Treatment. Denialism. Prevention

Treatment. The first drug available for treatment of clinical AIDS, zidovudine (ZDV or AZT), became available in the late 1980s. As additional drugs became available in the early and mid-1990s, it became apparent that most patients could achieve long-term remission and dramatic clinical improvement if they strictly adhered to a schedule of taking three or more drugs together.

Selection of the drugs is based on choosing combinations that are least likely to have cross-reactive patterns of drug resistance. Designated ‘HAART,’ for highly active antiretroviral therapy, this approach became highly successful as more drugs became available. The combinations that are used most frequently in the developing world, where cost is a serious problem, usually include two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (such as ZDV and lamivudine, or 3TC) and one non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (such as nevirapine).

Although all three drugs are reverse transcriptase inhibitors, they do not cause mutations that cause resistance to more than one drug at a time. However, some drugs, such as nevirapine and efavirenz, would never be used together, as they share the same drug resistance mutations.

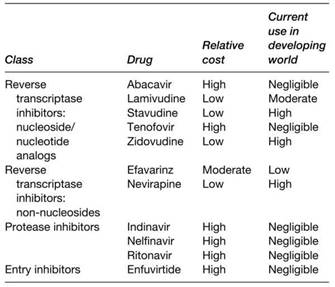

Most of the drugs that are commonly used are listed in Table 3. Most HAART regimens used in Western countries, where cost is less of a problem, would include a drug from the protease inhibitor category. As patients develop drug resistance to the more common drugs, they are switched to new regimens that are still efficacious. Drug resistance occurs much more rapidly when patients do not adhere to scheduling doses, or when only one or two drugs are taken rather than three or four.

Table 3. Representative antiretroviral drugs used for treatment of HIV/AIDS

More drugs are now available in slow-release forms, which may decrease the frequency that they must be taken from two or three times per day to once per day. However, a major problem with adherence to rigorous schedules for taking the drugs has always been the accompanying toxicity, or side effects. Some of the most common are gastrointestinal disturbances and peripheral neuropathies. The discomfort associated with these side effects is a major reason why certain patients may not adhere to the required schedules for taking the drugs.

In developing countries, the same or closely related drugs are often used as chemoprophylaxis, taking only one or two at once, to prevent transmission of HIV from infected mothers to their infants. Because all viral genomes, including those with drug resistance mutations, are archived as provirus in the host cell DNA, it may be difficult or impossible to rid the body of drug-resistant mutants once they are present at high levels.

All drugs used to treat AIDS are targeted to HIV replication. However, as many of the opportunistic infections, such as tuberculosis or fungal infections, become established in the immunosuppressed individual, it is also essential that drugs be used to target the opportunistic organisms. It may also be efficient to give drugs such as cotrimoxazol as prophylaxis to prevent the outgrowth of such opportunists in individuals who have already lost most of their CD4 cells but have not yet developed clinical AIDS.

Denialism. As a new epidemic of global proportions, AIDS was very unusual. As an infectious disease, AIDS was unprecedented in that almost everyone developed a lethal illness, but only after an induction period of several years. Infectious agents normally cause disease after just a few days or weeks, and most only cause disease in some of those that become infected. Although some infectious agents, such as papilloma viruses, cause diseases such as cervix cancer after many years, such outcomes are unusual. With HIV, the outcome of lethal immunosuppression is almost universal.

Because the clinical outcomes that are observed include a wide range of things, such as tuberculosis and some cancers that also occur in the absence of HIV, a small group of scientists or ‘denialists’ refused to accept the evidence that AIDS itself was a disease and/or that HIV was the cause. Yet, if the disease is defined by immunosuppression caused by destruction of T cells, as it should be, the epidemiologic evidence is overwhelming.

Similarly, the compelling evidence that AIDS pathology can be reversed by drugs that target HIV is itself strong evidence that the virus causes the disease. Despite this, some denialists tried to twist this evidence by suggesting that ZDV was a cause of AIDS.

In the earlier stages of the epidemic, particularly the late 1980s and early 1990s, the denialists found some sympathizers among AIDS patients in Western countries. As with some other lethal diseases, desperate patients may be particularly susceptible to arguments that dispute the existence of their lethal condition.

