Deforestation and Climate - Some Early Views

The notion that vegetation affects climate is not new. Over two thousand years ago, Theophrastus wrote that draining marshes removed the moderating effect of water and created a colder climate, while deforestation exposed the ground to the Sun and warmed climate (Glacken 1967, p. 130; Neumann 1985). The concept that forests increase rainfall can be traced back to the Roman natural philosopher Pliny the Elder and his Natural History) written in the first century AD (Andreassian 2004).

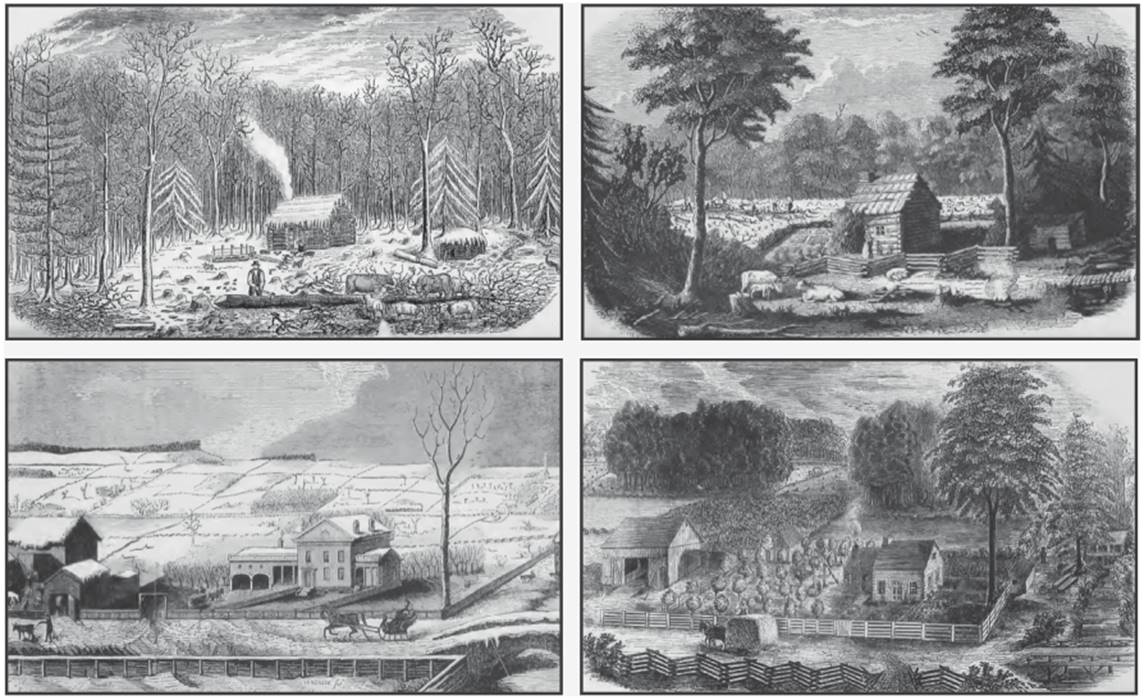

European naturalists in the seventeenth and eighteen centuries, too, believed that the wide-ranging clearing of forests and cultivation of land in Europe had moderated the climate since antiquity (Fleming 1998). Settlers of the New World carried with them a similar sentiment, and a vigorous debate arose about whether the extensive land clearing (Figure 1.2) was indeed changing the climate of America (Thompson 1980) Fleming 1998). Like debates arose in Australia, where much of the native forest and woodland was cleared following British settlement, and similarly with British colonization of India.

Fig. 1.2. Sketches of land clearing in western new york (clockwise from top left). in the fi rst panel, the initial forest clearing is small, only to fell trees for the small log house and to raise a few livestock. the second panel shows the settler has cleared a few acres of land. ten years have passed in the third panel. thirty to forty acres of land have been cleared, and neighbors have

cleared their land. the fi nal panel depicts 45 years following the initial clearing. from turner (1849, pp. 562–566)

