Funeral rites in ancient Greece

The end of life has been accompanied by major sentiment for many societies. Examining the individual’s burial and the concept of the afterlife helps explain society at that time and an individual’s place in society. Just as crucial were the funeral rites for the deceased, as they provided a bridge between the living and the afterlife and led to the burial. Although most of the evidence of funerals comes from Athens, it is probable that most other Greek cities had similar views. Honoring the dead is a conservative practice with very little change, and Athenian ideology must have had a basis in the pre-Classical period.

It is known that the Athenians greatly prized being buried in Attica—hence the desire to bring home the remains of dead soldiers. If an individual could not be buried, it was viewed as a great penalty. The primary rites for the funeral rested with the immediate family, and in fact, it was improper if a family member did not perform them. Usually, the son had the primary duty to bury the father. Funerals were expensive, and most of the funds were spent not on tombs, but on the preparation for and execution of burial and funerary rites.

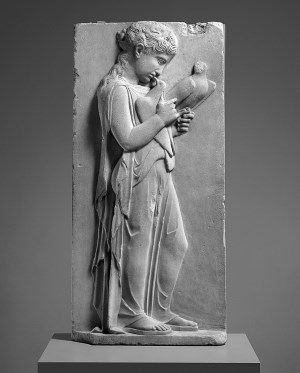

Grave stele of a child. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Fletcher Fund, 1927)

Funeral rites provided a way for family and friends to grieve the passing of their loved ones. These rites provided dignity to the individual and can be seen in the Homeric poem the Iliad. Ensuring that the dead were well treated allowed the deceased to pass over to the other world. The role of women in the funeral rites was paramount. In Sophocles’s Antigone, for instance, Antigone is persecuted for performing funeral rites for one of her brothers, who has been ordered to be left unburied because he had attacked the city of Thebes. The play argued that the laws of the gods, expressed in funeral and burial rites, were more important than the laws of men.

There were three parts to funeral rituals. The first was the laying out of the body, or the prothesis, followed by the funeral procession or ekphora, and finally the disposition of the body by either inhumation or cremation. These tasks were usually performed by women, usually the spouse or another close family member.

The prothesis began when the last breath, the sign of the living’s spirit or psyche, left the body. The first part was the ceremonial washing of the body. Female family members usually performed this task, and afterward they would anoint the body with oil. Usually only those women over sixty, or if none existed in the family, other close family female friends over sixty would perform the rite.

They would then dress the body in simple clothes (wrapped in a shroud, or endyma) and place it on a high bed (kline) in the house on a thick carpet (stroma), covered with an epiblemata. The head was elevated with proskephalaia (pillows), and the chin was kept shut with othonaie (straps) to prevent the mouth from being opened. The prosthesis would take place at the home and was done on the day following the death. The ritual was only one day long, and Plato indicated that it was to confirm that the individual was truly dead. It was at this point that relatives and friends would pay their last respect and mourn the passing.

Numerous pieces of pottery, especially on the lekythos or pottery for storing oil from the Geometric period, show several mourners lamenting the dead. Before the Peloponnesian War, the scenes usually show the multifaceted steps, which were often time consuming and expensive. Several people would be involved in this process. During the war, the time requirements and costs shifted the ceremony from an extensive prospect to a more subdued event, as seen in the lekythos created after the war, with fewer individuals present and funerals no longer being required for the dead to enter the afterlife. This may have been the reaction that Sophocles was attacking in Antigone. Having the prosthesis at home instead of in a public ceremony allowed grief to remain private.

The body was then transported to the grave site on the third day (ta trita) before sunrise, led by the men and followed by the women. The second part of the rite, the funeral procession, was normally confined to the side streets, and public display of grief and loud clamor was discouraged. It was to be a private event, not a public spectacle as in Rome.

The body was covered with only the head exposed as it was carried by pallbearers or on a cart. Women who took part in the procession were required by law to dress appropriately and were limited to certain ages. For example, women were not permitted to go to a tomb unless they were related to the dead or it was the actual day of internment. In addition, women could not visit a tomb at night unless they rode in a cart with a lamp.

When the procession arrived at the grave, the body was lowered into the pit without ceremony. Athenian law forbade the sacrifice of oxen, although there was probably a small sacrifice or ceremony over the grave to ensure that the dead was received and the land was purified so it could continue to be used by the community as passageways, sanctuaries, or even workshops. One such ceremony was the choai (drink) offering; often found at the grave and in the tombs were drinking vessels for this last libation for the departed.

The funeral party then returned to the home of the dead, which had a notification of the death containing a warning of the miasma (pollution) that resided in the house. When the mourners returned, they celebrated the perideipnon, or commemoration meal. This was not done at the grave, but rather in the house of the dead. It was probably a time for the family to commemorate the memory of the dead one last time and for others to offer sympathy to the family. A basin of water was placed outside so that mourners leaving the house could cleanse themselves of the miasma. Water was always important to the Greeks for purification and cleansing.

When people knew that they were going to die, they often did the ritual bathing themselves, as Socrates did to save women the trouble. In mythology, Alcestis, knowing she was about to die, bathed and put on her funeral dress. Oedipus likewise bathed and offered the ritual drink. The vessel of water placed on the outside of the house on the day of the funeral was not only for cleansing of the mourners, but also to purify the house. It also appears that at the grave site, mourners may have performed a ritual involving water in order to purify themselves.

On the ninth day after the burial, the celebration of the ta enata took place at the grave site. Family and friends gathered to perform this customary rite. Although nothing is known of the rites or celebrations, they were noted in the law courts, so that they were probably well established and required. There appears to have been a final ceremony, although when it was done is not clear. The ta nomizomena was where the family celebrated the return to normal life and no longer was in mourning.

After the immediate funerary rites, the family commemorated the dead annually. These celebrations appear to have been more important than the actual burial or the ninth-day celebration. These annual ceremonies were performed by the son, and some references make it clear that adopting a son was done to ensure the annual commemoration of the dead took place.

One such celebration was the Genesia, whose name comes from the word gene, meaning “family,” which Herodotus mentioned but did not describe. It must have been known to his readers, though, since he mentioned it in reference to an annual celebration of the dead. The Genesia is also mentioned by other writers as a festival. This celebration may have been the annual festival of commemorating the dead in Athens.

The family visited the tomb annually and left trinkets such as flowers to show their appreciation of the departed. At home, the family celebrated the “ancestral objects” handed down from generation to generation. They were obviously important, since one needed to show that they had these objects in order to hold public office, and they were to be kept safe so as not to bring disaster upon the family.

The funerary rites allowed the living to honor the dead, and they were seen as a way to keep the person’s memory alive. The rituals were highly prescribed, indicating that they changed little over time. This also allowed each generation to have a connection to the past through ceremonies that were common. Unlike the Romans, who had lavish funerals and public ceremonies, the Greeks viewed the funerary rites as a private matter that allowed families the opportunity to honor their departed simply and nonostentatiously.

Date added: 2024-09-09; views: 370;