Sea Peoples: Late Bronze Age Maritime Raiders Who Toppled Empires

The term “the Sea Peoples” is used to describe a confederation of seafaring marauders, invaders, and pirates who were active in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea between approximately mid-1200 and mid-1100 BCE. The precise ethnic identity and origins of these people are largely unknown and continue to be the subject of historical and archaeological debate. They had no known political structure or identifiable leaders, and their maritime activities appear to have been sporadic. Scholars generally assume them to be composed of groups with varying identities, with suggestions including the Etruscans, the Sardinians, the Mycenaeans, the Achaeans, and others.

The term “Sea Peoples” itself did not come into usage until the nineteenth century CE and is drawn from an Egyptian source, which described them only as the “foreign peoples of the sea.” Apart from this description and a few other Egyptian sources, no primary- source writings exist to ascertain their exact identity. Nearly all of what is known about them is taken from the Egyptian sources, a few archaeological finds, and assumptions rooted in larger historical circumstances, such as the collapse of the Late Bronze Age.

Prior to the appearance of the Sea Peoples in the Egyptian records, the Eastern Mediterranean region was dominated by the New Kingdom of Egypt and the Hittite Empire of Anatolia, present-day Turkey. Functioning as two “great powers” during the era referred to as the Bronze Age, Egyptian and Hittite stability afforded a long period of peace and commerce in the Mediterranean. However, for various reasons, 1200 BCE marks for historians the beginning of the Late Bronze Age and the beginning of the collapse of several stable powers in western Asia, including the Egyptians and the Hittites among them. The start of this period also coincides with the era in which the Sea Peoples were active in the region.

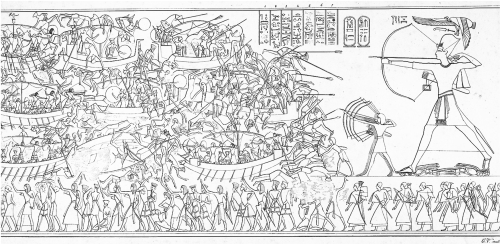

Illustration of battle with the Sea People, Medinet Habu, Egypt, c. 1832-44. This famous scene from the north wall of the Mortuary Temple of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu is often used to illustrate the Egyptian campaign against the Sea Peoples in what has come to be known as the Battle of the Delta (New York Public Library).

As such, it is unclear from the evidence whether the activities of the Sea Peoples were a primary cause of the collapse of the Egyptians and Hittites or whether they took advantage of the ensuing chaos to make their presence felt. Nonetheless, at least three Egyptian pharaohs fended off attacks from the Sea Peoples on several occasions during the New Kingdom of the Late Bronze Age. Egyptian accounts of these battles provide the first and primary observations of the Sea Peoples. In the second year of his reign, the pharaoh Ramses II (1279-1213 BCE) recorded a naval victory over the Sea Peoples, some of whom were incorporated into his army as auxiliaries after their defeat. Three years later, in 1274, Ramses tried to retake an important coastal trade center earlier lost to the Hittites called Qadesh. Although the outcome of the battle is ambiguous and arguable, the Egyptian records claim the Sea Peoples were acting as allies of the Hittites, although some also served among Ramses’s forces; that is, the same term used to refer to them at Qadesh, the Shardana, was also used by Ramses during the earlier naval engagement. According to some scholars, the term “Shardana” refers to the Sardinians, but this remains speculative.

Ramses’s son, Merneptah (1224-1204 BCE), also defeated a group of Sea Peoples at the Battle of Piyer in 1218, which included the Shardana again. As was the custom for Egypt, many of them were made captive, and the victory was immortalized on the Merneptah Stele at Thebes. Following this, the Sea Peoples reappeared around 1200 in Anatolia during the reign of the Hittite Emperor Suppiluliumas II (c. 1220-1200 BCE), where they, along with other groups, precipitated the fall of the Hittite Empire after ravaging the coastline and destroying the city of Tyre. After this, by some accounts, one group of Sea Peoples, the Peleset, settled in present-day Palestine, where they intermixed with other Semitic peoples to form the group known in the Bible as the Philistines (taken from the Peleset), but this remains mostly conjectural.

Some credence is given to this theory because, in 1182, during the reign of Ramses III (1190-1158 BCE), a coalition of Sea Peoples, including the Shardana, the Peleset, and others, according to the records, attacked Egypt from the north, on the border with Palestine, and by sea along the Nile Delta. Following his defense against the sea borne invaders and a final land victory at the Battle of Xois, Ramses’s success was commemorated on the walls of his mortuary at Medinet Habu, where some of the invaders are depicted with horned helmets like the Shardana had been shown earlier. Others, specifically those who invaded overland, are shown with feathered headdresses in a style similar to the carved water-bird heads that frequently adorned the bows and sterns of the Sea People’s ships. Adding still to the mystery of their identity, some of the Sea Peoples at Medinet Habu are shown with swords, spears, and round shields and wearing short kilts, suggesting to some scholars Mycenaean or even Minoan origins. The uncertainty and mystery over who the Sea Peoples were will likely continue to be the subject of debate. More certain is that, despite their relative obscurity, the Sea Peoples represented disparate groups of mariners who sought advantages and opportunities from the decline of the greater powers in the region, that is, the Egyptians and Hittites. The degree to which they either generated the decline or merely took advantage of it is almost impossible to conclude. They nevertheless left an impact on history.

FURTHER READING: Cline, Eric. 2012. The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Oren, Eliezer. 2000. The Sea Peoples and their World: A Reassessment. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 3;