Sparta: Military Dominance, Agoge Training, and Historical Decline

The region of Laconia in the Peloponnese contained one of the principal Greek cities, Sparta, which sat on the Eurotas River, one of the few rivers that flowed all year. Laconia lay between two mountain ranges, the Parnon in the east and the Taygetus in the west, separated by forty miles of land providing a rich plain for agriculture. Sparta (also known as Lacedaemon) was the capital of Laconia, with villages spread out around the region. Laconia was bordered on the west by Messenia, to the north by Arcadia, and on the east and south by the Aegean Sea. Laconia, a large, fertile piece of land, led the inhabitants to work mainly in agriculture, especially the cultivation of barley. The region also had iron mines, which would be useful in commercial undertakings and making weapons.

During the late Bronze Age, the Mycenaean civilization, as related by Homer, controlled the lands from Sparta, with Menelaus as its king and Helen as its queen. The abduction of Helen by Paris, a prince of Troy, started the great Trojan War. The physical remains of the region are not extensive, but those near Sparta at Amyclae provide evidence of an ancient cult. From 1200 to 1100, the Mycenaean civilization was replaced with a new group called the Dorians. The decline of the Mycenaean kingdom occurred over time, and not because of one cause. Evidence indicates that the civilization fell due to war, pestilence, famine, or a combination of these factors.

Lead figure of a woman with wreath, late 7th–early 6th century, to Artemis Orthia in Sparta

The Dorians are said to have arisen through the Heraclids, descendants of Heracles, Eurysthenes, and Proclus, as well as from the sons of Aristodemus, the brother of the founder of Argos. After these initial invaders, there was a second wave during the tenth century, established in four or five villages around the later Spartan acropolis. Other immigrants settled throughout Laconia in independent villages.

During the ninth century, the villages around Sparta united, not just coalesced, to form the city of Sparta. What was unique about Sparta was that it contained none of the architectural accoutrements of a typical Greek polis. Although it did not have walls or the like, the city developed rapidly and became one of the earliest Greek poleis. The city-state developed rapidly and created what many believed was a balanced government. Its government took the forms of monarchy, oligarchy (republic), and democracy.

There were two kings instead of one, which provided checks and balances on one another. They were from the Agiad and Eurypontid families. Their primary function was military, as they led the Spartan armies on the battlefield. Due to their ability to check one another, it forced them to work together, or at least compromise not only with one another, but the other elements of government as well. The republic or oligarchy was housed in two groups, the Gerousia and the Ephors. The Gerousia (meaning “body of old men”) was an elected council of twenty-eight old men over the age of sixty and the two kings; it decided what policies would be presented to the assembly and examined other important matters. Since they were seasoned and experienced, their advice was often followed, especially when advocating against sudden or rash adventures. The five Ephors were elected yearly and had broad-ranging powers over the kings and the council. Since their power was so extensive, they could only hold the office once during their lifetime.

The democracy element was the assembly or apella (ecclesia), which ostensibly decided all important matters. It was the final authority on all issues, and their voting was done by shouting, which was then interpreted by the Gerousia. The assembly was made up of all Spartans or Spartiates who were free-born citizens over the age of thirty. There were 9,000 homoioi (equals), who enjoyed parity before the law and held their own kleros (allotments) of land to provide support them. These citizens were the hoplites of the Spartan army, divided into five lochoi (companies) from the five Spartan tribes or obai, which had replaced the original three Dorian tribes. The Spartan army became the most feared group and built upon the new Argive model.

The Spartiates were viewed as equal, not in economics or influence, but before the law and in status. These were distinctions not seen in other Greek cities. In many ways, the city of Sparta was a pure democracy, where all its citizens had the same rights and prestige. The Spartans were very protective of their citizenship; the number of full citizens or soldiers rarely increased but rather remained stable during the early Classical period before declining in the late fifth century. Below the rank of Spartiates were probably other Spartans who were not yet thirty or who had been demoted due to their inability to support themselves or other issues; as a result, they had no political rights; they were referred to as Inferiors.

