Subjects of Catacomb Paintings

The subjects of the catacomb paintings are presented in two different ways. Many scenes are drawn from the Old or New Testament; alternatively, symbolic figures are used to summarize as if in shorthand the essence of Christian hope. The symbols may, in their turn, be divided into those representing Christ and those which stand for mankind—or, rather, for the individual soul rejoicing in the prospect of eternity. Much of the imagery, however, while amenable to a Christian interpretation, is drawn from a common stock of general themes suggesting the bounty of nature and the graceful circumstances of country life.

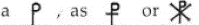

Of the various symbols, the cross is perhaps the most important. But in the catacombs, as in Palestine, this is really a mark of transition; the taw, reminder in Old Testament times of God's saving mercy, is transformed into the cross of Christ, which dominates the New Testament. The cross appears in many forms: the long Latin cross  , the Greek cross with equal arms

, the Greek cross with equal arms  , and occasionally, as in the Catacomb of the Jordani, the swastika, adapted for western purposes after long use as a religious emblem in the East. Again, as in Palestine, the cross can be shown in combination with

, and occasionally, as in the Catacomb of the Jordani, the swastika, adapted for western purposes after long use as a religious emblem in the East. Again, as in Palestine, the cross can be shown in combination with  , when it conveniently summarizes the name of Christ. Or it may be merely hinted at through the forms of anchor or trident.

, when it conveniently summarizes the name of Christ. Or it may be merely hinted at through the forms of anchor or trident.

The fish, with its varied history as a religious symbol in Egypt and other lands, was readily adopted into Christian uses, serving both for Christ and for the believer. By a happy accident the Greek letters  , which spell the word for 'fish', can be interpreted as an acrostic making up the initial letters of the phrase 'Jesus Christ, Son of God, Saviour’. This, when taken in connection with references to fish in the Gospel story of the miraculous feeding of the multitude, made it easy for Christians who partook of the eucharistic bread and wine to think of themselves as receiving through faith the body of Christ, described allusively as the fish.

, which spell the word for 'fish', can be interpreted as an acrostic making up the initial letters of the phrase 'Jesus Christ, Son of God, Saviour’. This, when taken in connection with references to fish in the Gospel story of the miraculous feeding of the multitude, made it easy for Christians who partook of the eucharistic bread and wine to think of themselves as receiving through faith the body of Christ, described allusively as the fish.

The epitaph of Abercius, bishop of Hieropolis in Phrygia, contains the words 'Faith has provided for us as our food a Fish from the fountain, mighty, pure, one whom a virgin brought forth', and a gravestone from Autun retains this eucharistic reference in the words 'Eat when you are hungry, receiving the Fish in your hands.' Such references find their parallels in catacomb painting. Thus a diminutive wall-painting in the Crypt of Lucina shows a fish swimming along with a basket of loaves on its back (fig. 15).

15. Rome, Crypt of Lucina. Wall-painting: fish and basket of loaves

In the middle of the basket and beneath the five loaves is a reddish patch which some explain as a vessel containing wine. No doubt a reference to the Miraculous Feeding is intended and, if the fish is seen as alive and swimming, the thought comes close to that of the Fathers who declared that 'Christ, himself the true bread and fish of the living water, fed the people with five loaves and two fishes’.

Allusion to Christ is also made by the representations of a shepherd boy bearing a sheep on his shoulders (fig. 16), a popular theme found about one hundred and twenty times in the catacombs. This type of the sheep-bearer is extremely ancient, being found in reliefs from Carchemish that date back to 1000 вс. Here the suggestion is of an animal being held by its four legs and carried off for sacrifice, but the Greeks transformed the figure into that of Hermes, god of compassion, or in more abstract terms, an emblem of effective sympathy.

16. Rome, Catacomb of Domitilla. Wall-painting: the Good Shepherd

The Christians had little hesitation about adapting pagan art-forms to their own uses and, in this particular case, there was an abundance of Scriptural texts to assist the process. Ezekiel had proclaimed the divine message: 'I will set up one shepherd over them and he shall feed them, even my servant David: he shall feed them and he shall be their shepherd', or, in the words of the second Isaiah, 'He shall feed his flock like a shepherd; he shall gather the lambs with his arm.' Prophecies of this kind found their echo in the parable of the shepherd who searches for the lost sheep, and their fulfilment in the discourse concerning 'the good shepherd who layeth down his life for the sheep'. Tertullian, writing in North Africa around 200 ad, spoke of 'the Shepherd whom you depict on your cup' when referring to engraved glass vessels which illustrated the theme of the shepherd protecting his flock.

At roughly the same time catacomb paintings were being produced which showed Christ not simply in realistic terms as a Galilean peasant who lived when Pontius Pilate was procurator, but with the implication that he was indeed a second David, with the power to preserve his sheep from danger and uphold them even in death. Occasionally the shepherd becomes part of an idyllic, pastoral scene, providing milk for his flock or watching over it with a countryman's staff in his hand, no doubt in the Pastures of the Blessed to which the sheep have been conducted.

One of the surprising figures that may occasionally be found in the Christian catacombs is that of the pagan hero Orpheus, who is shown rather more predictably, on an ancient relief at Delphi, aboard the ship Argo and clasping a lyre in his hands. Such was the charm of his playing that, according to the Greek poets, wild beasts and even trees and stones were attracted and pacified by him, while his presence in a cemetery is made particularly appropriate by the story that he was allowed to penetrate to the underworld and reclaim his wife Furydice.

In the Catacomb of Domitilla, for example, Orpheus appears painted rather crudely in heavy strokes of pink and brown, with his right hand raised and his left holding the lyre. Around him are gathered a lion, a camel and a varied company of animals and birds whom he has subdued just as Christ pacifies and tames the passions of men.28 Naturally enough, scruples of conscience prevented the demi-god Orpheus from finding a place in many Christian burial-vaults, but the fact that he occurs at all testifies to the willingness of early churchmen to adapt for their own purposes the best known and most attractive emblems of virtue and hope.

Other symbols of Christ include the vine, for which the Scriptures provided sufficient justification. In Ecclesiasticus the words are put into the mouth of Wisdom: 'As a vine I put forth grace.' This imagery enables Christ to proclaim 'I am the true Vine.' The Lamb was naturally suggested by another Johannine text: 'Behold, the Lamb of God’, though the formalized picture of the 'Lamb standing on the Mount Zion', a popular subject in the Middle Ages, appears very seldom and then only in so late a catacomb as that of Marcellinus and Peter.

Date added: 2022-12-12; views: 657;