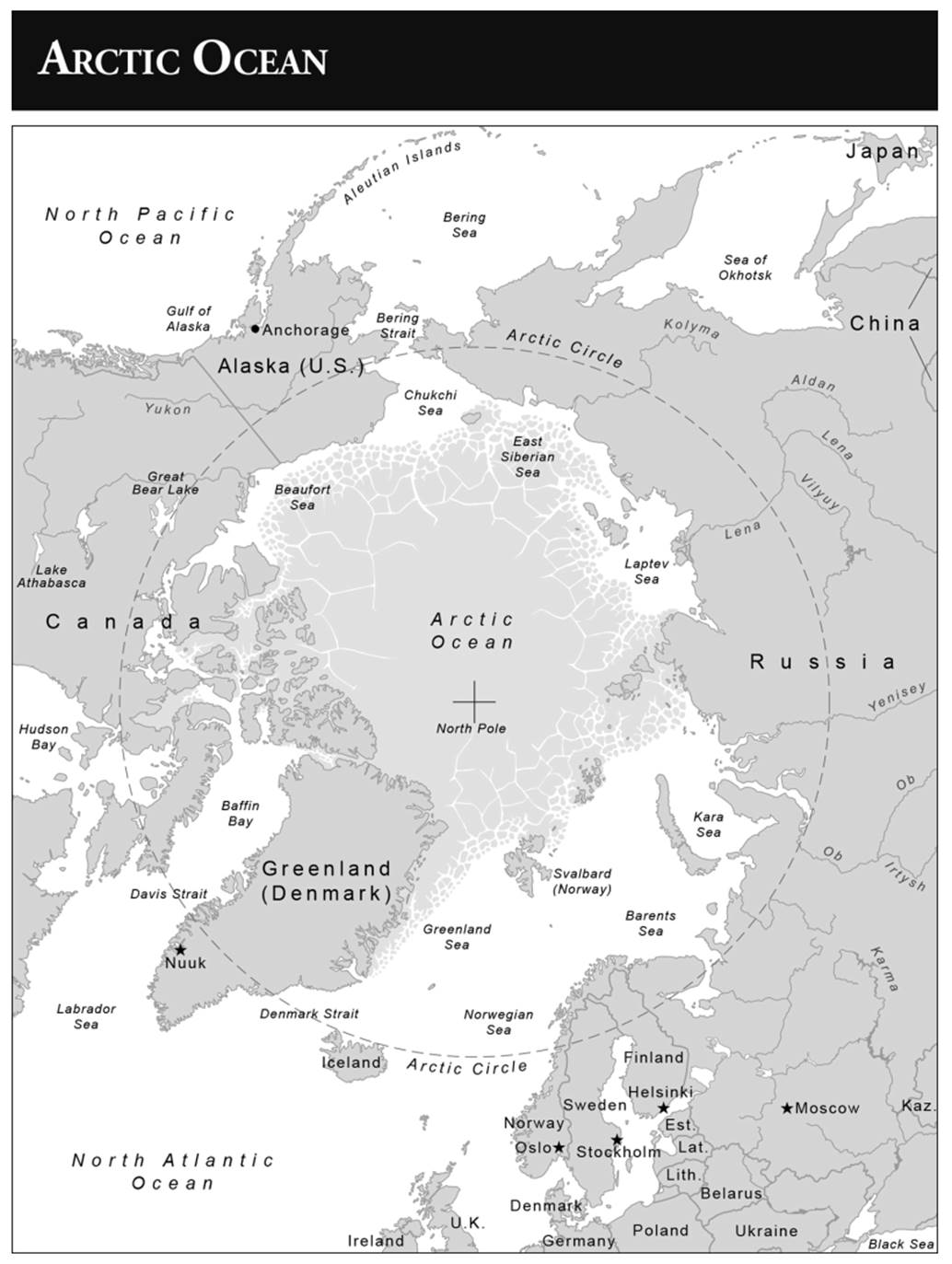

Climate Change and the Arctic Ocean

In the past century and a half, human activities have dramatically changed the global climate and have begun to heat the Earth. Changes stemming from anthropogenic climate change perhaps are most noticeable in the Arctic Ocean. Satellite monitoring by several agencies has revealed that with each phase of global warming and cooling, the amount of free-forming ice within the Arctic changes noticeably. In the past 100 years, the average temperature on Earth rose approximately 1.5°C.

This may not seem like a large global temperature increase, but within the Arctic Ocean, the temperature has risen approximately 0.6°C per decade for the past thirty years—this is roughly twice that of the Earth. During roughly the same span of time, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) used passive microwave data to study the ocean’s ice “minimums,” or when the ice is at its lowest surface area coverage during the summer months. This research has shown that the minimum area has decreased from approximately 6.5 million km2 to 3.6 million km2. To put that in perspective, according to NASA satellites, the ocean depth has increased approximately 7.4 cm since 1992. Translating that value into something more tangible, the amount of water transferred by melting ice into the ocean would be enough to replace the water in the entire Baltic Sea, with enough left over to fill roughly 2.4 billion Olympicsized swimming pools. Translating this incredible increase into projected long-term effects is one way in which scientists measure the impact of climate change.

With the melting of the Arctic Ocean icescape, the ecosystem and its biodiversity are dramatically affected. Look no further than the mighty polar bear (Ursus maritimus). The polar bear uses the sea ice to hunt for its primary food source, marine mammals. The polar bear traversed the once vast landscape of Arctic Ocean ice in search of bearded and ringed seals. Now, with the declining icescape, the bears are unable to reach many hunting areas and, as a result, their access to crucial food supplies is limited. This is in direct correlation with their territory and inversely related to their competition. With the limited territorial domain, more and more polar bears will be forced to compete over a smaller food supply.

Weather patterns are affected by the melting ice as well. The change in oceanic salinity creates a cyclic problem. Salinity levels are inversely proportional to the evaporation and precipitation of water. Current models based on a fifty-year study dating back to 1950 show an intensified global water cycle at 8 ± 5 percent per degree of surface warming. The modeling and testing conducted over that fifty-year period show patterns of dry areas becoming drier and wet areas becoming wetter, meaning an expansion of desert areas and more rainfall or storm systems in rainforests and over the oceans.

Date added: 2025-08-31; views: 215;