AIDS: Overview. HIV

AIDS is the most devastating new infectious disease that has originated in the recent past. First identified as a new clinical entity in 1981, it has already killed more than 25 million people. It is estimated that another 40 million are already infected with the causative agent, the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). AIDS was initially recognized when certain unusual diseases, such as Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, Mycobacterium avian tuberculosis, and Kaposi sarcoma were seen in groups of young homosexual men who knew each other.

A common underlying abnormality was a severe loss of T helper cells, or CD4 cells, which are considered the major driver of the immune system. Within a few years the same syndrome was seen in injection drug users, hemophiliacs, some blood transfusion recipients, some Haitian and African immigrants who moved to the United States or Europe, and a few infants.

Initial attempts to identify the cause of AIDS focused on such factors as rectal exposure to semen, and amyl or butyl nitrate ‘poppers,’ which were often used by homosexual men to enhance sexual performance. Infectious agents were subsequently considered, especially those known to be transmitted sexually, such as herpes, and hepatitis B virus, which was already known to occur at elevated rates in heterosexual men. Human retroviruses were not well known or appreciated at the time AIDS was first recognized.

The first human retrovirus had only been identified a year or two earlier, in association with a rare form of cutaneous leukemia. However, for the few virologists familiar with the first human retrovirus, a related virus seemed logical to consider as a cause of AIDS. Among the reasons to look for a retroviral cause was the knowledge that retroviruses were known to cause immunosuppression in animals such as cats, and that the first human retrovirus (human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I, or HTLV-I) infected the same T helper lymphocytes that were depleted in AIDS patients.

Within a few years it became clear that the human immunodeficiency virus was the cause of AIDS, that the virus and the disease (HIV/AIDS) had spread around the world, and that the highest rates were in Africa. It also became evident that the disease usually took 3-10 years to develop following infection with HIV, and that the disease was almost always lethal. Antiretroviral drugs, especially those that could be used in combination chemotherapy, were not available until the mid-1990s. By this time, highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) could be used to save the lives of AIDS patients.

HIV. HIV was identified in AIDS patients using serological techniques, analysis for reverse transcriptase activity, and electron microscopy. HIVs are lentiretroviruses, a genus subset that are more complex than the oncoretroviruses earlier linked with leukemias in chickens, mice, and cats. All retroviruses replicate using reverse transcriptase, an enzyme that is carried in the virus particle. This allows the viral RNA genome to be transcribed into DNA, a function that the cell cannot do alone. The DNA copy is then integrated into the cell chromosomes of the lymphocytes or monocytes that the virus infects.

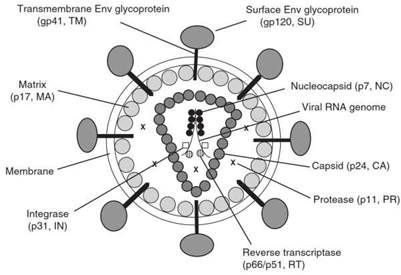

The virus particles have projections on their surface, designated the gp120 because they are glycoprotein molecules of 120 000 d. They specifically attach to the CD4 receptor on lymphocytes and monocytes. This reaction between the gp120 opens the molecule so that it then attaches to a second cell surface receptor, or a coreceptor.

Several coreceptors are utilized, but either CCR5 or CXCR4 is usually used. This allows the virus to pass through the cell membrane and uncoat the RNA genome to be copied by the accompanying reverse transcriptase. The DNA copy becomes double-stranded before being integrated into cell DNA as a complete viral genome, containing all nine genes and various regulator sequences.

Both the viral progeny RNA genomes and the mRNAs for the viral proteins are then transcribed from this integrated ‘proviral’ DNA in much the same way that cell proteins are made. However, virus production normally occurs only when cells are stimulated, or undergo cell division, allowing the virus to hide in latent form in many cells.

This in turn makes it impossible to get rid of the virus from the entire body once the infection is established, as only viral proteins or viral particles can be targeted by drugs or immune responses. The assembly of progeny virus particles also occurs at the cell surface, and after activated cells produce a large batch of progeny virus, they die. As a result, the volume of virus released into the blood increases as more cells are infected, and a lowering of CD4 cell numbers is directly correlated with an increased viral load (VL) in the blood.

