The Problem of Confidence as related to Composing

The first thing I want to address is the high school ego and adolescent psychology, and how these impact a students’ realistic observation and editing of their work. The level of confidence in students greatly affects their ability to see their product realistically and make artistic changes that strengthen it. They can easily fall in love with their first draft and be averse to changes for a couple of reasons.

One is fear—a lack of self-confidence and not knowing what to do next. A second is overconfidence— imagining it is the greatest thing ever composed. Most of these students are averse to change simply because they have not had the opportunity to familiarize themselves with more possibilities (score study and knowledge of living composers for example).

I am certain that the challenges of the high school ego are familiar to anyone reading this chapter. Students of this age want to be seen as independent and able to act on their own decisions, and they like to showcase their abilities. Their confidence can be strong, weak, or hover between the two.

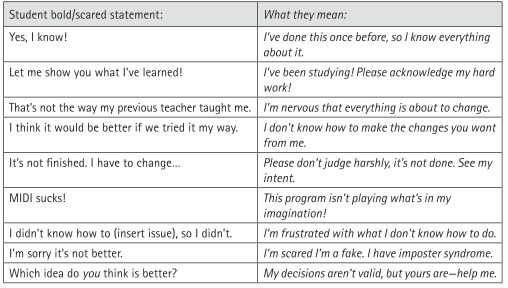

Because I work with teenaged artists, I find the extremes of this range are more common. Regardless of where students sit on this continuum, they need guidance that shows them what they need to learn without either bursting or exaggerating their confidence. I frequently hear the following bold/scared statements, translated in Figure 24.1 to reveal their true meaning, that help me gauge the level of confidence of my students.

Figure 24.1. What students’ bold/scared statements really mean

Overconfidence.Sometimes a student’s identity is strongly tied to “being right.” This story provides an example of a situation and a strategy for working with an overly confident student so that they might grow.

A student (junior) composed an orchestra piece using Sibelius with MIDI and had altered the dynamics artificially. The harp was marked “ffff” and the mid-high ranged brass was “mp” The rest of the orchestra was situated in mid-low registers, but in full force dynamically. I began to comment that the mid-low range harp and flutes would never be heard. Before I could finish my sentence, however, this student interrupted insisting that it would be fine2. He said that our two harpists could play out more and all would be well. I could easily have shut him down with examples of why he was wrong, but I knew that would entrench his insistence on being seen as “right” What I recognized in this young person was that he needed to BE right. His ego and cultural background depended on it.

Rather than show him where his thinking was misguided, I took a different tactic. I asked him to describe to me the sound he wanted to hear. He is part of our orchestra, so he had direct experience with balance. As his description went on, we would stop and look at the various sections of the music in small chunks. The more he described his sound and the more he observed his work an evident change in his confidence started to take hold. He became skeptical of certain areas of the music but kept his confidence in others. Eventually he came to realize that I had walked him into the idea that “the harp and flutes will never be heard” on his own. We had a good laugh and he apologized for interrupting. This student walked out of his lesson knowing what I hoped he would learn, but more importantly kept his confidence about things that were solid.

Lack of Confidence.Students who lack confidence often seek “in-between” moments—those times that occur at the end of the day, between classes, or whenever you feel rushed to be elsewhere—to ask their questions. They murmur questions like “If you have time, would you tell me if this is good?” in tones that suggest they do not want to bother you. Hearing these, we are tempted to reply, “If you’ll come back during office hours or make an appointment,” or worse, we take a quick look and respond too abruptly with “Yeah, that’s good but it would be better IF . . .” because we are in a hurry. For a student with plenty of confidence being put off until another time is fine. They do not take this gesture personally. For students who are lacking in confidence, however, this response is “proof” that their art is not good enough.

Lack of confidence can cause a paralyzing fear for any creative artist, including composers. Students may begin to struggle with choice of notes, rhythms, harmonies, etc. Simply spending time with these students and answering even one question can make all the difference in their confidence level as is shown in this story:

A student who had been working with me for about a year and a half was sitting across from me in my office during her lesson. We were (I thought) editing a finished piece for the layout of her score on the page. I was making comments about placement of dynamics, addition of articulation—the usual polishing notes. When I looked up, she was sitting very still, in tears. I was floored, lost. I stopped talking and sat still for a minute. She eventually started apologizing and I when I responded with “You have nothing to apologize for”—more tears.

After a little time had passed, she was able to talk, and we decided to go for a walk around campus. What eventually emerged was that she felt everything she did was wrong. She felt this way because I was always commenting on what she should change. I realized she was unaware that I thought her music was very strong, very good! She did not know, because I had not made it obvious: the reason I could make detailed comments on her work to the level I was doing was because her music was so very well written. I learned a lot that day. I learned that for everything I say that could be perceived as a negative, I needed to be sure to bolster it with what is working in the music (Marano, 2003; Zenger & Folkman, 2013).

Date added: 2025-04-23; views: 188;