Spatial Color. Abstract Spatial Expression

Spatial color. In passing, we might mention an early Chinese theory of volumetric color design. Man, according to this theory, has become so accustomed to the color arrangements of nature that he has an aversion to any violation of the accepted pattern. It follows that, in selecting colors for any man-made space, interior or exterior, the base plane is treated in earthy colors — the hues and values of clays, loams, stones, gravels, sands, forest duff, and moss.

The blues and blue-greens of water, recalling its unstable surface, are used but rarely on base planes or floors, and then only in those areas where walking is to be discouraged. The structural elements of wall and overhead are given the colors of the tree trunk and limb — blacks, browns, deep greys, reds, and ochres.

The receding wall surfaces adapt their hue from the wall of the bamboo thicket, the hanging wisteria vines, the streaming sunlight and foliage of the glade, the pine bough, and the interlacing branches of the maple. The ceiling colors must recall the airiness of the sky, and range from deep cerulean blue or aqueous greens to misty cloud whites or soft greys. This writer has found that this tested theory of nature adaptation applies as well to the use of materials, textures, and forms.

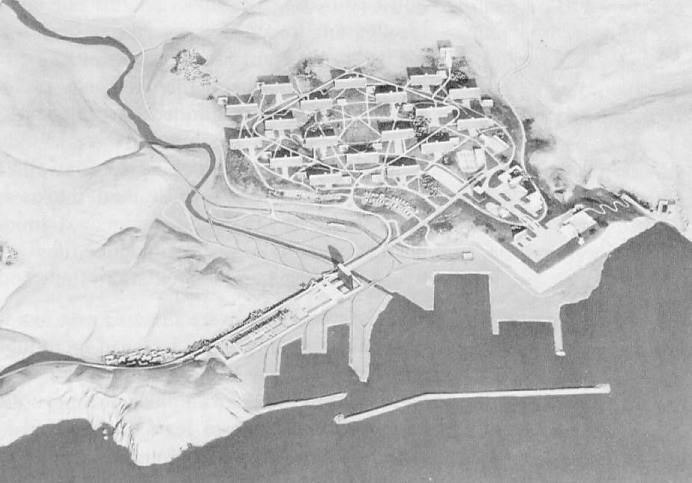

An early study for the new city of Nemours in Algiers by Le Corbusier and P. Jeanneret. Note the complete and sensitive adaptation of all use-areas and structures to the natural topographic forms. Note also the adept way in which use-areas have been translated into use-volumes

There are, of course, many other theories and systems of color application.

One theory would keep the volume enclosure neutral, in shades of grey, white, or black, and let the objects or persons within the room thus “glow” with their own subtle or vivid color. Another theory calls for infusing a space or coloring a form with those hues and values that, alone or in combination, produce a prescribed intellectual-emotional response.

Given a basic color theme or melody, it modulates harmonious overtones to soothe, contrasting ones to interest, and discordant ones to incite. Another system manipulates spaces, and objects within those spaces, by the studied application of recessive and dominant values and hues.

Another would determine for any given structure one expressive color which, running through the whole, could be used as a dominant unifying trunk. All other colors would be, to this trunk, its branches, twigs, leaves, flowers, and fruit. In such a scheme can be sensed a cohesive organic system of color like that of the willow, the sassafras, the mountainside, the river valley, or any other element or feature of nature.

Still another theory proposes that hues and values have no meaning except in combination, and gain their impact through carefully devised relationships. All systems of color theory attest to the truth that spaces, or things within the spaces, have no meaning except as they are experienced, and that, in creating spatial experiences, the knowledgeable handling of color is essential.

Abstract spatial expression. We have learned that, just as abstract design characteristics may be suggested by a given landscape type, abstract spatial characteristics may be suggested by a given function. The spatial characteristics of a cemetery, for instance, would hardly resemble those of a Coney Island-type park. We come to the amusement park for a laugh, for a shock, for a change, for relief and escape from ordered routine.

We want to be fooled, and delight in confusion and distorted, contorted, ridiculous shapes. We seek the spectacular, the spinning, tumbling, looping, erratic motion. We love the roller coaster’s flash and roaring crescendo, the brassy clash of cymbals, the jarring sock-ring-a-ling-ting of the tambourines, the rap of the barker’s hammer, and the raucous honkytonk. We thrill to color as gaudy as grease paint, as garish as scarlet and orange tinsel, as raffish as dyed feathers, gold sequins and rainbow-hued glitter. We expect the scare, the boff, the flirt, the shriek, the come-on, the tease, and the taunt. All is gay tumult; all is for the moment; all is happy illusion.

We accept materials as cheap and as temporary as bunting and whitewashed two-by-fours. Everything is surprising, attracting, diverting, winding, expanding, contracting, arresting, amusing, and dynamic — carnival atmosphere. If we want a successful amusement park, this atmosphere must be planned. We must create it with all the planned whoop-de-doo and spatial zis-boom-bah that we can conjure into being. This is not just desirable; in such planning it is vital. Here, order and regimentation are wrong, and the stately avenue or the handsome mall would be in fatal error.

How different are the spatial requirements of a cemetery. The cemetery volumes we would expect to be serenely monumental, spacious, and beautiful. We would expect some imposing enclosure, to provide protection and imply detached seclusion. The entrance gates, like the prelude to an anthem, would give theme to the spaces within, for these are the earthly gates to paradise. Man enters here in his moments of most poignant sorrow, seeking to bury his dead in solemn ceremony, as has man from time’s beginning.

He comes in grief, seeking that which will give solace and comfort. The general spatial character of a cemetery might well suggest peaceful quietude in terms of soothing muted colors, subtle harmonies of texture, soft rounded forms, horizontal planes, still water, the ethereal, and the evanescent.

Troubled and questioning, man seeks here reassurance and order. Order as a spatial quality is affected by evidence of logical progressions, visual balance, and ordered cadence of plan or spatial revelation.

Humbled and distraught by the presence of death he would orient himself to some superior power. The presence of such divine power may be suggested in plan form and by symbol. A sensitive variation of the classic axial treatment that so compellingly relates man to a concept perhaps has no better application than here. There may well be closed spaces for contemplation and introspection. There may also be breathtaking vistas and sweeping views, so long as vista and view are in keeping with the sacred and the sublime.

At those thoughtfully selected plan areas where an inspirational quality is to be concentrated or brought to culmination we might use the soaring verticals that effect an uplift of the spirit. Again, an appropriate sculptural group placed at the edge of a dark reflective surface, or a simple cross of white marble lifted against the sky may evoke in the viewer an emotional response of great satisfaction and meaning.

Man seeks here a fitting and final resting place for those whom he has loved. In planning, this concept is translated into terms of the eternal and the ideal. The eternal may be suggested by planned harmony with the timeless features of the landscape — the moss, the fern, the lichened rock, the sun, the grove of gnarled and venerable oaks, the gently sloping summit of a hill.

Materials must be enduring, such as marble, granite, and bronze. Idealism may be expressed through the enlightened creation of those spaces and those high art forms that will instill in man the firm conviction that here in this sacred place the living and dead are truly in the presence of their God.

Many will note that these spatial requirements are similar to those of a church chapel or sanctuary; and, just to the extent that they are similar, will the church form and spaces resemble architecturally their cemetery counterpart. These qualities refer to no one particular cemetery more than any other. They are, rather, the abstract spatial qualities suggested by the function of all cemeteries.

In like manner, any such function we may name — the shopping center, the summer camp, the outdoor civic light opera — will immediately bring to our mind desirable spatial characteristics. These, it should be apparent, are pertinent to the planner.

Date added: 2025-08-01; views: 214;