Rome, Catacomb of Callistus and Catacomb of Priscilla

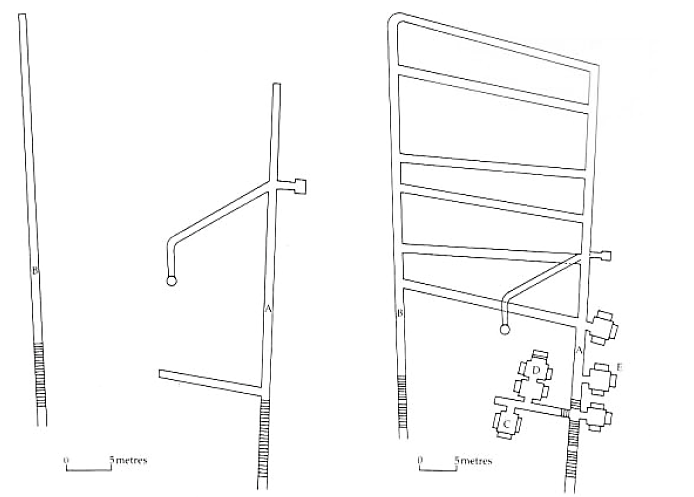

The catacomb appears to have been constructed in an orderly fashion within a clearly defined circumference (fig. 10). Firstly, two staircases were excavated and a gallery driven from each, the one nearly parallel with the other. One of these galleries (B) remained for a time merely a straight line, but the second (A) was modified in two respects: a short passage was driven leftwards from the foot of the steps while, twenty- three metres farther on, another gallery was made to run also to the left but inclining backwards in the direction of the steps and ending at a well. All this excavation dates from the period just after 200 ad.

10. Rome, Catacomb of Callistus: as it was about 200 ad, and as it became after enlargement about 220 ad. C. Cubiculum of Orpheus; D. 'Crvpt of the Popes'; E. the three Sacrament Chapels. Their number was doubled a few years later in the course of much further development

The next stage, perhaps carried out by Callistus himself, was a deepening of the galleries A and B, which were then connected by means of three cross-galleries. But the demand for space continued and, about the year 220, further works were carried out. Three more crossgalleries were constructed between A and B, and two sets of crypts formed. The short passage running at a right angle from the staircase now led to the 'Cubiculum of Orpheus' on the left and, almost opposite, to the double chamber known as the 'Crypt of the Popes'. At the same time, three crypts were excavated from the other side of gallery A, just beyond the foot of the staircase; these are the 'Sacrament Chapels'. Their number was doubled a few years later when the level of the galleries was again lowered.

The growth of the catacomb continued throughout the fourth century. Pope Damasus, in particular, was responsible for many of the alterations which sometimes embellished and strengthened, but sometimes also destroyed, the original pattern as eagerness for burial in so renowned a sanctuary strained its capacity to the utmost. The 'Crypt of the Popes' (fig. 11), like the catacomb as a whole, experienced considerable, and fairly rapid, changes. It began as a double cubiculum, irregularly shaped, in which some sixteen popes and bishops were deposited within simple, unadorned niches. One of these was set in the wall at the end, but this was soon transformed to become a table-tomb, decorated with marble and strengthened with a low wall.

11. Rome, Catacomb of Callistus: the 'Crypt of the Popes'

The suggestion, not entirely convincing, has been made that this marks the resting-place of Pope Sixtus II, who, together with four of his deacons, met a martyr's death in 258 ad. A doorway was squeezed in without much refinement at one side and a window cut to admit some light from the adjoining gallery. Later works, however, perhaps those of Damasus, destroyed this primitive but quite effective pattern. A light-shaft, driven down from above, spoilt the painted ceiling, the window was blocked up, and two barley-sugar columns, still in existence, were erected partly as decoration and partly to provide an architrave from which lamps might hang. Through such casual methods the Roman catacombs developed.

The Catacomb of Priscilla, one of the largest of those found in Rome, is rather less easily interpreted than that of Callistus. It received its name from a certain Priscilla whose inscription, with the title of clarissima, indicates that she was of senatorial rank. It has often been supposed that, belonging to the distinguished house of the Acilii, she established this burial-ground for use by members of her family and by the poorer members of the Christian community in that quarter of Rome. Recent excavations,18 however, have shown that the so-called 'hypogeum of the Acilii' can no longer be claimed as a Christian burial-place of first- or second-century date. The area originally consisted of two galleries set at right angles and approached by a staircase.

The galleries were in time subjected to a certain amount of enlargement and a sloping passage took the place of the staircase which was then blocked with a wall of brick and tufa. The longer arm of the gallery ends in a large chamber which apparently served as a water-reservoir before being transformed into a place of burial at the end of the third century; it is to this period that the earliest Christian tombs and inscriptions may be assigned. There was, however, a pagan cemetery above ground from which material fell into the catacomb passages, and the memorials to Priscilla and M. Acilius 'of consular rank' are displaced fragments belonging to the period when members of the Gens Acilia were not yet Christian.

The nearby area of the 'Greek Chapel' (fig. 12), so named from inscriptions in the Greek language painted on a wall of the main chamber, seems to have begun as the undercroft of a private house. The layout is complex, but the largest aisle took the form of a chapel ending in three recesses, resembling an apse and two diminutive transepts. The whole is richly decorated by the hands of two skilled artists, one of whom thought it right to exhibit a eucharistic feast of the type celebrated, no doubt, within the Chapel, but not earlier than the end of the third century.

12. Rome, Catacomb of Priscilla: the 'Greek Chapel'

The other main feature of the Catacomb of Priscilla is the 'Sandpit', a maze of intersecting galleries, wider than catacomb galleries usually were, and cut out of the soft stone. This seems to have been a popular burial-ground for persons of little substance; the unpretentious sepulchres are closed with rough brickwork bearing the names of the deceased or the simplest emblems of Christian hope. In the course of time the walls showed signs of collapse and had to be reinforced by crude buttresses. Subsequently the arrangement found in many other catacombs was followed and a second level was constructed, deeply sunk below the first. This consists of a very long, straight gallery, regularly intersected by side passageways containing thousands of tombs.

The Catacomb of Praetextatus follows a similar pattern in that, as is now apparent, a long and comparatively wide gallery serves as a main thoroughfare from which tributaries extend on both sides to form a maze of interrelated passages. Inscriptions point to 291 and 307 ad as relevant dates.

Date added: 2022-12-12; views: 626;