Creating the Environment. Developing Rhythmic Understanding and Readiness

Mistake-Safe Zone.Several factors are crucial in building an environment that is conducive to teaching composition. First and foremost, students must feel safe and comfortable while making music. If students regularly sing, chant, play, and move in their general music classes, they will have little problem doing the same things in an instrumental setting. This is by no means a new concept. Almost a century ago, music educators understood the importance of connecting new skills to the student’s established knowledge. Maddy and Giddings (1928) wrote:

Pupils learn to read vocal music by using the Do, Re, Mi syllables. Since they learn their songs by this method, does it not seem logical that they also use these syllables when they first enter the new realm of music represented by the instrument they wish to learn? There are enough necessary new details to bother them when changing from vocal to instrumental music, without having to learn a whole new vocabulary at the same time. (pp. 4-5)

If, however, students did not sing, chant, and move in classroom music, or if they are already developing or accomplished performers on their instrument, they may already have developed an assumption that band rehearsals do not include singing and chanting. In this case, as their teacher, we have another task to add to our “to do” list. Asking a student to sing musical ideas before performing them allows a teacher to understand whether the problem is conceptual (e.g., the student does not have an appropriate musical response) rather than technical (e.g., the student has a musical response but can’t yet perform that idea on their instrument). The former requires further teaching of the concept. The latter provides great intrinsic motivation for students to further develop their performance skills.

Developing Rhythmic Understanding and Readiness.Using the music learning/language learning analogy, our conversational vocabulary is more advanced than our written vocabulary. That is, students should be able to say (or sing/play) things that they cannot yet read or write (read/compose). A language teacher helps students learn proper usage and spelling to build vocabulary and written composition skills. Music teachers should simply do the same thing in music lesson and ensemble settings. The key is to teach what most people would call music theory in a non-theoretical manner. That is, we should name and explain things after a student develops an aural understanding. This requires us to regularly spiral back to help students connect concepts and deepen their understanding of music they can audiate and perform.

Rhythm and movement are inextricably linked. Encouraging students who struggle with rhythm to move and chant will help them feel pulse and subdivision. When chanting rhythms with students, I ask them to pulse macrobeats (i.e., the beat) in their heels, and microbeats (i.e., the subdivision) on their leg with fingertips. While some elementary students will manage this task with relative ease, I find that that some university music majors struggle with this task at first. This situation is actually quite normal. Gordon (1995) theorized that music aptitude, or potential to achieve in music, is normally distributed. Just like everyone has potential to achieve in language, all students have potential to achieve in music. Students with lower aptitude may simply require more support. Creative musical tasks allow students to work at an appropriate level of challenge.

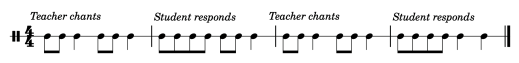

Figure 30.1. Chanting example #1

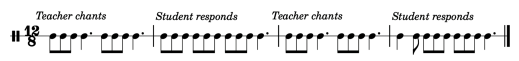

Figure 30.2. Chanting example #2

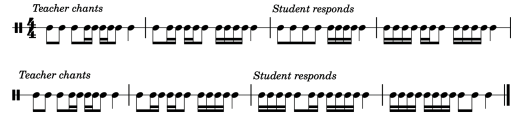

Figure 30.3. Chanting example #3

The goal of rhythmic readiness activities is to help students aurally create their own rhythms in a variety of meters and then to bring contextual meaning to them via use of a rhythmic system (e.g., 1-e-+-a, du-ta-de-ta, ta-ka-di-mi, etc.). Begin by chanting a one- or two-measure rhythm (see Figure 30.1) to the students and invite students to chant a response, in time, over the next measure(s). At this point, students should use a neutral syllable when chanting. After repeating the process several times, ask several students to share their responses.

The rhythmic context should reflect the literature they are currently learning to perform. Difficulty should be based on students’ musical abilities. If they have greater rhythmic facility, you could use more challenging antecedent phrases. For example, Figure 30.2 may be appropriate for beginner level student musicians while Figure 30.3 would likely be more appropriate for more advanced students as the rhythms are more complex and the phrases are two measures long.

After the students have improvised consequent phrases, the teacher may need to help them write the phrases they improvised. This is done by bringing rhythmic context to the improvised rhythm using syllables from the chosen rhythm system. It is important that the musical sound comes before the process of writing. We would not admonish a four-year-old not to say words that he cannot spell. Likewise, we should not constrain his musical development to rhythms that he can write. The drive to read and write what one can speak is an important factor in the intrinsic motivation to improve reading and writing skills.

Date added: 2025-04-23; views: 227;