Composition Activities and Assignments

The following activities are examples of composition assignments I have used or observed other teachers using with students at all levels of instruction. The literature that students are learning and performing, whether that be tunes from a method book or published literature for their ensembles, represent the best source materials for these activities.

The goal is to help the students be creative with the knowledge and skills that they have mastered. Some of these activities will be easy to use immediately, others will require time for students to build greater content knowledge and skills. The five activities presented below begin with basic rhythm composition before adding harmonic and melodic elements. They are generally presented in increasing level of difficulty although each activity can be adapted to make it easier or more challenging. Student work is included for most activities to provide insight into what may be possible if we help our students find and develop their creative musical voice.

Composing Rhythmic Warm-Up Activities.An excellent first step for beginning composers is creating rhythmic warm-up activities for their ensemble. There is no time constraint or concern over whether a piece can be effectively programmed. Furthermore, students can be creative rhythmically regardless of their level of tonal understanding. They can be encouraged to find challenging rhythms from their performance literature and write exercises that will help the ensemble read, understand, and perform those rhythms (and others that may be similar). Students with more developed rhythmic skills may compose longer rhythmic phrases or rhythm duets, focusing on reuse and interaction of rhythmic material.

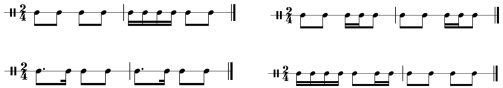

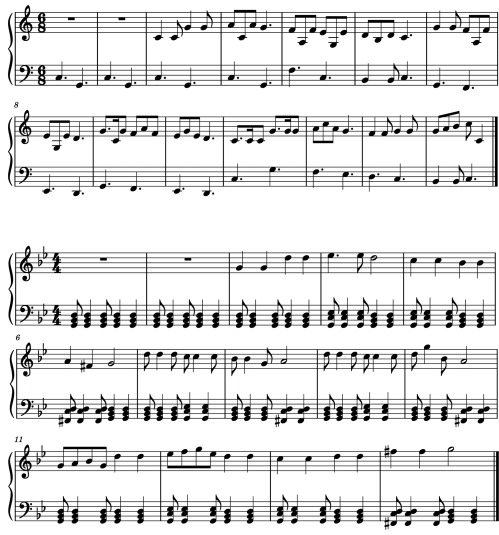

Assembling a Rhythmic Trio.Merriam-Webster (n.d.) defines composition as “arrangement into specific proportion or relation and especially into artistic form.” Here is a simple composition activity based on Holst’s First Suite in £"(1984) that can be easily scaled up from a handful of two- measure rhythms to a much larger rhythm ensemble piece. To provide greater connection to the literature they are performing, students extracted rhythms from the third movement. Four rhythms that students extracted are in Figure 30.10.

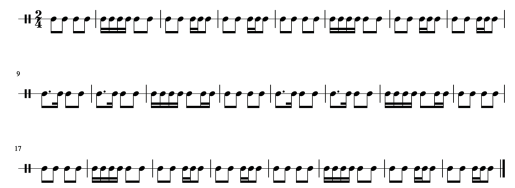

The teacher helped students assemble their patterns into a question/answer format which, when repeated formed an eight-measure phrase. Two phrases were assembled into a larger ABA rhythm composition. Figure 30.11 is the assembled 24-measure ABA composition.

Figure 30.10. Students’ extracted rhythms

Figure 30.11. Assembled ABA composition

Figure 30.12. Assembled ABA rhythm trio

After assembling the rhythmic composition, students then completed a group analysis of rhythms Holst used to help them plan a “motor” to accompany their composition. An example of a student group’s ABA rhythm composition is in Figure 30.12.

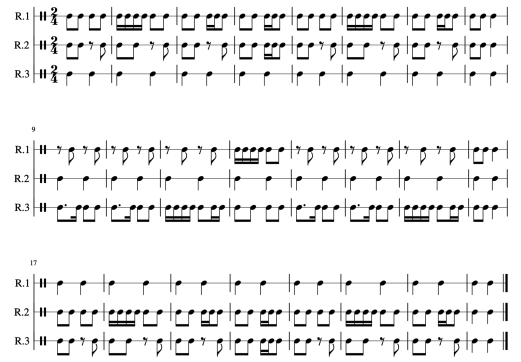

Harmonizing a Scale/Warm-up Chorale.As students develop their harmonic understanding, harmonizing a scale with limited choices for what harmonies to include can help them to understand the process of harmonizing pre-composed melodies. Students can harmonize a scale using only primary (I, IV, V7) chords (See Figure 30.13 for an example). Familiarity with primary chords can be developed by having students sing and identify tonal patterns that include pitches from tonic, subdominant, and dominant chords (see Figure 30.7). Using the scale as a melody, students can choose appropriate I, IV, and V7 chords that fit with the given scale pitches and write harmony lines that will outline the primary chords of the given key.

Figure 30.13. Harmonized scale I, IV, V

After students develop some facility with the process, they can harmonize simple melodies as warm-up chorales. Begin with short phrases and make sure that the source material is appropriate for the harmony they can use (e.g., do not give the students a phrase that has accidentals or modulates to a new key.) This process will be more effective if you provide the students with examples of four-part chorales they can read and perform. After they can sing, play, and aurally recognize how phrases end, you can name those given cadences (e.g., authentic cadence or plagal cadence.) As your students’ understanding of harmony grows, so can their palate for harmonizing scales and melodies. Just remember to always start with an aural idea, help the students to understand it contextually, and then name it and discuss music theory.

