Score Study. Routine and Guidelines for Score Study

Helping the student find their compositional voice requires acknowledging who they are as a person, determining what they want to express through their music, and helping them figure out how to compose music that reflects just that. Focused score study can help students not only strengthen their craft, but also find their own artistic, musical voice. This process takes time, even years, but with high school students it frequently means gently nudging them away from Mozart or that favorite film/video game composer they are emulating—the comfortable pieces they already know—toward an experience that introduces them to hundreds of new pieces and composers. Score study will broaden their base of musical knowledge so that new ideas which are uniquely theirs, can emerge.

Connecting students to new (to them) music is easy. The number one go-to resource for my students is YouTube. To be fair, they find some pretty amazing pieces on that site. However, they need access to physical scores, not just videos/recordings. I usually strike a bargain by saying: “I’ll listen to one piece that you find on YouTube if you listen to/look at a physical score for every three pieces I suggest" They always take the deal. They like to show me what they find, so I learn with my students. They adore that part of our lesson.

Once students get into score study, they fall in love with it because they are starving for this information. The scores I choose for students fall into three categories:

- Resource: A score that is pertinent to the development of the current piece the student is composing and helps them solve a problem. Make this a score they can understand easily (draws on their knowledge of music theory or has some other familiarity).

- Exploration: A score for the sheer joy of discovering something new. There is not a specific connection to the piece they are currently composing.

- Challenge: A score where the harmonic language, texture, or other elemental usage challenges your student in some way. Consider choosing scores that are based on texture rather than melody, for example

The score that is selected is key. As Ponsot and Deen have noted, “Observations go between the naive and the critical response. But they also begin the analysis, the loosening of the order of the work the student is reading” (1982, p. 161). Score study should not only be concerned with traditional analysis of a musical score. It is about observing what is possible. When you suggest score study, students will want to impress you with some deeply profound psychological aspect of the work that they found on Wikipedia absent the specific knowledge of the technical workings of the piece or the reasons why the composer made the choices they made. Students do not know how to simply observe the score; you must teach them the skill.

Routine and Guidelines for Score Study.To engage in score study requires the development of the language of observation. This is particularly important in pedagogical contexts as teachers and students need a shared language to talk about music. Harvard’s Project Zero6 offers two thinking routines that advance this skill set: “See, Think, Wonder,” and “Color, Symbol, Image.”

Routine I: “See, Think, Wonder”. This exercise invites students to look at a page of score and simply state what they see, what they think about what they see, and what it makes them wonder (Project Zero, 2016). “I see” can be changed to “I hear” if students are listening without score. The goal is for them to state clearly what is they see/hear. You will be surprised at how many students cannot do this exercise. They would prefer to ponder the deep meaning rather than state the obvious. For these students I will start with leading questions or statements like:

- Describe the dynamics you see/hear. How/where do they change?

- What is the rhythm of the main motive you have been talking about?

- How does that rhythm change on page 1? On page 2?

- Why do you think the composer made those decisions?

Once students understand the simplicity of the process, they are able to grasp the concept. The observation that happens helps students understand (see) how much detail is needed in their own composition. Without you saying “add more dynamics” they will start to do just that.

Along with “See, Think, Wonder,” I have students engage in score copying. On staff paper, with a pencil, they copy out one to three pages of their favorite score. They must use a ruler and line up beats, produce straight bar lines, etc. In copying the work, they engage in a sustained attention that requires quality of focus (Ponsot & Deen, 1982). This work allows them to notice everything and absorb what is on the page deeply and with true understanding.

Routine II: “Color, Symbol, Image”. After listening to a new piece of music have you ever asked a student to respond only to be met with “I liked it” or “It was pretty”? Beyond that statement, they cannot articulate further what they liked about it, what was pretty, or how the composer created the “pretty” aspect. If pushed, students become frustrated because they cannot think of any other way to describe the music. The problem is twofold: a single listening is not sufficient for the brain to process all that happens in a composition, and students need a vocabulary for describing what they have heard.

The first task in vocabulary development is identifying the terms they already know and can use. “Color, Symbol, Image” asks student to:

- Pick one section of the music and choose a color for it that best captures the essence of that idea.

- Pick a different section of music and choose a symbol for it that best captures the essence of the idea; and

- Pick a third section of music and choose an image that captures the essence of this idea.

