The Daily Disciplines that Help Students Learn Compositional Craft

The art of composing is different in many ways from the art of learning to perform. I am a flautist. In those lessons I was given specific sections or pieces of music I should prepare for the following week, and I spent time focusing on the mechanics of playing my instrument. But I was never worried about creating what music I should play. It can be a rather frustrating thing to sit down to compose and walk away with . . . nothing.

Nothing done, nothing to show, nothing that can be seen or heard by another person. How do you prepare for a composition lesson if this can happen? How can your student feel they are progressing and stay inspired? In this section I will describe an approach to preparing for the weekly lesson through a daily plan. This model assumes a one-hour composition lesson each week.

Recognize What Constitutes the Work of Composing.Students often make the assumption that composing a certain number of measures equals success for the period of time they spent composing. This is only true if those measures are worth keeping in the final score. Like the flute example above, a certain amount of daily time spent working is beneficial but only when students understand what that daily work entails. Unlike the flute example, a teacher cannot assign a certain section of music or number of measures to work on weekly.

The amount of music composed will vary from student to student and also in relation to how far along the new score has progressed. With that in mind, do not assign a certain number of measures to be composed each week. This is not practical and is potentially harmful. A teacher would never say out loud, “another student composed 45 measures this week, so you must not be trying very hard or spending enough time composing.” Students, however, are likely to make these comparisons on their own and then develop the belief that they must spend hours working to produce the few measures assigned. It is this negative narrative of implying we are all able to produce the same amount of work each week that creates attachments to the much beloved melody mentioned earlier—the one they are unwilling to edit under any circumstances. Rather than ask that a certain amount of work be produced, teach students that the time spent is the work, then teach them how to spend their composition time wisely.

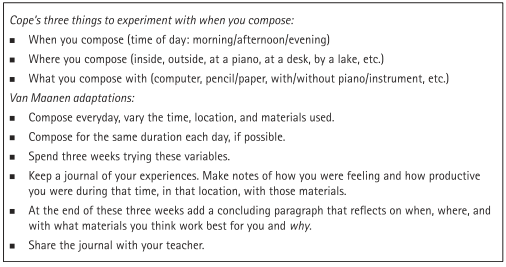

Learn to Work Smarter.Composers can learn to work with great efficiency. Recent brain research suggests that working for shorter bursts of time generates creative productivity with the highest retainable output (Kaufman, 2019; Beaty, 2020). The first assignment I have given my private lesson students for the past fifteen years is an adaptation of an activity featured in David Cope’s Techniques of the Contemporary Composer (1997, p. 11). Shown in Figure 24.3, this activity engages students in a self-assessment of their work environment.

Figure 24.3. Composer practices: A self-assessment of work environment

It does not matter what students compose or how much material is produced during this activity. This assignment is about empowerment. Students need to feel like they are in control of their environment which, in turn, will help them produce creative results. Once they submit this assignment, we have a group discussion and share what they learned about themselves. They are amazed at how many differences there are between them all! Students discover a feeling of freedom when they realize they do not have to compose in a manner like someone else to be successful.

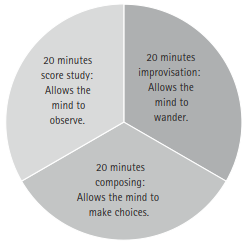

Establish a Routine.Self-assessment of one’s work environment is just the first step toward developing a daily compositional practice routine. Students must compose every day and, if possible, compose on a schedule (Lally & Van Jaarsveld, 2010). I require students to compose five days a week—they decide which days. As many composition students are also performing musicians, they know how to use routines for practicing their own instrument, but it might not occur to the new composer that this model could be a useful tool to help them grasp the daily discipline of composing music. Figure 24.4 presents a model for dividing one hour of composition practice time into three focused activities. These form the bulk of compositional practice and when done as a routine help composers recognize their success and loosen their grip on the material that needs editing. It is worth noting that the hour of suggested time is meant only as a starting place for those students who struggle with time management. What is most important is that the amount of time be the same each day to create a sense of continuity.

