Chemical Spills Versus Oil Spills. Booming and Containment

Chemical spills, unlike crude and other oil spills, are generally confined to one product. While one cannot write a single chemical equation for an “oil" or “petroleum product," one can write a formula for most solvent or chemical spills.

The selection of spill control materials for spill prevention and containment needs to be based upon the chemical formulation of the spilled material. If the selection of containment materials is not suited to the material spilled, the spilled materials can easily dissolve the containment barriers or have energetic chemical reactions with the barrier materials. Consideration of the type of materials and their potential quantities is important in developing an effective spill control program.

Booming and Containment. Many of the compounds in crude oil float, creating a layer on the surface of water which can be as little as a few microns (creating a sheen), to millimeters, to several centimeters - the height of the top of the boom (5-10 cm). One of the ways to prevent the oil from spreading is to provide a physical barrier or oil boom. The boom itself is a plastic or rubber material not attacked by the oil. The boom material may also contain a heavy cloth or plastic affixed to a flotation device, and it is weighted on the bottom so that it forms a vertical barrier to the spreading of an oil slick.

There are many types and kinds of oil booms. Some are weighted with chains for stability, and others have internal weights incorporated into the boom material. The weight keeps the boom upright, forming a containment barrier. The flotation booms sizes range between 0.2 and 1.22 m in depth. Some booms are designed to be towed, whereas others are designed to be stationary. The towed array booms are attached to top and bottom cables which hold the boom materials together both to assist in deployment and to provide anchorage or a method of towing. Some booms are metal and are fire resistant, used when burning off an oil slick is the preferable method of treatment.

The manufacturers of booming equipment have their own designs: the US Minerals Management Service, the USEPA, and USCG and the Canadian Government have developed a manual on the effectiveness and types of oil booms available. The evaluation is over 20 years old but is still relevant and a good information source.

The design of the boom and its freeboard (height above water), size, depth below water, wind, and wave action can have a significant effect on the performance of the containment booming. Wave heights of 0.7 m or more, often generated by a 7-15 mile per hour wind, can cause booms to be ineffective in containment of floating oil. In harbors, wave heights are lower than in the open sea and booming more effective. Booming is often placed around moored ships to contain oil spilled during refueling operations.

A spill control boom’s performance is affected by wind and wave action and the design of the boom: the height and depth of the boom on the water, and the position of the floatation attachment. For booms with lower freeboard, “wash over" can be a significant problem. In general, booming with greater dimensions (1.25M vs. 0.31M total height) are more effective because of the projections both above and below the water.

Some spill containment booms are designed for towed arrays - to be pulled behind a vessel to collect the oils. These booms are attached by a top and bottom cable linking each section of the boom to its neighbors: The boom is then deployed in a U configuration and pulled through the water much like a buoyant net or parachute. Towed arrays are often partially successful, especially in quiet open water but have challenges with stability in rougher water. The booms cannot be towed at a speed of greater than 1-3 knots without significant losses through the boom.

Boom placement can be a huge issue in protection of an area. Booming should be deployed at an angle to the shoreline (lake, river, or ocean) in a chevron pattern, in layers, to direct the spill toward collection areas. Wind, wave, and currents along the shore and at shallow sea depths will affect the placement of the booming for effective spill recovery. The ultimate purpose of booming is never to prevent the chemical or oil from reaching the shoreline but to minimize it and recover or contain the spill and protect shoreline exposure as far as practical. Booms cannot provide 100% protection from oil or chemical spills or leaks, but they can minimize the impact of those events.