However, when public health officials condone such denialist positions, as was the case in the Republic of South Africa, the lives of many individuals may be lost. If people are encouraged to believe that AIDS is not a sexually transmitted infectious disease, they have no reason to avoid exposure to HIV. If they believe that antiretroviral drugs are not an effective way to inhibit HIV, they do not use drugs for chemoprophylaxis or treatment.

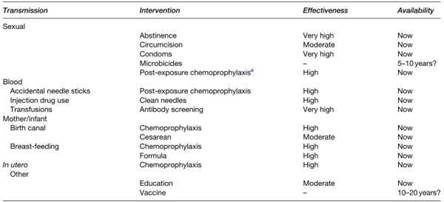

Prevention. Risk for HIV infection by sexual means can be reduced in various ways. Abstinence from sexual intercourse and/or reducing the number of partners and using condoms are perhaps the most obvious (see Table 4). Ways to reduce the efficiency of transmission among adults coinfected with herpes are also being investigated, such as treatment of the herpes with acyclovir.

Table 4. Interventions to reduce or prevent HIV infection

Avoidance of rectal sex may also be important, particularly for homosexual men. Programs to learn one’s status through voluntary testing and counseling are valuable, particularly when accompanied by behavior change. In recent studies, male circumcision appears to reduce risk of infection by 40-60%.

A major problem in developing countries is that women often cannot learn the HIV status of male partners, yet they wish to engage in sex to have children. The development of vaginal or oral microbicides, which can be controlled by the woman, has been proposed to address this problem. Unfortunately, the first generation of experimental microbicides were broad-spectrum toxic compounds that also caused damage to the reproductive tract epithelium, and had either no net beneficial effect or increased risk. The current generation of microbicides being tested in trials includes specific antiretroviral drugs.

Although they could also cause the development of drug resistance if used accidentally in patients that are already infected, such preparations would not be spermicidal and also seem more promising to reduce risk of infection. Antiretroviral drugs have been proven to be very effective when used as chemoprophylaxis following accidental medical exposure, such as by needle sticks with HIV- infected blood. Various antiretroviral drugs have also been shown to be highly effective to reduce mother-to- infant transmission of HIV.

In this situation, drugs may be given to the mother during pregnancy and at the time of labor, as well as to the newborn infant. Drugs may also be given to the mother and/or infant while breast-feeding to reduce transmission by this route. Even the use of a single drug, nevirapine, during labor can prevent birth transmissions by up to 50%. However, this approach is less effective than giving multiple drugs for longer periods, and it also gives high rates of nevirapine resistance in mothers given such treatment.

Most transmissions associated with blood transfusions have been prevented by screening donors for HIV antibodies. The addition of blood screening techniques to pick up the few who may be in the pre-antibody window using PCR or antigen techniques are effective, but expensive. For injection drug users, the availability of clean needles will greatly reduce transmissions. Unfortunately, needle exchange programs have been blocked by some officials who believe they may contribute to the use of illicit drugs.

An effective vaccine against HIV has long been sought as an ideal way to prevent HIV infections. Unfortunately, more than 15 years of vaccine research have not yet resulted in any promising leads. The biggest impediment appears to be an inability to induce sufficient crossreactive immunity to cover the wide range of variants that evolve during natural infection.

However, newly innovative approaches to identify more appropriate antigens and better immune responses are underway. Although previous approaches have been disappointing, vaccine research still has many promising avenues for future experimentation.

Further Reading:

1. DeVita VT Jr, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, Curran J, Essex M, and Fauci AS (eds.) (1997) AIDS: Etiology, Diagnosis, Treatment and Prevention, 4th edn. Philadelphia, PA: J.B. Lippincott.

2. Essex M (1999) Human immunodeficiency viruses in the developing world. Advances in Virus Research 53: 71-88.

3. Essex M, MboupS, Kanki PJ, Marlink R, andTlou S (eds.) (2002) AIDS in Africa, 2nd edn. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

4. Johnston MI and Fauci AS (2007) An HIV vaccine: Evolving concepts. New England Journal of Medicine 356: 2073-2081.

5. Kahn JO and Walker BD (1998) Acute human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. New England Journal of Medicine 339: 33-39.

Date added: 2024-03-11; views: 482;