Figure 24.4. Model of daily compositional practice

This model is adaptable and should be used on a sliding scale. If, for example, a student is planning to compose a new piece, the hour might be spent fully engaged in score study for two to three weeks as you and the student delve into specifics about how to compose for the certain instrumentation.4 (Score study will be addressed later in this chapter.) After this initial score study phase, students might improvise a page or two of ideas for their lesson, or two lessons if needed. This gives the student the ability to choose the ideas they are most attracted to and you an opportunity to help them determine which ideas show the greatest promise for longevity. You can, at this point in their development, try the skeletonizing exercise on their ideas. Be responsive to the needs of your individual students: A fast writer will be able to do more; let them. A slow writer will struggle to come up with one page—and that is fine. Acknowledge their accomplishment.

When students are in the midst of composing, the 20/20/20 breakdown is most effective. If they get writer’s block, they move to score study or improvisation. If they are on a roll, they compose. The point to be made is that there is always a task they can be working on even if they are temporarily stuck. If the student is in the final section of composing the piece (meaning approximately two-thirds of the way through or more), that hour should be focused on composing as score study and improvisation may not be needed during this time. The segments of the 20/20/20 routine do not need to be completed in a single one-hour block. Students can take breaks, as these are shown to improve creativity. Walk away for five to twenty minutes in between work sessions, or work for 20 minutes in the morning on one task and return in the evening for the final 40 minutes of work. These breaks, however long, provide time for reflection.

Private Study.Composition lessons, with individuals or in classroom settings, should reflect this daily routine. Students often only want to show you their musical products but encourage them to take you through their weekly work, including material that they discarded. Ask how and why they made specific choices to keep certain ideas. Their descriptions give them practice discussing their music and will be useful in college auditions. Invite them to identify where they need help and tackle those spots. If you believe there is a problem area and they do not raise it, ask them to describe their work in that spot. Explore it together without judgment. Should students not produce enough work to fill a one-hour lesson, spend time modeling score study (discussed later in this chapter) or address other topics (i.e., counterpoint or orchestration) that may inform their work.

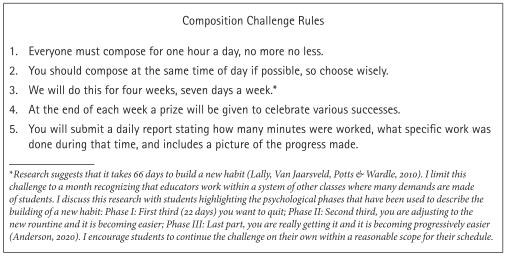

A Composition Challenge.I introduce my 20/20/20 model with students in a composition challenge that happens each October in my studio. I specifically choose October so that school is settled, parent conferences are behind us, and the days are rolling along nicely with routine. This challenge originated with Professor Jamie Leigh Sampson and Dr. Andrew Martin Smith, both at SUNY-Fredonia. Professor Sampson initially came up with the idea of modeling a composition challenge based on a podcast about learning to run called Couch to 5K. The challenge essentially eases students into what to do while composing and complements the daily routine I teach. I have adapted their collegiate challenge for high school students as shown in Figure 24.5.

Figure 24.5. Composition challenge rules

I keep a record of both my individual students as well as the whole class for inspiration, and I send daily messages of encouragement. I also do this challenge with them and they can see my work alongside their own work. At the end of the month, I take my studio out for dinner to celebrate. There, I talk about the progress I saw in all of them and ask them what they learned from the challenge. I record and share their average number of minutes worked per day. We repeat the challenge for a “pick me up” in March, but only for two weeks, due to other academic demands. At that time, I ask each of them to strive for their personal October average per day plus ten minutes.

This challenge is amazing because it gives students a starting point each day! They begin to believe they can create new music every day, and this reinforces the idea that the music composed today is dispensable because more will follow tomorrow. It empowers them to let go of their ideas without worrying about finding something new. It also separates them from the idea—an idea can be good or bad without the student feeling they are good or bad as a composer. Students become excited to engage in meaningful conversation about their work (without tears, wringing of hands, or ego-bruising). Most importantly, a deeper sense of trust develops as students realize that teacher feedback is not meant to criticize them but intended to instead advance their compositional skills. As a bonus, college composition faculty will be impressed by an interviewee’s ability to calmly discuss the process they went through to create material, how they decided what material they would keep and why, and how they edited and developed their musical ideas.

Date added: 2025-04-23; views: 180;