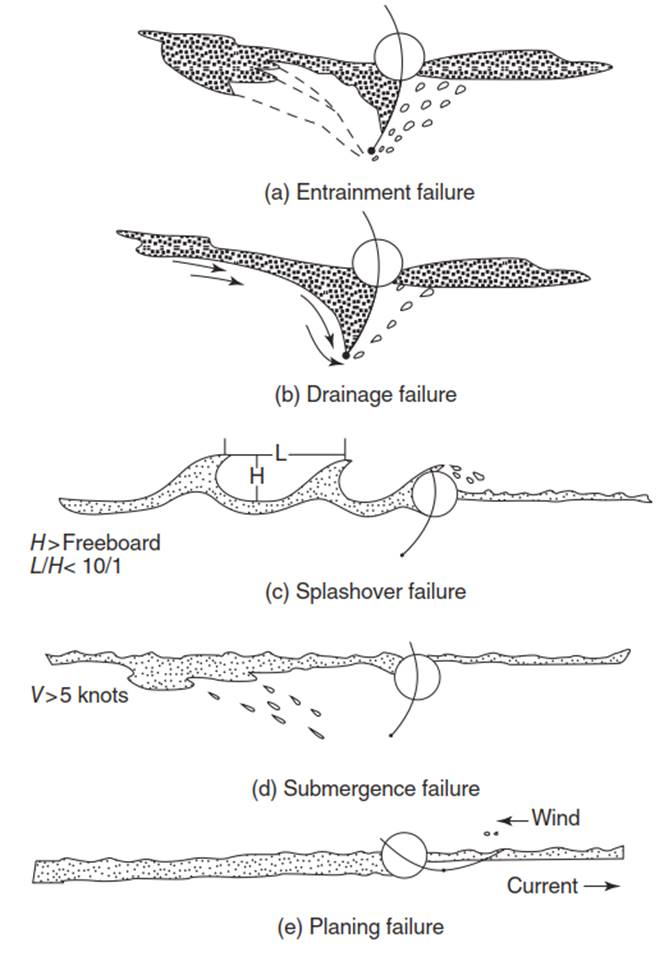

Figure 3 is taken from the Booming Manual6 cited above, and it illustrates the five ways in which oil booms fail during use. Those methods are entrainment failure, drainage failure, splash-over failure, submergence failure, and planning failure. Planning failure is one of the most difficult to compensate for because in open waters, currents and winds often shift, causing the boom to pass oils and other floating chemicals.

Figure 3. Types of oil boom failures

Effective boom placement is a combination of experience and science. In fast-moving rivers, booms are primarily set in chevron style overlapping patters at an angle to the current. For fast waters, a chevron style deployment pattern is used in an effort to divert the spill to one specific location on the bank where it can be recovered more easily in a “quiet water" area created by the booming.

Booming, which is used for protection of shoreline or structures, often requires a substantial “sea anchor" offshore to prevent movement and wash up upon the shore or river bank. Multiple heavy anchors are required for boom stability, depending upon the length of the containment. The shore protection booms are deployed far enough out from shore so that waves are not breaking over the boom.

Anchorage of the boom to the shore is also very important for protection of the shoreline. The shore boom is connected to the sea boom and has one end anchored, well above high tide, and beyond the point where minor rough weather will not dislodge the anchor. Many of the shore booms are partially buried for stability at the point of contact with the shore to provide additional anchorage for the boom.

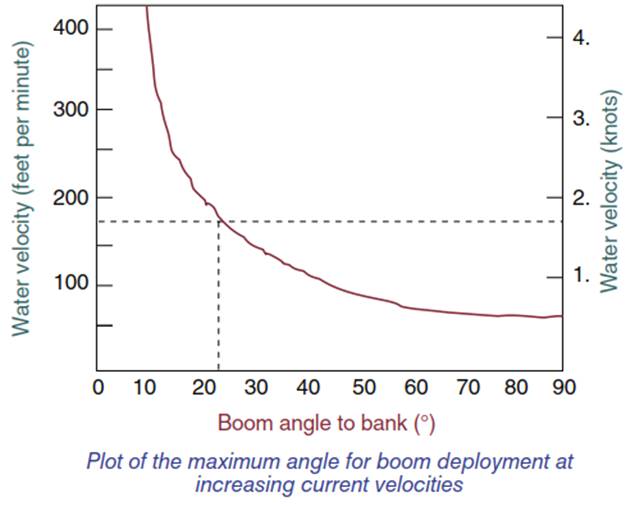

The placement of a boom in a flowing river depends upon the geometry of the river channel and the velocity of the water. For very quiet rivers, the booming can be essentially perpendicular to the direction of the flow. The angle of placement increases with the speed of the current to approximately 10° to the normal direction of the current for faster moving waterways. Guidance on boom placement can be found in the documents referenced in Endnote 7 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Booming angles for various current speeds in flowing water

In instances where the oil or chemical spilled is thicker, and flammable, the easiest method of cleanup is to set the layer on fire to destroy a significant amount of the floating material. This requires special “fire booms" able to withstand the heat while maintaining their shape and buoyancy. Fire booms are often deployed around a spill in the open ocean where the oil is thick enough to support combustion.

Spill control booms are imperfect instruments for containing oil and chemical slicks in open waters and wherever there is a combination of wind, wave, and current actions in open seas or near shorelines. Booms are often the best tools we have available to contain and cleanup a spill.

Date added: 2025-01-04; views: 371;