Some Common Challenges and Strengths of Student Composers

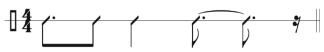

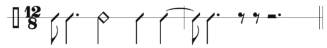

Challenges. One of the most common challenges that students need to address in preparation for advanced compositional study, as might occur within college composition programs, is that of notation. Software programs can make music sound great while simultaneously producing notation that is nearly unreadable by human performers. Figures 24.8 and 24.9 sound the same in computer playback, but Figure 24.9 correctly presents the rhythm in t while Figure 24.8 does not. Figures 24.10 (incorrect) and 24.11 (correct) highlight the same problem in compound meter.

DAWs and software notation programs are wonderful for many reasons, but students who begin their study using these programs need to also learn notational rules so that they can recognize errors that software can allow. I address this challenge by returning to physical notation with the following assignment: “Compose a one- to two-page piece for your own, unaccompanied instrument. Notate it by hand." If students have not yet learned to notate rhythms, this becomes a daunting task. Take time to show students how to physically notate their music by hand.

Figure 24.8. Incorrect version of written rhythm

Figure 24.9. Correct version of written rhythm

Figure 24.10. Incorrect version of written rhythm

Figure 24.11. Correct version of written rhythm

Another assignment that can help students recognize proper notation is to have them copy something small, perhaps a duet. Teach them to use a ruler to make bar lines, beams, and alignments of events like dynamics/lyrics/crescendo marks, etc. This process will slow them down so that they must observe all the details of the score they are copying. The resulting conversations that occur will help your students grasp rhythm (or other concepts) quickly and with greater depth of understanding.

Another common challenge is trust between student and teacher. Students want to trust their teacher, but if for some reason they do not give us that trust immediately, it can be earned by doing one thing: Talk less, listen more. Start by asking questions that encourage them to talk. For example, ask “What is the inspiration for your piece?" Most students want to talk for a while on this topic because they are excited to tell you all about it. Follow up with: “How did you make the harmony/rhythm/melody choices based on this inspiration?” Then listen. Most importantly, do not explain their piece to them. It is their art, their idea! The more you listen without interrupting the more you solidify their trust because you are interested in what they have to say as an artist. Hear who they are as an artist first, then work out the details of the problems. The rule of 5:1 applies (Benson, 2017; Zenger & Folkman, 2013). Speak five positives for every one (perceivable) negative. This will make the student willing to hear you. As more trust is earned, you can help them address more challenges in their music without their ego crumbling.

A third common challenge for students is recognizing that there are aspects of music often more important than the notes themselves. The musical gestures created by phrasing, dynamics, articulation, orchestration, etc. can have more power to create the desired musical result than choosing the exact right notes. A quick exercise I do with students to illustrate this idea is to have them draw their composition in shapes (gestures) with colored pencils. Questions that follow this exercise focus on why certain colors and shapes were chosen and lead to conversations that move beyond notes.

Strengths.A common strength is that students have limitless imagination and want to compose about every topic under the sun! They often do not have the musical language to achieve the sound they want or need, but that is part of this process. I sometimes have students literally bouncing up and down in my office, excited to tell me about their new idea. If imagination gets in the way of practicality, visit rehearsals, and let them see how performers work. How much time do percussionists need to change mallets? Why do the harpists not use their pinky fingers? How long will it take for the flute to switch to piccolo? How often do wind players need to breathe? Anything you can show rather than tell will preserve and inform their imaginations.

A second strength is that of collaboration. Students are excited to share their discipline with dance, theater, visual art, film, etc. If you can provide an opportunity for collaboration within your school community, do so! Work with students in-progress and do not wait for their piece to be finished. Review it at several stages as this will allow them to hear what is or is not working with ample time for change or revision. These changes and revisions are easier in progress because of two reasons: 1) it is easier for the student to make changes over smaller sections of their work than an entire piece; and 2) if they perceive it as complete, the problem of falling in love with their project returns. Once it is finished, read through it and give them a recording. If the work is strong enough, offer to put it on a concert.

The most important strength I have saved for last: determination. If a student wants to compose, they are going to compose, regardless of their skill level when they begin. As educators, it our privilege to nurture this potential and help it find direction. That direction, for some, may include composition study in higher education.

Date added: 2025-04-23; views: 225;