Southern Ocean Biodiversity and Endemic Species

There is no greater contrast in diversity and abundance in adjacent habitats on Earth than between the continent of Antarctica and the surrounding Southern Ocean. Limited by the harsh, variable climate of Antarctica’s cold desert environment, terrestrial fauna there is among the least diverse in the world. Terrestrial vertebrates that do live on the Antarctic continent, such as seals, flighted birds, and penguins, are only temporary summer residents, with one exception. The single year-round endemic vertebrate is the emperor penguin, which famously breeds and nests over winter on the mainland thanks to the high density of its feathers and a thick blubber layer. In contrast, the Southern Ocean teems with abundant and diverse life.

The key difference is stability: although most of the Southern Ocean is quite cold (-2°C under sea ice to 4°C), it is relatively stable in terms of temperature and salinity. In contrast, the continent is subject to frequent storms, and its temperature can drop below -80°C during winter months. Many ectothermic organisms in the Southern Ocean, including many fish and invertebrates, have adapted to cold, stable temperatures and are able to live there year-round. In contrast, most endothermic species migrate north for the winter and return during the bountiful austral spring in October and November. Organisms grow and move quite slowly, and some fish such as the Antarctic cod and the mackerel icefish have actually evolved antifreeze proteins to prevent crystallization of their blood in the, potentially, -2°C water.

The Southern Ocean is very diverse, and new species are routinely discovered and described. In fact, in a single 30-min scuba or remotely operated vehicle (ROV) dive under sea ice, it is possible to document representatives of more than 50 percent of all known animal phyla. Many dives yield species unknown to science. More than half of all known marine species in the Southern Ocean have been described just in the past fifty years, even though the region has been sampled sporadically since James Cook’s time and consistently since 1900. This is due to continued advances in ice-capable research vessels, marine sampling methods, genetic sequencing, and ROVs. As of 2010, the Register of Antarctic Marine Species—a repository for all known Southern Ocean species data—has cataloged more than 8,800 species from more than 1,300 biological families, and that number continues to rise.

Despite the increasing numbers of taxa represented, marine sampling completed to date varies considerably with geographic location: most collections are completed near research stations due to the high costs in terms of time and money to reach more remote destinations. Different nations devote much of their research near their own bases—with Australia, New Zealand, and Asian countries in East Antarctica and South America and Europe focusing on West Antarctica. Russia and the United States have bases in both regions. The Amundsen Sea, Western Weddell Sea, and Eastern Ross Sea are historically underrepresented as they are remote from all stations and quite hostile to marine research due to the natural hazards of sea ice, icebergs, and storms. Additionally, Antarctic deep- sea samples are quite limited, as the logistics of deep benthic sampling are quite difficult, resulting in an overrepresentation of species found shallower than 500 metres, which is only a fraction of the deep Southern Ocean sea floor.

No Penguins in the Arctic Circle. One of the most popular wildlife features of the Antarctic is the penguin, a flightless aquatic bird most famous for its tuxedo-like markings. There are approximately seventeen different species of penguin, and they can be found on every continent in the Southern Hemisphere. Although popular culture has long associated the penguin with the North Pole, they are found no farther north than the equatorial Galapagos Islands (the Galapagos penguin). However, after the great auk—a bird that looked remarkably like a penguin but had no relation—was hunted into extinction in the early twentieth century, several attempts were made to introduce penguins into the Arctic Circle. Each of these attempts eventually failed for many reasons, including the rumored death of an introduced penguin at the hands of a woman in Norway who purportedly thought the creature was a demon. Laura G. Buschmann.

An open question remains as to which taxa may be underrepresented due to the greater difficulties encountered while working in certain parts of the Southern Ocean. Charismatic megafauna (e.g., penguins, seals, and whales) are well represented and may be entirely accounted for, but far less comprehensive is our knowledge of fish and benthic invertebrates. Of all benthic species, the best represented include mollusks (e.g., clams, snails, squid) and echinoderms (e.g., sea stars, sea urchins, sea cucumbers). Arthropods are less well described, with the exception of planktonic arthropods such as krill and shrimp. Still less is known about hemichordates, nematodes, tardigrades, and porifera (sponges).