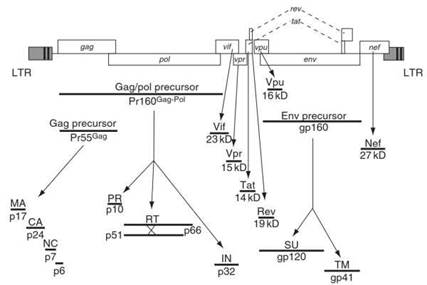

The viral particles are about 100 nm in diameter and have a triangular core that is electron-dense when visualized in electron micrographs (see Figure 1). The viral genome has about 10 000 nucleotides, with a long terminal repeat sequence for activation and regulation at each end of the genome. The three largest genes are gag, pol, and env. gag encodes for a polyprotein that is cleaved to make four smaller proteins, which compose the structure of the virus core (see Figure 2).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of a mature HIV-1 virion. Reproduced from Knipe DM and Howley PM (2001) Fields Virology, 4th edn., p. 2002. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, with permission of Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Figure 2. HIV genome with encoded proteins. Reproduced from Knipe DM and Howley PM (2001) Fields Virology, 4th edn., p. 1976. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, with permission of Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

The pol gene encodes three essential enzymes: the protease, the reverse transcriptase, and the integrase. All three of these enzymes represent key targets for antiretroviral drugs. Almost all of the major drug combinations (HAART) that are initially used to treat AIDS are composed of two different classes of reverse transcriptase inhibitors and, at least in developed countries, where cost is less of a concern, one protease inhibitor.

The env gene encodes gp120, which is initially made as a gp160. The gp160 then undergoes cleavage to make gp120 for the surface spikes, and gp41, which becomes the transmembrane layer that holds the embedded spikes. Three genes, tat, rev, and nef, make proteins that differentially regulate the production of viral components in major ways during the replication process. Three additional genes, vpr, vpu, and vif, often called ‘accessory genes,’ perform lesser regulatory functions.

HIV undergoes an extremely high rate of genomic variation or evolution. This is often described as accumulative sequence (nucleotide or amino acid) changes that can equal 1% per year in a single infected individual. The high rate of genomic changes occurs because the reverse transcriptase allows a high rate of mutation errors, and because HIVs have a diploid genome, which facilitates recombination when a single cell becomes infected with two different parental HIVs. When this high rate of viral mutation occurs in the selection environment of an infected person, resistant variants may emerge and rapidly become the dominant viral population.

In the case of AIDS patients on drugs, this means selection pressure to make drug-resistant viruses. In the case of virtually all infections, immune responses result in the further selection of viruses that resist each particular immune response. The infected person rapidly makes antibodies to gp120, which can neutralize a particular phenotype. Immunoselection then allows another phenotype to emerge and dominate the infection. This is followed by rapidly repeated cycles of new neutralizing antibody responses followed by cycles of viral selection to negate the effects of the neutralizing antibodies. The same type of immune selection pressure occurs with cell-mediated responses, which may occur to epitopes in most of the viral proteins.

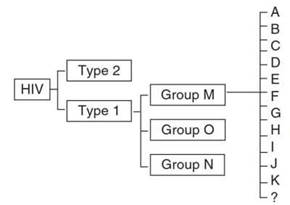

HIV type 2 (HIV-2) is a related virus that is primarily found in West Africa. It is about 40% related to HIV-1 at the nucleotide sequence level, and shares antibody cross-reactivity for several proteins. Although HIV-2 can also cause AIDS that is clinically indistinguishable from HIV-1 AIDS, it is less virulent and less transmissible. While about 95% of adults infected with HIV-1 show clinical signs and symptoms of lethal AIDS within 10 years after infection, only about 10-20% of HIV-2-infected people show evidence of AIDS within the same time frame.

Different HIV-1 viruses predominate in different parts of the world, although most are present in sub-Saharan Africa. These viruses are divided into subtypes according to phylogenetic nucleotide relatedness. Four subtypes, designated A, B, C, and D, each account for at least several million infections in people (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. HIV types, groups, and subtypes

Two circulating recombinant forms (CRFs), which are hybrids of two subtypes, also account for infections in at least a few million people. These are designated CRT 01 A/E, which was earlier called subtype HIV-1 A/E or E, and CRF 01 A/G. Two other groups of HIV-1 viruses, M and N, have been found in small numbers of people, and at least five other subtypes and 12 other circulating recombinant forms have been described.

All available evidence indicates that the HIVs moved into human species quite recently from subhuman primates. The earliest evidence for HIV-1 in people is from about 50 years ago. Viruses closely related to HIV-1, particularly the M and N groups, have been identified in chimpanzees in the region of Gabon and Cameroon. Viruses almost indistinguishable from HIV-2s have been identified in mangabey monkeys in West Africa. A variety of species of African monkeys have infections with viruses that are closely related to HIVs, called the simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIVs).

For some species, such as vervets, the majority of adult animals caught in the wild are infected. African monkeys and chimpanzees do not appear to become ill with infections, suggesting that they have successfully evolved with the viruses over a long period of time. Asian monkeys do not appear to be infected under natural conditions, and when captive rhesuses are infected they develop AIDS.

Date added: 2024-03-11; views: 539;