Forests, Tropical. Characteristics of Tropical Forests

With boreal (northern) and temperate forests, tropical forests are one of the three major forest types in the world. But tropical forests are by no means uniform. The upper latitudes of the tropics, which are arid or semiarid, are covered by savanna woodland, in which trees are widely spread over grassy plains. Tropical forests are particularly prevalent in Africa, Australia, northwest India, and northeastern Brazil.

They are the result of low and erratic rainfall but also probably of centuries of rapacious cutting by humans. It is not until zones of high temperatures and high humidity are reached on either side of the equator that "tropical" forests appear, variously described as "dense," "lush," "luxuriant," "prolific," "multispecied," "impenetrable jungles" dominated by hardwoods, heavy with insect and wildlife, and consequently rich in biodiversity (biological diversity as indicated by numbers of species of animals and plants).

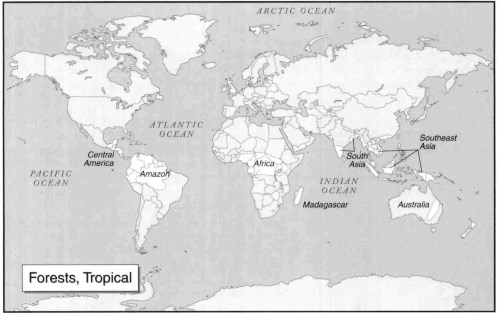

Yet, even these forests are of two kinds: the evergreen broad-leaved forests that constitute the cores of Amazonia, Zaire, and southeast Asia (often called "equatorial forests") and the surrounding tropical, moist, deciduous forests (also called "monsoon forests") that lose their leaves in the dry season.

The exact mapping—and hence known area—of forests is still largely guesswork because most comprehensive surveys are based on satellite images that distinguish mainly closed forest (i.e., a minimum of 20 percent forest crown cover of the land surface, which could be tropical, boreal, or temperate) and open or woodland areas.

Nonetheless, a reasonable estimate would be that closed forests cover about 2.8 billion hectares, or 21 percent of the Earth's land surface, and woodlands about 1.7 billion hectares. Of the closed forest, just over 1.2 billion hectares are tropical forests, the overwhelming bulk (90 percent) being tropical moist forests. Of these, about half are in the Amazon River basin, with the other half shared about equally by Africa and southeast Asia.

Characteristics of Tropical Forests. Tropical forests are qualitatively different from other forests, particularly temperate forests, to which they are sometimes compared. Temperate forests have been altered by millennia of clearing and manipulation to create productive farming lands, without any apparent detrimental effect. In fact, their clearing has seemed to be the first step to economic development and advancement and a model of how to develop the tropical forests.

However, the tropical forest is different. First, its variety and density of life and species are astounding, and elimination of the forest leads to unknown loss. Estimates vary widely, but it is thought that tropical forests contain between 5 and 30 million animal species—ranging from vertebrates to insects—and an untold variety of plant life. It may be more because many plants have still not been identified, and the tropics may contain more than 90 percent of all known species.

Moreover, this rich diversity is the theater for much ingenious adaptation and innovation that may be central to human understanding of the fundamental problems of evolution and ecology. At a more utilitarian level the genetic diversity has been likened to a "source-book of potential foods, drinks, medicines, contraceptives, abortificents, gums, resins, scents, colorants, specific pesticides, and so on, of which we have scarcely turned the pages" (Poore 1976, 138).

Secondly, for all their variety and robust vegetative exuberance, tropical forests and their soils are inherently infertile, deficient in soil nutrients, poor in structure, and if cleared are liable to severe erosion and leaching with the subsequent formation of a subsoil, hard iron-pan layer. Unlike in temperate areas, only small patches of forest are suitable for agriculture.

Rain in the tropics does not fall as a gentle drizzle but rather as short, sharp downpours that leach and erode the exposed soil when the forest and its binding roots are removed. After the soil is denuded, the rapid runoff of rainwater not absorbed in the soil has a knock-on effect downstream in areas well outside tire forests in the form of unregulated and erratic water supply and excessive sedimentation that clogs reservoirs.

Although it is a scientifically contentious issue, there is some evidence that large expanses of forest have local and even global effects on rainfall and climate. Certainly their clearing and burning put enormous amounts of carbon into the atmosphere.

Finally, tropical forest are not uninhabited. They are home to many millions of tribes people who have adapted to this habitat by hunting, collecting, and practicing swidden (rotational, slash-and-burn) agriculture. Again, only estimates can be made, varying from 50 to 250 million people. In addition, the bounty of the forest in providing game, fodder, fuel, and forage is essential to the livelihood of farming communities on its edges.

Date added: 2023-09-10; views: 775;