One question concerned whether deforestation and cultivation of land created milder winters. A popular view, espoused by the Scottish philosopher David Hume, was that deforestation opened the land to heating by the Sun during winter. In an essay (ca. 1750) he explained that warmer winters occurred because “the land is at present much better cultivated, and that the woods are cleared, which formerly threw a shade upon the earth, and kept the rays of the sun from penetrating to it” (Hume and Miller 1987, p. 451). Because of this, Hume declared that “our northern colonies in America become more temperate, in proportion as the woods are felled.” Similar views are seen in the writings of the New England Puritan minister Cotton Mather, who observed that “our cold is much moderated since the opening and clearing of our woods” (Mather 1721, p. 74). Benjamin Franklin, too, believed that climate was warming because “when a country is clear’d of woods, the sun acts more strongly on the face of the earth” (Franklin and Labaree 1966). Franklin’s contemporary Hugh Williamson, a physician, scholar, and politician, predicted that with continued clearing of interior lands “we shall seldom be visited by frosts or snows, but may enjoy such a temperature in the midst ofwinter, as shall hardly destroy the most tender plants” (Williamson 1771). Thomas Jefferson agreed that “a change in our climate . . . is taking place very sensibly” (Jefferson 1788, p. 88) and urged climate surveys “to show the effect of clearing and culture towards changes of climate” (Jefferson and Bergh 1905). Samuel Williams, a Congregational minister, professor at Harvard, and founder of the University of Vermont, believed that as trees were cut down and settlements increased “the cold decreases, the earth and air become more warm; and the whole temperature of the climate, becomes more equal, uniform and moderate” (Williams 1794, p. 57). This climate change “is so rapid and constant, that it is the subject of common observation and experience.”

Not all agreed with this sentiment. In addition to being a lexicographer, Noah Webster of Connecticut was a political writer. He strongly refuted the notion of such changes in climate in an essay published in 1799. Direct observations of climate change were lacking, he noted, and evidence of a warmer climate relied on anecdotes and personal memories. Yet, he, too, admitted to differences between forests and cleared land that altered local climate (Webster 1843, pp. 145). “While a country is covered with trees,” he wrote, “the face of the earth is never swept by violent winds; the temperature of the air is more uniform, than in an open country; the earth is never frozen in winter, nor scorched with heat in summer.”

The writings of Europeans attested to the prominence of the forest-climate debate, and also to the difference in opinions. Constantin- Francois Volney published a book in 1803 based on his travels in eastern North America. He observed that “for some years it has been a general remark in the United States, that very perceptible partial changes in the climate took place, which displayed themselves in proportion as the land was cleared” (Volney 1804, p. 266). Alexander von Humboldt responded in 1807 that “the statements so frequently advanced, although unsupported by measurements, that since the first European settlements in New England, Pennsylvania, and Virginia, the destruction of many forests . . . has rendered the climate more equable, - making the winters milder and the summers cooler, - are now generally discredited” (Humboldt et al. 1850, p. 103). The Edinburgh Encyclopaedia asserted that the theory of land-use climate change “is, we fear, to be regarded rather as the birth of a lively fancy, than the offspring of accurate science” (Brewster 1830, pp. 613-614).

Another belief was that forests contributed to the plentiful rainfall in America and that deforestation decreased rainfall. Christopher Columbus developed such a view from his travels to the New World. His son wrote in a biography that he attributed the rainstorms of Jamaica to “the great forests of that land; he knew from experience that formerly this also occurred in the Canary, Madeira, and Azore Islands, but since the removal of forests that once covered those islands, they do not have so much mist and rain as before” (Colon and Keen 1959, pp. 142-143).

Natural scientists developed similar views. John Evelyn declared in 1664 that forests “render those countries and places more subject to rain and mists” (Evelyn 1801, pp. 29-32). John Clayton, an English naturalist and clergyman, attributed the violent thunderstorms of coastal Virginia to the dense forests (Clayton 1693; Berkeley and Berkeley 1965, pp. 48-49). His compatriot John Woodward described how the “great moisture in the air, was a mighty inconvenience and annoyance to those who first settled in America,” but that after clearing the forests “the air mended and cleared up apace: changing into a temper much more dry and serene than before” (Woodward 1699). Samuel Williams accounted for the plentiful rainfall because “the immense forests . . . supply a larger quantity of water for the formation of clouds, than the more cultivated countries of Europe” (Williams 1794, p. 50). Hugh Williamson described a feedback by which forest evaporation enhances rainfall and cools climate (Williamson 1811, pp. 23-25): “The vapours that arise from forests, are soon converted into rain, and that rain becomes the subject of future evaporation, by which the earth is further cooled.” In the Caribbean islands, which had undergone widespread forest clearing to grow sugar cane, forest preserves were created to promote rainfall (Anthes 1984).