Emperor penguin with chicks in the Antarctic (Shutterstock)

Because of its remote and isolated nature, the Southern Ocean is home to a large percentage of endemic marine species, especially in invertebrate classes. General endemism rates appear to be around 50 percent of known taxa, with some classes such as gastropods showing rates as high as 80 percent. These numbers may continue to rise as cryptic species are continually discovered through taxonomic expertise and genetic sequencing projects. This has important implications in terms of biodiversity and conservation, as many of the organisms found in the Southern Ocean are seen nowhere else. Because we still know relatively less about the biological communities in the Southern Ocean than elsewhere, it is difficult to ascertain the extent to which human impact has already affected the region. However, increasing temperatures and decreasing pH due to climate change are likely to have large effects on the Southern Ocean ecosystem.

Despite its cold, harsh conditions, the Southern Ocean is among the most productive marine environments on the planet. This is due to the seasonal cycle of sea ice formation and thaw, which drives upwelling. Upwelling occurs because the salinity of the seawater increases near sea ice and pools in brine pockets in the sea ice. When spring thaw melts the ice, this salinity change causes cold, dense water to sink, cycling relatively warmer deep water to the surface. Upwelling brings macronutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus and micronutrients such as iron toward the surface where they can be utilized by phytoplankton (e.g., microalgae, diatoms, dinoflagellates, radiolarians) in the process of photosynthesis in the austral spring in the euphotic zone.

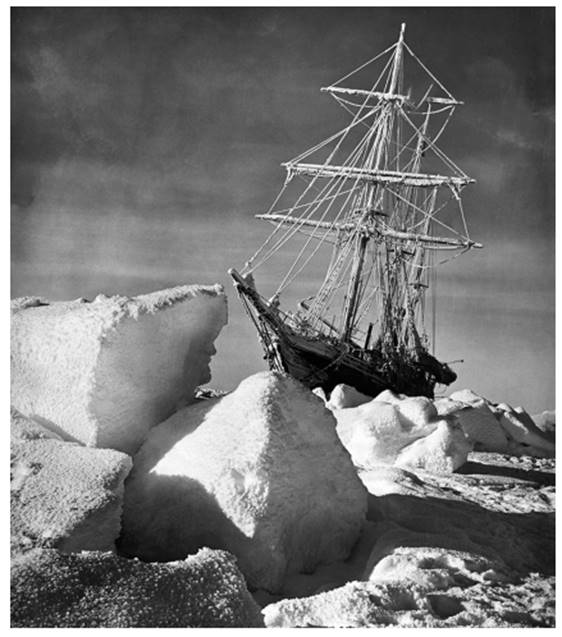

Ernest Shackleton’s ship, The Endurance, trapped in ice during the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914-17. Pack ice would ultimately crush the ship in 1915 (Frank Hurley/Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge/Getty Images)

Phytoplankton populations peak in early summer, and although microorganisms are tiny individually, the combined biomass of the phytoplankton accounts for roughly half of all global photosynthetic activity on Earth. We know this primarily from satellite imagery using a system called Sea-viewing Wide Field-of-view Sensors, which detects and tracks phytoplankton blooms. These blooms lead to zooplankton blooms, including the most prevalent species: krill. The Southern Ocean pelagic food web is less complicated than in most areas. Most food chains are quite short, representing relatively few trophic steps— many only three levels (e.g., phytoplankton ^ krill ^ whales).

During the height of the summer season, there are an estimated 500 million tons of krill in the Southern Ocean; this leads to the phrase “three degrees of krill,” meaning in most cases you are krill, you consume krill, or your prey consumes krill. Krill can reach densities of 10,000 per m3 in some blooms. There is intense competition in the summer season to gorge on krill. Whales, seals, cod, squid, petrels, albatross, and penguins all depend on krill or the predators of krill for their own survival, and many species migrate and breed during the summer months around this feeding season. Humans are also now a major predator of krill, taking an estimated 100 million tons a year for use as bait, animal feed, nutrient supplements, and food. Krill do survive in the winter as well, feeding on algae that grow on the underside of translucent sea pack ice.

Date added: 2025-08-31; views: 266;