Plots of catacomb paintings. Continuation

The human soul is also frequently represented as a lamb, standing in security near the Good Shepherd, or as a dove. This last emblem finds an early commentary in the eye-witness account of the martyrdom of Polycarp, bishop of Smyrna, who met his death about the year 155 ad. When the flames failed to consume the martyr's body 'lawless men ordered the executioner to approach and stab him with a dagger, and when he did this, there came out a dove' — Polvcarp's spirit flying away to seek the joys of Heaven.

But in the catacombs the more usual manner of representing the human soul is through the Orans, a figure with both hands stretched outward and upward in supplication. The Orans is usually shown as a woman of mature years, but there are occasional variations and, on a ceiling in the Catacomb of Marcellinus and Peter, scenes from the life of Jonah are flanked by four Orants (one destroyed), the conventional female figures alternating with those of young men in tunic and cloak.

The figure of the Orans was taken directly from its widespread use in classical imagery, and implied for the Christians much the same thing as it had meant for their pagan precursors. For the Orans represents pietas—the affectionate respect due to state, to ruler, to familv or to God. On coins from the time of Trajan to Maximian Hercules, throughout the second and third centuries ad, the Orans appears quite frequently, accompanied by some such motto as Pietas Publica; an assertion of, or plea for, the 'righteousness that exalteth a nation'. Piety as a state of mind naturally expresses itself in prayer; thus the Orans is shown in a prayerful attitude, looking directly at the beholder in what was considered to be the natural pose of sincere and candid spiritual power.

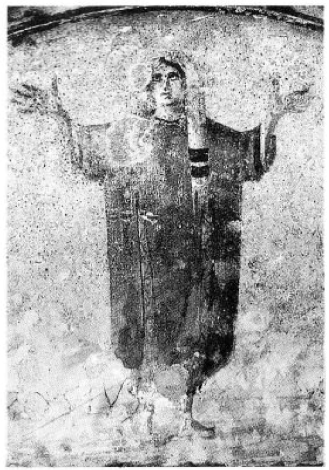

Sometimes, however, the Orans represents not piety personified but some individual rejoicing in salvation. The Brooklyn Museum collection includes a funeral stele, probably of the third century ad, on which, by means of pillars and carved gable, a chapel is indicated. Within stands a man, clothed in a tunic, facing solemnly to the front and with hands raised exceptionally high in prayer (fig. 17). His name is given in an inscription as Chaeromon, and that he comes from a Greek-speaking district of Lower Egypt is confirmed by the presence of two jackals, emblems of the god Anubis.

17. Funeral stele: the Orans

The Orans as found in the Christian catacombs maybe said to display one or other of the two emphases of pagan art. A striking figure, the so-called 'Woman with a Veil' of the Priscilla Catacomb, follows the classic pattern of pious supplication (fig. 18). Her hands, projecting from the sleeves of her red tunic, are raised, with thumbs pointing heavenwards and fingers extended, to the level of her head. The large and awkward hands may have been so drawn in order to emphasize the idea of prayerful entreaty, for the woman's face, with its touches of high colour and its deep-set, uplifted eves, shows the artist to have been a man of sensibility and skill. But he used as his Orans a recognized type which is repeated almost exactly in the Catacomb of the Jordani. By contrast the Orans in the Catacomb of Domitilla, standing in a graceful and composed attitude between two trees, suggests rather the soul at rest in the enjoyment of paradise.

18. Rome, Catacomb of Priscilla. Wall-painting: the 'Woman with a Veil'

Many other symbols were drawn into Christian service from the pagan repertory. One of these was the phoenix, of which it could be written:

Let us consider the strange sign which takes place in the East, in the districts near Arabia. There is a bird which is called the phoenix. This is the only one of its kind and it lives for five hundred years; and, when the time of its dissolution in death is at hand, it makes for itself a sepulchre of frankincense and myrrh and other spices, and, when the time is fulfilled, it enters therein and dies.

The belief that the phoenix then came to life again suggested resurrection and immortality, and it is no doubt for this reason that the phoenix sometimes appears painted in the catacombs. The most splendid example is that in the Priscilla Catacomb, with a 'crown of rays fitted all over its head, in lofty likeness to the glory of the Sun-God', and its body enveloped in jutting tongues of flame. More frequently depicted is the peacock. Its flesh was thought to remain incorruptible and thus, together with the brilliance of its new plumage in springtime, again to suggest the glory of resurrection. Peacocks were often set face to face, as in the Cemetery of Dino Compagni, with a vase, representing the water of life or the eucharistic cup, between them.

The various banqueting scenes that appear in the catacombs may be seen as the link between compact symbol and the fuller pictures of Biblical incidents. On a wall in one of the 'Sacrament Chapels' of the Callistus Catacomb seven young men recline at the sigma, or semicircular couch, in order to share a meal (fig. 19). In front of them are set two dishes, each containing a fish, and seven baskets of bread. The artist may well have been thinking of the meal by the Sea of Tiberias which is recorded in the final, supplementary chapter of St John's Gospel. In fact, there is no mention in this passage of baskets, which are more naturally connected with the Feeding of the Four Thousand, when 'they took up, of broken pieces that remained over, seven basketfuls.' Moreover the number seven was regarded, in the days of the Roman Empire, as the proper number of diners to take their place at one sigma.