Below the Spartans was a group of individuals classified as neither slaves or citizens. These individuals were named the perioeci (meaning “dwellers around” in Greek) and probably reflected the original inhabitants, who may have been the elites and were now reduced in power. These individuals kept their own villages in and around Laconia but gave up all political freedom. They also engaged in commerce and provided Sparta with the merchants needed to interact with the outside world. They could also be organized as hoplites fighting in the army, but their status was not equal to the Spartiates. Below them were the helots. Although they had no political rights and could be ordered about by the Spartans, they were not slaves in the truest sense since they could not be bought or sold. Rather, they were more like later serfs, who were tied to the local farms, working them and paying half their produce in rent to individual Spartiates. They were probably the original inhabitants of the region when the Dorians invaded and took over Laconia.

When fully developed, the Spartan system, the agoge, was highly regimented. At birth, a child was examined by the elders to determine if there were any imperfections; if so, the child would be abandoned. Males began their regimented life at age seven, when they were placed in a herd, where a Spartiate supervised them. At thirteen, they then went into another herd, where they remained for the next fourteen years, moving up through the combination of state-controlled schools and military formations. Since age seven, boys were no longer living with their families and were brutalized. They became part of a small unit, the bua, or a squad that joined together with other squads into a larger unit or troop called an ila, commanded by an eiren (a senior youth), who was under a paidonomos (senior commander).

At age twenty, a youth would become an eiren and engage in military training. As yet, these boys were not full citizens. As their main training, they would enter the famous military messes or dining associations, called the pheiditia or sussitia. These clubs became the bulwark for the Spartan military and social organization. Entrance into the club required a unanimous vote of the roughly fifteen members. The mess was known for its horrible food; it was financed by deductions from their families’ land, and failure to pay such bills could result in them being blackballed, demoted to Inferiors, or delayed in their promotion to the next level.

The youth remained in the mess until age thirty, when they became full citizens. Their sole function during this time was to train as military men. They did not have to worry about working in the fields; instead, they would join a professional army. They would train and fight with their mess mates and become a cohesive fighting unit.

As related in antiquity, the Spartan system promoted a type of homosexuality in which the elder trainers or lovers (erastes) took under their guidance a younger lover (eromenos) not only as a teacher of military arts, but as a lover. The elder was held responsible for the younger man’s behavior and performance on the battlefield. While the Spartans stated publicly that this was not a sexual system (in fact, any sexual act would be punished), that was probably just a cover-up.

A Spartan man was expected to marry around age twenty. The woman had the right to pick her mate. She would cut her hair and put on men’s clothes, and then she was placed on a hard bed. The groom would then come in and have sexual relations with her before hurrying back to the men’s barracks. Many times, they would only see each other secretly until a child was born. At age thirty, the man could return to his house, but he often continued to live in the barracks. A man who did not marry was often shunned and even penalized. Spartan women had many rights.

They could manage their own property and act for their husbands in their absence. They could marry when and whom they wanted, and when married, they had extensive freedom, much more than any other ancient society. In addition, since the state needed to promote more children, Spartan women could take lovers, including helots. To keep the helots under control, the Spartans created the krypteia (secret police), who were responsible for ferreting out discontent among the helots. They often made an example of malcontents by killing them.

Sparta did not have traditional coinage as other Greek cities did. It did not use silver but rather used iron bars as currency. This often gave rise to Spartan commanders taking bribes so as to enrich themselves and have luxury items when abroad. The bribes also allowed them to have funds in case they needed to flee Sparta and live abroad. The Spartans nevertheless were known at least until 500 for their fine workmanship in art, especially in bronze.

The Spartan system did not spring up immediately. Early in this history, the Spartans expanded west into Messenia, where they subjugated the inhabitants in the First Messenian War (740-720), making them helots. In the seventh century, they faced a struggle with Argos, which defeated them at Hysiae (669), and then with Messenia in the Second Messenian War (660-650). This probably prompted the use ofperioeci in the army. In the sixth century, Sparta faced a harsh struggle with Tegea, where after an initial defeat, they won the war but enacted a new policy instead of seizing their land as in Messenia. Sparta made a treaty binding itself with Tegea.

