Developing Melodic and Harmonic Understanding and Readiness

Melodic readiness activities allow students an opportunity to develop an understanding of how melodies are constructed. Harmonic readiness activities help students understand harmony in both a vertical and linear manner. This understanding will inform the construction of their own melodies as well as the harmonization of pre-existing melodies.

As with the rhythmic readiness activities, the goal is to bring contextual understanding to familiar materials that have been learned aurally. Context is brought to melodic material via a tonal system. I use moveable-do solfege with Za-based minor to discuss and analyze all tonal examples and rhythm syllables developed by James Froseth (sometimes referred to as “the Gordon System”) to discuss and analyze all rhythmic examples. I have colleagues who prefer various tonal and rhythm systems including do-based minor or numbers for tonal analysis and performance, and “Takadimi” or “i-e-and-a” for rhythm. I don’t mean to diminish the efficacy of other systems. Each teacher should feel free to choose the tools they find most effective for bringing contextual meaning to music.

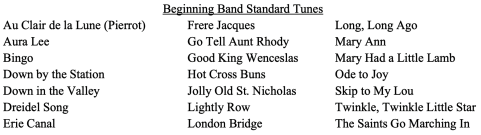

Jazz musicians learn standard tunes to develop their skills. Kodaly suggested that students begin music learning with folk songs from their native land. Band music also has standard tunes (see Figure 30.4) for a list of tunes produced by a brief search of five different beginning band books).

Figure 30.4. Beginning band standard tunes

Every one of these songs is worthy of study for melodic and harmonic structure. They are gems that have each stood the test of time—at least 75 years. Similar literature lists can be compiled for more advanced ensembles based on the most common and familiar literature.

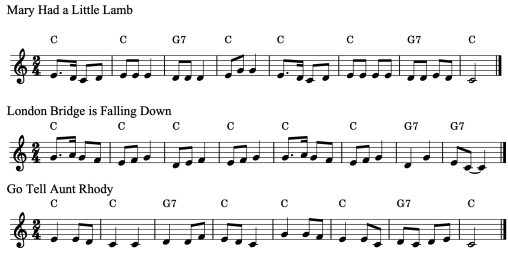

Azzara (2015) lists four skills essential to developing comprehension. Students must learn to (a) group pitches into meaningful patterns and phrases, (b) compare patterns, phrases, and tunes, (c) interact when performing, and (d) anticipate and predict patterns and phrases. To exemplify these skills we will examine three of the tunes from Figure 30.4 (see Figure 30.5).

Figure 30.5. Three example tunes

Sing through the tunes, one at a time. Focus on the rhythmic aspect of each tune. Are there meaningful patterns that are repeated? Do the phrases have similarities? Does the tune have a sense of unity? Does it have a sense of variety? After performing the first and second tunes, did you notice any similarities between “Mary Had a Little Lamb” and “London Bridge?” After singing and thinking about the first two tunes, were you making any predictions about “Go Tell Aunt Rhody?” Did you find more similarities? Did you find any differences? Take a few moments and repeat this process, focusing on the melodies, and answering the same questions. Finally, repeat the process a third time, focusing on the harmonic structure of each.

Now that you have had an opportunity to sing the songs several times and ask yourself those questions, let’s see if we noticed the same things. There is considerable reuse of rhythmic material in “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” Measure 5 is an exact rhythmic repeat of measure 1. Measures 2, 3, and 4 are rhythmically the same, as are measures 6 and 7. As we look at “London Bridge,” measures 1 and 5 are the same as are measures 2, 3, 4, and 6. In fact, the first six measures of both songs are rhythmically identical. “Go Tell Aunt Rhody,” while not using the same rhythms, does have significant reuse of rhythmic material. Measures 1, 3, 5, and 6 are all the same rhythm and measure four is a mirror image of that rhythm. Zooming out from patterns to phrases, each tune repeats the first half of the antecedent rhythmic phrase, varying only the last two measures. Generalizing from our answers to these questions helps us to understand that at least some well-written songs reuse rhythmic material but not in strict imitation. This is one way that a composer balances unity and variety in a composition.

When examining the pieces tonally, we find that melodic material is reused in much the same fashion as rhythmic material. Each melody moves primarily by step with occasional skips. Each melody is entirely diatonic. Harmonically, all three pieces use the same two chords, tonic and dominant. In fact, they all follow the same harmonic progression. With only one exception, each melody features a chord tone on every beat of every measure.

Now that you have taken a more in-depth look into the construction of these three well-worn tunes, do you have some new ideas you could use when composing your own tunes? Have you ever thought about the construction of a simple song in this manner? I certainly hadn’t when I was a young teacher. My experience had exclusively been unidirectional. Someone presented me with notation, and I tried to re-create that notation correctly, use correct fingerings, play the right rhythms. My performance lacked comprehension because I was too focused on musical minutiae to look for patterns. To draw further parallels with our language/music analogy, individual notes are like individual letters. We don’t spell when we read or speak, we group letters into meaningful chunks.

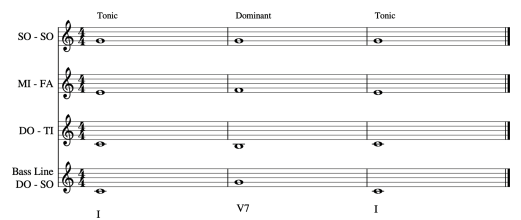

With practice, our ability to decode notation and re-create notated music improves. Sadly, many wind players rarely develop an understanding of functional harmony because they play instruments that can produce only one note at a time. To develop harmonic understanding, Grunow, Azzara, and Gordon (2020) use tonal patterns (see Figure 30.6) that outline harmony for a given piece of music.

Figure 30.6. Tonal patterns

The examples above are all based on tonic and dominant harmony. This is a good place to begin as it presents students with an either/or choice. All the patterns are either tonic patterns (any combination of do, mi, and so), or dominant patterns (any combination of so, ti, re, and/fa). Like the rhythmic readiness activities, these are sung by the teacher and imitated by the students using a neutral syllable first. Initially, the patterns are presented in the same order, so they become predictable. Gradually the teacher introduces solfege to the patterns. As students learn to identify the patterns as tonic or dominant, the order is changed. As harmonic understanding deepens, students may improvise their own tonic and dominant patterns.

The second step to building harmonic readiness is helping students apply their developing understanding of chords to the harmonic structure of a given piece of music.

Azzara and Grunow (2006) developed a process for students to sing, play, and understand harmony in a linear manner. After learning the melody of a song, students are taught to sing and play a bass line by improvising rhythms on the roots of the chords (see Figure 30.7).

Figure 30.7. “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” melody and bass line

Once the student learns the bass line, inner voice lines may be added using the following voicings (see Figure 30.8).

Figure 30.8. Simple linear harmone

These harmony parts are similar to guide tone lines used by jazz musicians. That is, they provide a linear pathway that helps the performer move as little as possible while navigating the harmony of the piece. As with all the prior steps, this task should be learned aurally.

As students become more comfortable with tonic and dominant chords, the same process can be repeated with new tunes to expand students’ knowledge and skills. Choices in literature should include tunes in major and minor keys, with tonic, dominant, and subdominant harmony. Modal tunes also work well as students will find connections to contemporary band literature and classic rock songs, many of which are in Mixolydian and Dorian modes. There are a number of online resources and crowdsourced lists of popular music written in various modes. This process is a powerful teaching tool as it is adaptable to any piece of music.

Date added: 2025-04-23; views: 217;