19. Rome, Catacomb of Callistus. Wall-painting: the banquet

The artist of the Callistus Catacomb may therefore have been working merely from a general reminiscence of Christ's miraculous acts. However, a commentary by St Augustine, though later than the catacomb paintings, indicates the line of thought which connects such meals with life in the world beyond. Referring to the Tiberias incident, Augustine writes:

Now the Lord made a feast for his seven disciples, that is to say, from the Fish which they saw laid on the fire of coals, to which He added some of the fish which they had caught, as well as the bread which they are said to have seen. Just as the fish was consumed in the flames, so Christ suffered: He himself is the bread which came down from Heaven; and to Him is joined the Church in order that it may have a share in everlasting blessedness.

Nearby, in the same chapel of the Callistus Catacomb, is another scene which may be no more than a shorthand version of the larger picture. A man, clothed in the long mantle of the philosopher but with right arm and shoulder bare, extends both hands towards a three-legged table on which are set a fish and a loaf of bread. At the other side of the table, a woman raises her hands to heaven in the typical posture of the Orans. This woman is probably 'Thanksgiving', or, in St Paul's language, 'Blessing', who acclaims the action of Christ, purveyor of the divine wisdom, as he hallows the food which satisfied the apostles by the Sea of Tiberias. In the continuing life of the Church, this historical meal represents the Eucharist, which, as 'the medicine of immortality', sustains the believer and guarantees eternal life.

The picture therefore accords with a wall-painting found in one of the Christian catacombs of Alexandria. Here Christ is shown seated on a throne with someone on either side approaching hastily. One of the figures, named Andrew, brings two fish on a plate; the other man, now much defaced, was presumably Philip bearing the bread. At Christ's feet stand two baskets containing loaves. On either side of this scene is a group of people partaking of a meal. To the left, the marriage-feast at Cana can just be made out; on the right three people are reposing beneath the shade of trees while an inscription offers a motto for the whole rather elaborate composition: 'eating the blessings of Christ'.

When it came to the choice of subjects drawn for illustration from the Scriptures, the primary theme which painters naturally desired to emphasize was that of deliverance from peril by the power of God. As early as the beginning of the second century, the author of the First Epistle of Clement from Rome to the Corinthians alludes to grave troubles afflicting the Roman church. He instances Daniel in the lions' den and the three men, Ananias, Azarias and Misael, cast into the fiery furnace as persons who were oppressed by hateful men, full of iniquity, who did not realise that the Most High is the defender and protector of those who serve his excellent name with a pure conscience'. Thereafter Daniel, and the three companions in the fiery furnace, regularly find their place in the litanies which invoke God's aid for a Christian in the hour of his death.

The pictures in the catacombs often deserve to be examined not merely as individual compositions but as parts of a series of connected themes, and the 'Greek Chapel' of the Priscilla Catacomb provides a good example of the varied scenes that go to make up an essay on the subject of salvation. On the left wall of the entrance chamber appear first the three young men standing unharmed in the fiery furnace; opposite them the deceased man stands in the posture of an Orans as, with arms uplifted, he too invokes divine succour. On the inner surface of the arch above, the lone figure of Moses, rod in hand, strikes the rock to make water flow for the thirsty Israelites, and thus prefigures baptism as a requirement for Christian 'pilgrims in a barren land'.

On the ceiling of the chapel, the man sick of the palsy is shown cured and carrying his bed away. The Four Seasons, typifying God's bounty in the world of nature, appear on the ceiling also, together with what is perhaps another baptismal scene, while the further archway is decorated with a picture of the Three Wise Men adoring the infant Christ. The two side walls display episodes from the story of Susanna and the elders: first, Susanna surprised by the elders, then the accusation laid against her and, finally, her acquittal. This gay little story from the Apocrypha was another of the examples frequently used to illustrate God's power to save in time of need.

Proceeding onward from the nave into the first of the small chapels, the devout Christian of the third century would be heartened by a remarkable scheme of decoration. On the ceiling are four Orants, then, to the right, Daniel in the lions' den followed bv Abraham's sacrifice of Isaac, another instance of God's timely and effective intervention. The next picture, the raising of Lazarus, is clearly appropriate to a place of burial,46 while Noah in the Ark. who follows after, may be said to indicate the soul of the departed whom God is ready to protect from destruction just as he saved Noah from the flood. The series ends with an illustration of a banqueting scene, similar to that of the Callistus Catacomb but executed with greater delicacy and charm (fig. 20).

20. Rome, Catacomb of Priscilla. Wall-painting: the banqueting scene in the Greek Chapel

Here, too, seven people recline at the couch. There is nothing stiff about the figures; with their varied gestures, they are knit together in a vividly portrayed group. The food before them consists of bread and fish, together with a jar of wine. Seven baskets containing loaves, four on one side and three on the other, continue the line of the banquet. It would be unwarranted to maintain that this scene literally and directly portrays the Christian liturgy', but its eucharistic overtones would remind the faithful that the sacraments are appointed means to bring about divine assistance.

Date added: 2022-12-12; views: 699;