The Craft of Composing Through Learning to Edit

Students often fall in love with their first draft. For example, if a student’s melody is not good—for whatever reason—saying so can crush their spirit. They have searched long and hard and high and low for this melody, and this is IT. This is the ONE. These same students also compose eight bars and think they are automatically measures 1-8. They also assume their next four bars are measures 9-12.

Once those measures are done, they must search for new material to follow. And, so, it goes. Because they have worked so hard, they believe these measures are set in stone. Students fear that cutting material will leave them without ideas and wonder how they will ever replace what they have cut away. Making any suggestion about altering their work is both an affront to ego (“.. but I’m amazing, how dare you suggest..” or “I knew I was never any good”) and incitation of fear about creating more musical material. At this point, students need to learn that editing does not mean that their musical ideas were bad. Editing and rewriting are tools that can get them even closer to their artistic ideal (Ponsot & Deen, 1982).

To teach the craft of editing, I use a concept I call “skeletonizing" It is loosely based on Schenkerian analysis, but from the point of view of creating material. Its goal is to generate musical ideas to use throughout the piece (development) that are based on the primary idea. A student takes their first product, the melody, and brainstorms through “how to develop”3 it through the five steps shown in Figures 24.2.

Assuming the student does the work, the next lesson is one of the most fun days the teacher will have teaching high school composers! They come in excited about what they have discovered: that they have control over what they are composing. They also lose the fear concerning finding new material. They begin to understand that composing is not mystical or based on luck, but is the result of hard work, craft, and editing. Three important things will now happen: 1) they will view their first draft more objectively, 2) they will come to you with ways to improve it, and 3) they will present their music and their ideas with greater confidence.

Skeletonizing shows students they can trust themselves. They will see that there are multiple solutions in most cases and that they are not stuck with their first (or only) idea. For a high school student to be able to discuss their work through the lens of what they changed as they edited their work is significant growth. They understand that they have control over their work and this reinforces the right kind of confidence in their artistic choices.

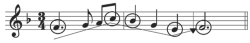

Step 1. Write out the melody by hand, then sketch out the basic shape of it. For example:

Step 2. Identify the crucial notes that make up the overall shape of the melody: if these notes were altered the melody would no longer be the basic shape, above.

Step 3. Remove all other notes and focus on the remaining notes which are the skeleton of the melody—the architecture holding it up. You can keep or strip the original rhythm. It helps to see the "pillars" of melody that hold up the overall shape.

Step 4. Using only the remaining notes from step three, try the following:

- Augment/diminish the rhythm, possibly to create a bass line or counterpoint.

- Invert them and repeat the first idea.

- Use them to create a new melody either in the basic shape or inverted.

- Try all the above in retrograde/retrograde inversion.

- Try various rhythms/dynamics/articulations/phrase markings, etc.

- Try various meter shifts, sequencing, location of weak/strong beat, tempo alterations, etc.

- Take the basic shape and stretch it out to four measures, eight measures-or make it shorter than the original.

- Try out a variety of textural ideas to go with the new ideas.

Step 5. Assignment. For our next lesson, create a full, handwritten page of musical ideas using any of these concepts.

Figure 24.2. Skeletonizing a melody

Date added: 2025-04-23; views: 187;