Settlement of the Great Plains in the 1870s and 1880s shifted the debate from deforestation to afforestation, with the premise that tree planting would increase rainfall (Emmons 1971; Kutzleb 1971; Thompson 1980; Williams 1989). An official in the United States Department of Interior claimed that “the planting of ten or fifteen acres of forest trees on each quarter section [160 acres] will have a most important effect on the climate, equalizing and increasing the moisture” (United States General Land Office 1867, p. 135). That some official believed that “if one-third the surface of the great plains were covered with forest there is every reason to believe the climate would be greatly improved” (United States General Land Office 1868, p. 197). Congress agreed and enacted the Timber Culture Act of 1873 to promote afforestation. Popular science gazettes, too, advocated tree planting to increase rainfall (Oswald 1877; Anonymous 1879). Samuel Aughey, of the University of Nebraska, promoted the notion that plowing the prairie sod was the cause of an increase in rainfall observed at that time. Cultivation allowed the soil to retain more rainfall, which evaporated and rained back onto the land, he theorized (Aughey 1880, pp. 44-45). Charles Wilber popularized this notion with the phrase “rain follows the plow” (Wilber 1881, p. 68). He described how an “army of frontier farmers . . . could, acting in concert, turn over the prairie sod, and . . . present a new surface of green, growing crops instead of the dry, hard- baked earth covered with sparse buffalo grass. No one can question or doubt the inevitable effect of this cool condensing surface upon the moisture in the atmosphere.”

A sharply divided debate on forest-climate influences continued in the latter half of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth century. Conservationists, botanists, and foresters argued for such influences. George Perkins Marsh devoted a large portion of his treatise Man and Nature to forest-climate influences (Marsh 1864). The botanist Richard Upton Piper agreed that “forests trees should be preserved for their beneficial influence upon the climate” (Piper 1855, p. 51). The fledgling forestry division of the United States Department of Agriculture issued reports supportive of the burgeoning field of forest meteorology and forest-rainfall influences (Hough 1878; Fernow 1902; Zon 1927).

Climatologists of the day, however, dismissed the study of forests and climate. A publication on the climate of the United States asserted that “the great differences of surface character which belong to the deserts, woodlands, and other more striking features, are believed to have their origin in climate, and not to be agents of causation themselves” (Blodget 1857, p. 482). The geographer Henry Gannett suggested that faulty reasoning was behind the belief that forests increase rainfall. His analysis of precipitation records found no change in rainfall in regions that had undergone increases and decreases in tree cover, and he complained that “a satisfactory explanation of this supposed phenomenon has never . . . been offered” (Gannett 1888). He further explained that “it may be that in this case an effect has been mistaken for a cause, or rather, since it is universally recognized that rainfall produces forests, the converse has been incorrectly assumed to be also true” (Anonymous 1888). The eminent meteorologist William Ferrel argued in favor of large-scale control of precipitation by atmospheric circulation, not by surface conditions (Ferrel 1889). His colleague Cleveland Abbe wrote that “rational climatology gives no basis for the much-talked-of influence upon the climate of a country produced by the growth or destruction of forests . . . and the cultivation of crops over a wide extent of prairie” (Abbe 1889). Abbe believed that “the idea that forests either increase or diminish the quantity of rain that falls from the clouds is not worthy to be entertained by rational, intelligent men” (Moore 1910, p. 7).

Foresters and climatologists in the United States Department of Agriculture were sharply divided over forest influences on rainfall. While the foresters issued reports in support of the science (Hough 1878; Fernow 1902; Zon 1927), their colleagues in the department’s Weather Bureau (the predecessor of the present-day National Weather Service) resoundingly dismissed these ideas. Mark Harrington, chief of the Weather Bureau, rejected his forestry colleagues’ belief that forests affected climate in any manner (Fernow 1902). Willis Moore, Harrington’s successor, also rebuffed studies relating forests and climate with the retort that “while much has been written on this subject, but little of it has emanated from meteorologists” (Moore 1910, p. 3). “Precipitation,” he explained, “controls forestation, but forestation has little or no effect upon precipitation” (Moore 1910, p. 37). The caustic rhetoric confused a writer in the journal Nature, who reported that “the literature on the subject is somewhat bewildering” (Anonymous 1912).

The views about ongoing climate change in colonial America ultimately proved to be false. Climate was not changing; winters were not becoming milder with land clearing; rainfall was not decreasing because of deforestation or increasing because of tree planting and soil cultivation. However, meteorologists of that era, too, were ultimately proved wrong. As they sought physical explanations for geographic variations in climate, they were too quick to dismiss the precept that forests, grasslands, croplands, and other ecosystems do indeed influence climate. Interest in the climatic effects of deforestation, cultivation, and overgrazing reemerged in the 1970s, with recognition that human activities do indeed change climate and that land use is one such mechanism for climate change (Landsberg 1970; Otterman 1974, 1977; Schneider and Dickinson 1974; Sagan et al. 1979). One hundred years after a writer to Nature found the debate to be “belwidering,” the journal published another paper that found that tropical forests do indeed increase rainfall (Spracklen et al. 2012).

Date added: 2025-05-15; views: 275;