Spatial Size. Spatial Form

Spatial size. Planned spaces are usually considered only in relation to man or the functions of man. Paddocks, corrals, dog-runs, canary cages, and elephant traps are exceptions, but even these spaces are best conceived with more than fleeting attention to the habits, responses, and requirements of the proposed occupants. Take the elephant trap, for instance. Few architects approach their planning with a keener awareness of their client’s traits and habits than the native builder who directs the construction of the stout tirrfber and rattan enclosure for the trapping and training of wild elephants.

The canary cage too, with its light enframement, seed cups, swinging perches, and cuttlebone, is a volume contrived with much thought for the well-being of the canary. In planning spaces for man, it seems plausible that his accommodation and happiness should be of equal concern to the planner as are those of the bird and the pachyderm.

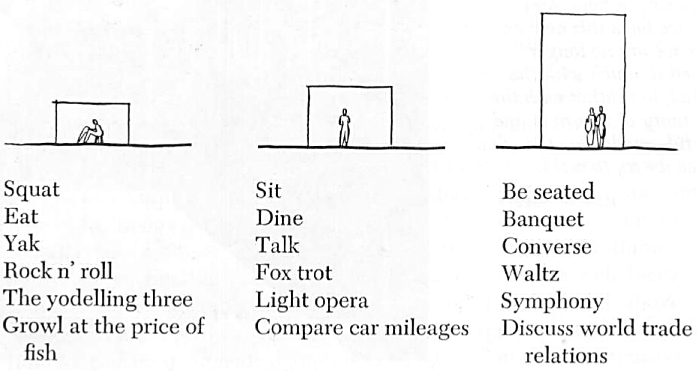

It is well known that the size of an interior space in relation to man has a strong psychological effect on his feelings and behavior. This fact may be illustrated graphically as follows:

Exterior spaces have similar psychological attributes. On an open plain a timid man feels overwhelmed, lonesome and unprotected; left to his own devices, he soon takes off in the direction of shelter or kindred souls. Yet, on this same plain, the bolder spirit feels challenged and impelled to action; he has freedom, room for movement, for dashing, leaping, ya-hooing. The level plane not only accommodates, but also induces mass action, as on the polo field, the football field, the soccer field, and the racetrack.

If, upon this unobstructed base, we set an upright plane, it becomes an element of high interest and a point of orientation for the visible field. We are drawn to it, cluster about it, and come to rest at its base. No small factor in this natural phenomenon is man’s atavistic tendency to keep his flanks protected. The vertical plane or wall gives this protection and suggests shelter. Increased protection is afforded by two intersecting upright planes.

They provide a corner into which our 87 atavistic man may back, and from which he may survey the field for either attacker or quarry. Additional vertical planes define spaces that are further controlled by the introduction of overhead planes. Such spaces assume not only their size and shape and degree of enclosure from the defining planes, but also a resultant character induced by the separate planes acting together and counteracting.

This space may be one of tension or repose; it may be stimulating or it may be relaxing. It may be immense, suggesting certain uses, or it may be confining, suggesting others. In any event, we are attracted to those spaces that we feel are suited to our use, be it hiking, target shooting, eating grapes, or making love. We are repelled by, or at least have little interest in, those spaces that appear to be unsuited to the purpose we have in mind.

The Japanese, in their planning, have learned to develop spatial volumes of such intrinsic human scale and personalized character that the spaces can only be satisfied by the presence of the person or persons for whom they were conceived. The Abbot’s garden of Nikko for instance, is only complete when the Abbot and his followers are seated sedately on the low broad terraces, or are wandering contemplatively among the gnarled pine trees or beside the quiet ponds.

The Imperial Shinjuku gardens, sublimely beautiful and faultlessly groomed, seem always somehow incomplete except in the Emperor’s presence. In all Japan, each family home and garden, planned together and as one unit, is a balanced composition of interior and exterior spaces so designed as to call for, and need for fulfillment, the master, his family, and his friends for whom they were created.

Some spaces are man-dominated, and are controlled in size by the reach of his arm or the turning radius of his car. Other spaces are intentionally planned to dominate man. The visitor to the Grand Canyon is brought into relation to the dizzying heights and yawning depths so that he thrills to their maximum impact.

On the Blue Ridge Parkway, in Virginia, man is intentionally brought to the edge of a sheer precipice, and then, on some narrow rocky ridge, is thrust like an ant against the vast, empty dome of the sky. Ancient, mysterious Stonehenge in England, a great circle of space carved out of the moors with massive stone posts and lintels, is a dramatic reminder that even the primitive Druid priests in their dim forgotten centuries already knew the power of the space to inspire and humble man. It would seem that even then they must have sensed that man’s soul is stretched by the feeling of awe, and his heart revitalized by the experience of abject humility.

Between the micro and macro spaces we may plan spaces of an infinite range in size. The volumetric dimensions should never be incidental. We must calculate and contrive those dimensions that will provide the optimum space or spaces for each prescribed human experience.

Spatial form. It has been said that, ideally, in designing or planning, form must follow function. This statement is much more profound than it seems. It is open to some argument unless, as we have previously assumed, esthetic considerations are considered a part of function. What all this means is that any object or thing should be designed as the most effective tool (in form, materials, and finish) to do the job for which it is made; and moreover, it should look it.

If the designer can achieve an actual and apparent harmony of form, material, finish, and use, the object should not only work well, but should also be pleasant to see. Let us take a simple example. An axe handle has for its specific purpose the transmitting to the cutting edge of an axe- head the full power of the axeman’s stroke. A superior handle is made of selected, straight-grained, seasoned ash with just the right degree of toughness and flexibility.

It is shaped to the grip and butted to prevent slipping. From the grip it swells in a strong force-delivering, shatter-resistant curve of studied thickness and length. When the tapered helve is fitted and wedged at precisely the right angle to the head, the axe is in perfect balance, lies well in the hands, and is good to use. It is also good to look at. To the woodsman it is beautiful.

If the woodsman were shown a new axe with a handle made of plastic he would probably shake his head incredulously — a handle that had no grain and looked like glass surely couldn’t be trusted. To him the handle would appear comical, incongruous, and ugly. If, however, by 39 experience he camje to learn that the new handle was in all ways superior, in time he Would come to admire it — and for him no axe with a wooden handle could ever be as beautiful again.

A sloop is designed to utilize the driving force of the wind in propelling a floating object through the water. In the superior sloop the hull is fastidiously shaped to best cleave the waves, slide buoyantly through the water, and leave a smoothly swelling wake; the deep lead keel extends the conformation of the hull as a streamlined stabilizer; the spars of clear pine are so fashioned and bent as to carry the optimum areas of canvas; the humming stays are of finest stainless steel cable; the halyards and sheet are of braided nylon; the chaulks and cleats are so formed as to fairly reach for the lines; tiller and rudder are precisely fitted and balanced to sweep and bear. Such a sloop, heeled and scudding, is a miracle of shapes, materials, and forces working in harmony. Here again form is designed for function — and the form is a beautiful thing. For, as the poet Keats has told us, “Beauty is truth, truth beauty.”

Not only things, but spaces as well, should be given their form with high regard for function. We have seen that this is true of the child’s playlot, of the planned highway, and of the hypothetically ideal city. Without doubt the greatest common denominator of all pleasant site volumes is this very quality.

Having allocated and organized the required use-areas for a project site, the planner proceeds to develop these areas into use-volumes, each volume being designed in size, shape, material, and finish to best express and accommodate the use for which it is planned, and to best relate it to all other project functions and volumes.

Date added: 2025-08-01; views: 192;