Villa Gamberaia. History of Creation

Villa Gamberaia. History of Creation. To the east of Florence is the war-ravaged shell of a beautiful country villa, Gamberaia, built in 1610 by Gamberelli for the Dukej of Zenobi Lapi, and, until recently, considered one of the most perfect in all Italy. Yet when it was planned many said that the city was in all ways impossible and that the villa should never be built. In many ways these critics were right, for most of the natural and manmade elements of the landscape seemed detrimental. The property was unusually small.

It was split by a busy trade road with its attending confusion and dust. The property to the north of the road was steep and rocky. The buildable area had only a passable view to the south, and the major view, to Florence and the cathedral, lay to the west — into the hot, cruel, slanting rays of the evening sun.

But for reasons that would seem all too familiar to the planner of today, the Duke was determined to build there. As he forcibly declared :

- He already owned the property.

- It had belonged to his family and had sentimental value.

- There were few better citys available, and they were frightfully expensive.

- On the other hand, if he didn’t use this property, who knows when he could sell it.

- Besides, he wanted his villa right here.

- Time was of the essence. He must waste no more time in hunting a better city. He must get this program rolling.

- He had engaged a good architect to build it here, and if this architect couldn’t do it, the Duke would find another one who could.

One can imagine Gamberelli roaming the city, noting each facet of the landscape, carefully observing each tree, each rocky outcrop, each varying sector of the view. At last he felt confident that the unfortunate features of the city could be minimized by skillful handling and that the commendable features of the city could be accentuated to create a delightful villa.

After all, the passing road did provide good access to Florence; there was a view of the city; the land did slope generally to the south for warmth in the early spring and late fall. The northern cliff, although craggy, was covered with gnarled and picturesque trees. Best of all, a mountain stream could be tapped to provide a flow of that most essential element, clear, cool water. Gamberelli set to work.

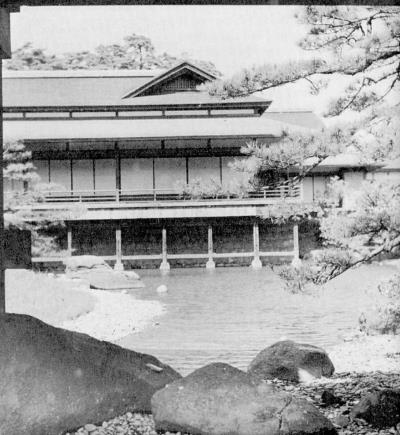

The Rinshun Pavilion: in the Japanese tradition of planning, the builder first of all determines the highest qualities of a city and so builds as to accentuate these qualities, rather than destroy them

To connect the divided property and to provide a point of high interest at the road, he constructed across it a great walled ramp supported by a wide, deep arch through which traffic could pass. Near its base he fashioned a fountain basin where travellers could pause and be .refreshed. In the shaded court thus formed by the walls and steep road shoulders he set the entrance gate that would lead to the house and gardens. The residence he fitted to the solid rocky contours of the slope, raising it above the entrance gate for privacy and a command of the best exposures.

Southward from the structure he leveled a garden panel, which terminated at an arched wall of clipped trees. The wall of trees effectively screened all but a selected arc of the southerly view, and this sector of view was brought into sharp focus and modulated into a rich montage by the dark green arches of architecturally treated foliage.

To the east, and parallel with this panel, Gamberelli developed a long axis through the tangled trees and across the road by a ramp, to sculpture and a quiet pool set amidst tall cypress trees at the extreme limit of the Duke’s land. This long axial vista not only completed the unification of the split property but gave a pleasant impression of great distance and expansive freedom within the limited property confines. Moreover, the rigidly towering cypress and the narrow vista thus created accentuated, by telling contrast, not only the wild but also the precipitous natural character of the city.

While the western view was unpleasant in late afternoon, Gamberelli must have reasoned, it was most pleasant for the rest of the day. This view was screened from the other garden areas, but from the west terrace it was displayed in full sweep. In the evening, after the sun had dropped behind the horizon, the western sky, ablaze with high color or muted in pastel twilight, served as a backdrop to Florence and her bridges, domes, and spires; then, from the terraced gardens of Gamberaia, with their splashing fountains and scent of boxwood and lemon trees, the view was of such haunting beauty that it could not soon fade from the memory of those who saw it.

The changing landscape. The most constant quality of the manmade landscape is the quality of change. Man is forever tugging and hauling at the land. Sometimes senselessly — destroying the good features of the land as he found it. Sometimes intelligently — developing a union of function and city with such sensitivity as to create a landscape improvement, as at Villa Gamberaia. Each time man-made elements, tangible or intangible, are imposed, wisely or unwisely, on a land area, it must be reconsidered by the planner in the light of its revised landscape character.

The physical planning of any land area is a continuing process. It is forever seeking the best expression of that function or complex of functions (present or anticipated) best adapted to the natural and man-made elements of the environs.

Date added: 2025-08-01; views: 156;