, so too can a composer take an instrumental techniques course to learn how to teach those instruments to students. The same holds true for all other manner of music education coursework and, when considered in reverse, further highlights the inequity created when vocalists and instrumentalists do not have the opportunity to learn to compose and how to teach students to do the same.

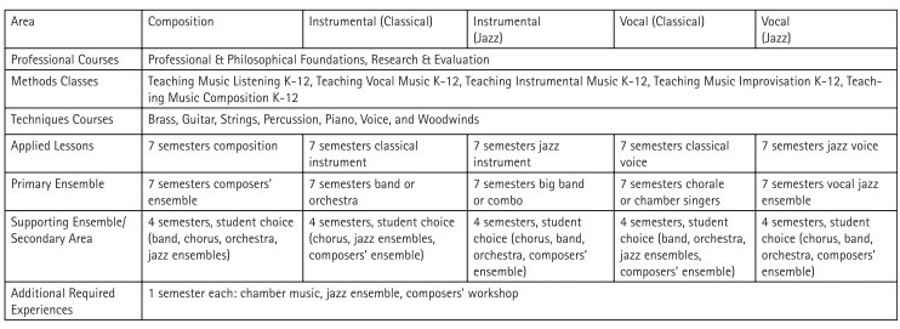

Most music education students training in the United States undertake the study of history, theory, aural skills, and conducting, along with other recommended courses adhering to the accreditation guidelines set forth music and teacher accrediting bodies. One approach to preparing music teachers within these frameworks would be to create parallel opportunities for composers to enroll in lessons and ensembles as shown in Figure 43.3.

Figure 43.3. Music education–specific coursework with possible applied area and ensemble requirement adaptations

This single model is but one approach and is well-suited to institutions that address K-12 music. The model could be adapted in any number of ways for schools organizing teacher training programs by sub-specializations in band, choral, general music, jazz, or orchestra.

Date added: 2025-04-23; views: 234;