Composing Variations on a Theme.When students compose variations on a theme, they are demonstrating higher order musical thought. Playing a melody is a relatively simple task. Changing the melody from one meter to another or one key or mode to another demonstrates the ability to conceive of source material through various musical lenses. Composing variations also allows for greater differentiation as students can engage with the musical material at whatever level their skills will allow. For students who haven’t written variations before, teachers may introduce the concept by playing a recording of variations on simple themes such as Mozart’s Variations on “Ah vous dirais-je maman” for piano or Alfred Reed’s Variations on LBIFD (“London Bridge is Falling Down”) for brass quintet. These are particularly useful because the source material is so familiar. More advanced examples might include John Barnes Chance’s Variations on a Korean Folk Song or James Barnes’ Fantasy Variations on a Theme by Niccolo Paganini, as the theme is plainly apparent through most of the variations in both pieces.

This kind of activity works well in warm-up routines. After playing a scale and a tune in the same key, the teacher, or a chosen student, plays a variation on the tune. After each variation, a member of the class describes the variation (“He changed the meter to 6\8 ” or “She played the tune in Lydian”). In addition to allowing each student the opportunity to compose, adding descriptions provides a platform for students to build contextual knowledge. The activity can culminate with everyone attempting to play the variation by ear.

One of the keys to engaging students in composition is performing student work (Doiron, 2019). Using student composed variations in a “Theme and Variations on ” is an excellent way to include many student compositions in a concert. Initially, the teacher may need to arrange the theme and assemble the variations although the students will undertake this task as well once they have a good model for doing so. Figures 30.14 has examples collected from students who were writing variations on “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” using Charles Ives Variations on America (1949) as a model. The first variation set the melody in 6\8 time and ornamented it with large skips while the second featured the melody set as a dance in a minor key. Figure 30.15 is an interlude written in two keys (Bb major and G major) and separated by two beats that eventually resolves into G minor. The student who wrote this was exceptionally proud of it as the Ives example also featured an interlude with the melody in canon written in F major and Db major at the same time.

Figure 30.14. “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” variations

Figure 30.15. “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” interlude

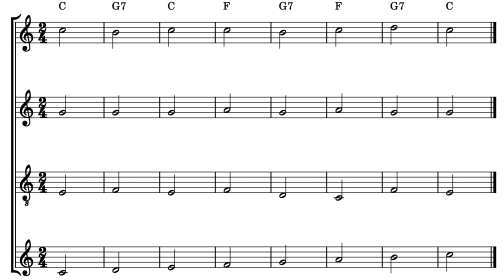

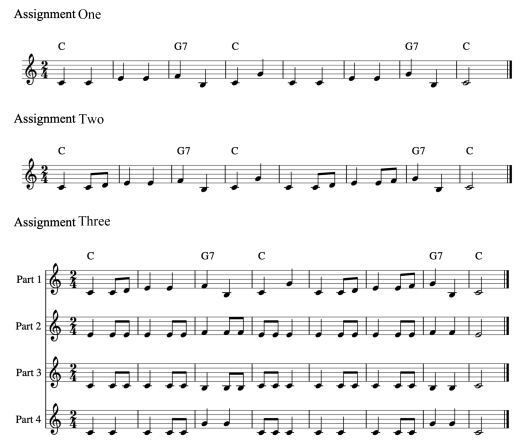

Composing a Basic Contrafact.A contrafact is a musical composition based on the harmonic structure of an existing piece of music. Many jazz greats have written new melodies based on the chord progression of a tune from their standard repertoire. As we discussed above, elementary musicians also have a standard repertoire, one that provides the same opportunity to improvise and compose upon. I break this task into several parts to enable feedback and revision. The three composition tasks are provided in Figure 30.16. Figure 30.17 shows one fifth-grade student’s composition as it evolves through the various stages.

The first assignment only allows chord tones so the teacher can check for harmonic understanding (i.e., does the student know what notes fit the given chord?). The second assignment allows the student to add non-harmonic tones to the melody. Assignments

Contrafact Assignment #1. Using the chord progression from the model song, write the bass line on the bottom staff and your own melody on the top staff.

- Use one rhythm with a little variation at the end.

- Use only chord tones.

- End on do.

Contrafact Assignment #2. Using the chord progression from the model song, write the bass line on the bottom staff and your own melody on the top staff.

- You may use chord tones, passing tones, and neighboring tones.

- Use one rhythm with a little variation at the end.

- End on do.

Contrafact Assignment #3. On a new piece of staff paper, use your composition from assignment two and compose a quartet by writing two inner voices.

- Be as lazy as you can with the inner voices, (do-ti-do) (mi-fa-mi)

- Choose a rhythm pattern that complements your melody and use that for BOTH inner voices.

Figure 30.16. Three-part contrafact composition assignment

Figure 30.17. Fifth-grade student composition

One and Two may be combined if a student already has a melody that includes passing or neighboring tones. They have been separated in this case to help students who may need a more step-by-step process. The third assignment uses the linear harmony from Azzara and Grunow (2006).

The completed four-part arrangement above would be a great addition to a performance. Having students compose and arrange duets, trios, and quartets allows them the added responsibility of chamber playing. Parts can easily be adjusted or transposed for other instruments. If the bass line is too easy, encourage the students to alternate between the root and fifth of each chord. If the inner voice parts seem boring, add the rhythm from the horn part of a march. A student could write a similar melodic part (a harmony line) or a second part that was rhythmically and melod- ically simpler and the two melodies could work as a partner song.

These tasks provide an opportunity to discuss harmony, parallel motion, complete voicing of triads, or any number of other pertinent topics because they are no longer theoretical. That is, the students are using all this information to adapt their own musical creation. The possibilities are only limited by the boundaries of the songs that the students know and can audiate.

Date added: 2025-04-23; views: 203;