After the initial listening, students work in pairs or small groups and describe to each other how their choices represent each musical section. “The idea is to simply find some common ground that can be used to communicate about the piece”7 (Project Zero, 2015). Students who previously could not describe music on first hearing will now be describing detailed images of what they saw/heard as the music was being played. This exercise works best with unfamiliar pieces selected to challenge students in some way. Further listening results in deeper observations and descriptions.

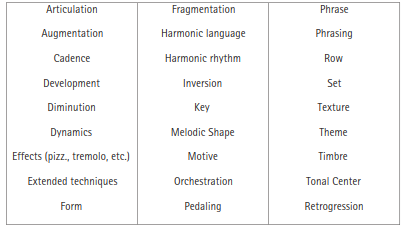

Using Routines I and II. “See, Think, Wonder” and “Color, Symbol, Image” can be used for a few weeks or even months, interchangeably and together, depending on the progress of the student(s) in any composition instructional setting. Once students have gained a degree of comfort with these routines, we move on to the music-specific vocabulary shown in Figure 24.6. The discussions that happen once this music-specific vocabulary is in place will result in more detailed observation of content. Students now possess the vocabulary to describe the specifics of what a composer has chosen to do in their piece.

Figure 24.6. Vocabulary of some compositional terms for study (listed alphabetically)

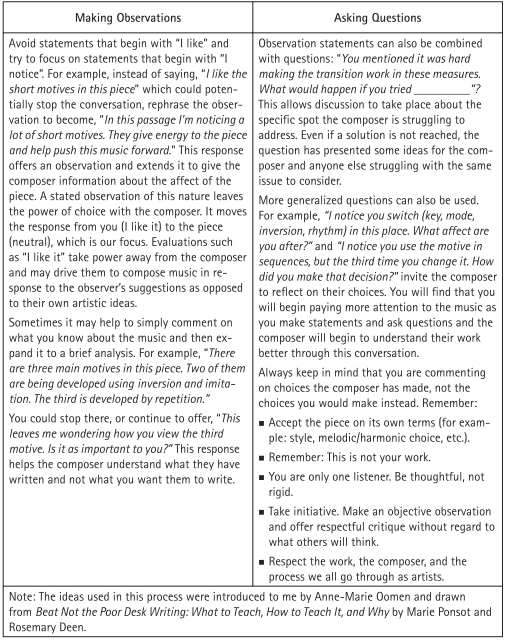

Routine3: Observational Critique. Once students have reached this ability in our score studies, we are ready to add the process of sharing in-progress student works. This new activity, often taking place two to three months into the score study process, will require students to use their newly acquired vocabulary while adding the skills of giving and receiving constructive feedback. Begin by discussing what critique is and how it contributes to growth. Introduce the “Ladder of Feedback” as a helpful tool for organizing four aspects of critique: “1) Clarify: ask questions to help you understand fully; 2) Value: Express what you liked by giving detailed examples; 3) State concerns: Kindly express your concerns; and 4) Suggest: Make suggestions for improvement”8 Encourage students to balance each concern with an idea, suggestion, or possible solution. (Project Zero, 2018)

As students listen to each other’s work, they should be tasked to consider their own compositional challenges. Ask them to focus on a single issue and consider how the presenting student handles the same challenge. If they cannot think of a challenge in their own work, encourage them to select a topic from the vocabulary list shown in Figure 24.6 and observe that topic as they listen. Students may also use the techniques from “See, Think, Wonder” or “Color, Shape, Image” to help focus their attention. Now that students have ideas they wish to express about others’ work, they can use the ladder of feedback to share their thoughts constructively. In addition, Figure 24.7 provides a brief overview of how listeners can articulate observations and pose questions such that the power of choice remains with the composer.

Composers open the sharing process by introducing their pieces and presenting a problem they are currently working to address (i.e., a tough transition from the A to B idea). Students then play the work, often via MIDI playback, and invite comments. As feedback is offered, composers are encouraged to listen, not react. The goal of the exercise is to empower the composer by becoming more informed about their work so that they can make good choices as they strive to attain compositional goals. When critique sessions are properly facilitated by the teacher, students emerge excited to compose and have gained many ideas about how to solve the problem they presented to the group. Most importantly, taking time to discuss compositions-i n-progress allows all composers to become more articulate concerning their music and artistic vision while they acquire the information needed to make that vision a musical reality.

Figure 24.7. How to critique a composition through observation

Date added: 2025-04-23; views: 208;