They were now allies, and Sparta became heroes for eliminating tyrants and protecting the Peloponnese from Argos. This new policy created “the Lacedaemonians (Spartans) and their allies,” which became better known as the Peloponnesian League. The ultimate achievement occurred in 546 with the Spartans’ victory over Argos, which secured their leadership and military dominance. Sparta continued to be known as the Tyrant Bashers, as they systematically removed tyrants from power, including in Athens, where they forced Hippias to flee into exile in 510.

With these victories, Sparta became the most important military power in Greece. In 499, the Ionian cities rebelled against Persia. The rebels sent a delegation to Sparta for help, which was refused. When Persia retook Ionia, Persia sent ambassadors to Western Greece in 492 to demand submission. The Persian ambassadors were killed at Sparta. In this period, the Spartan king, Demaratus, was exiled and arrived at the Persian court. He had fought the other king, Cleomenes, in several conflicts, including punishing Aegina in 492 for submitting to Persia. When Persia attacked Athens in 490, the Spartan army did not move north in time to take part in the Battle of Marathon. The Spartans were celebrating a major feast and did not move until after the battle, when they arrived a few days later, there were many Persian deaths to assess.

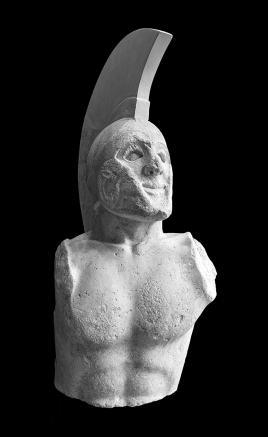

Statue of a hoplite known as Leonidas, found in ancient Sparta

During the interwar period, the Spartans had as their king Leonidas, the halfbrother of King Cleomenes, who was dethroned due to his insanity, which promoted anti-Persian sentiment. When Xerxes attacked in 480, Leonidas marched north with his bodyguard, 300 strong, to defend the pass at Thermopylae, while the main Spartan army waited for a religious festival to occur, similar to what had happened in 490.

The Spartan army once again showed the superiority of the Greek hoplites against the Persian minimally armored troops. After the Greek victory at Salamis, the allies decided to plan the next major stage in the war. The Spartans and their allies began to build a wall across the isthmus at Corinth.

In 479 the Athenians urged the Spartans to bring their army north to fight the Persians but the Spartans informed the Athenians that they had to celebrate a major festival. Athens, frustrated at the delay and inactivity of Sparta, indicated to the Spartans that they might join the Persians as allies, submit to them, or evacuate their city. Pausanias, the regent to Leonidas’s son, convinced the Spartans to move north, and in 479, over 100,000 soldiers from the Peloponnese arrived at Plataea near Thebes and defeated the Persians. Pausanias attempted to lead the Greeks against the Persians in the north, but his arrogance forced his recall, and Sparta gave up leadership against the Persians.

The Spartans moved to isolationism. The helots rebelled in 462, and the Spartans asked Athens for help, and it sent Cimon; he was then sent away, and Athens was humiliated. Sparta during this time remained inactive in combating Athens. Ultimately, the allies of Sparta forced them to go to war against Athens in 431, in the Peloponnesian War. This war, lasting from 431 to 404, finally saw Sparta come out on top after a brutal war. The period after the war led to Spartan expansion and control until a coalition of Thebes, Athens, Corinth, and Argos confronted Sparta in the Corinthian War (395-387). The conclusion led to the King’s Peace, in reference to the Persian king Artaxerxes; but it also resulted in Spartan dominance, which lasted until Thebes defeated the Spartan army in 371, leading to the breakup of the Peloponnesian League. This latter campaign led to the freeing of the helots and the destruction of Spartan power.

During the next forty years, Sparta attempted to regain its power, but without success. Sparta’s power rested in its strong military. When the population declined, Sparta’s power likewise declined. Without the ability to increase its population, Sparta became less and less capable of domination.

Date added: 2025-03-21; views: 422;