Improvisation as an Instructional Tool

Improvised endings are a beneficial activity for students to grow their creative skills and a gateway to composition. While this section is focused primarily on readiness activities, invented endings are great beginning composition exercises. Sarath (1996) delineated between composition and improvisation, stating improvisation is the “spontaneous creation and performance of musical materials” (p. 3) while composition is a process that allows for reflection and revision.

In a study involving non-notated composition, Kratus (1989) differentiated between improvisation and composition by asking a student to repeat their musical creation, defining composition as “a unique, replicable sequence of pitches and durations” (p. 8). If a student “finalizes” a response in an invented endings activity, even if it only an aural response, it should be considered a composition.

As you can see from the relative lengths of the descriptions in the previous section, developing melodic and harmonic understanding is much more time consuming than developing basic rhythmic understanding. This should not preclude you from asking students to sing invented endings to melodies before you have “thoroughly covered the topic.” Remember that musical abilities vary widely. Some students will show great success with relatively little input from their music teacher while others may struggle even after several years of music class. Student responses to creative tasks help us to understand individual differences and adapt our instruction to help each student to more meaningful levels of creativity.

Whole-class improvised ending activities are useful for giving each student a mistake-safe zone to explore musical possibilities. I would encourage you, however, to listen to some individual responses, even if you only ask for volunteers at first. You may continuously sing the antecedent phrase for any students who indicate that they have an ending they want to share. Perhaps you could have the whole class repeat student responses. Success at simple tasks will build confidence and a greater willingness to take musical chances. As students become more comfortable with this process, feel free to add constraints to the challenge (e.g., you must end on do, you can’t begin on mi, reuse a rhythm from the first phrase). The goal is to grow students’ audiation and instinctual response to musical settings. Just keep the challenge appropriate to students’ skill levels. Something as simple as an improvised two- or four-measure response may provide insight into a student’s depth of understanding. Consider the examples in Figure 30.9.

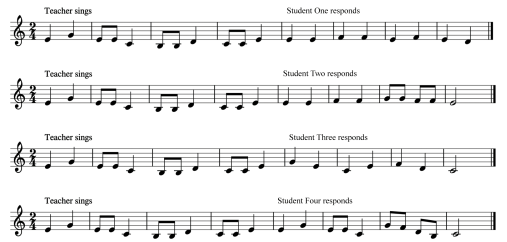

Figure 30.9. Examples of student-invented endings

This antecedent phrase was written to be used with “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” “London Bridge Is Falling Down,” and “Go Tell Aunt Rhody.” It consists of simple rhythms and uses the same harmonic pattern. All four student responses demonstrate rhythmic understanding. They are eight beats long and use similar rhythmic patterns. Student One sings a response that does not reuse the harmony from the model songs or the antecedent phrase. The other three responses all fit the harmonic structure of the given melodies. Student Two uses greater rhythmic variety but a more limited palette of pitches while Student Three uses only macrobeats but a wider range of pitches.

Student Four sings a melody that reuses the first half of the antecedent phrase and then outlines the dominant chord to end on do. While Response One doesn’t fit the harmonic structure, it is not incorrect. It simply indicates that the student may not infer the same harmony or that they need more time and experience to develop their harmonic understanding. Responses Two and Three may indicate greater harmonic understanding. Response Four is least likely to be an accidental indicator as it demonstrates both a reuse of the source material and a more thorough harmonic understanding. I would encourage you, as the teacher, to take a moment to highlight the techniques that make Response Four exemplary, or, better yet, ask the students to point out these things.

Date added: 2025-04-23; views: 200;