The Indian Ocean: A Cradle of Globalization and Modern Challenges

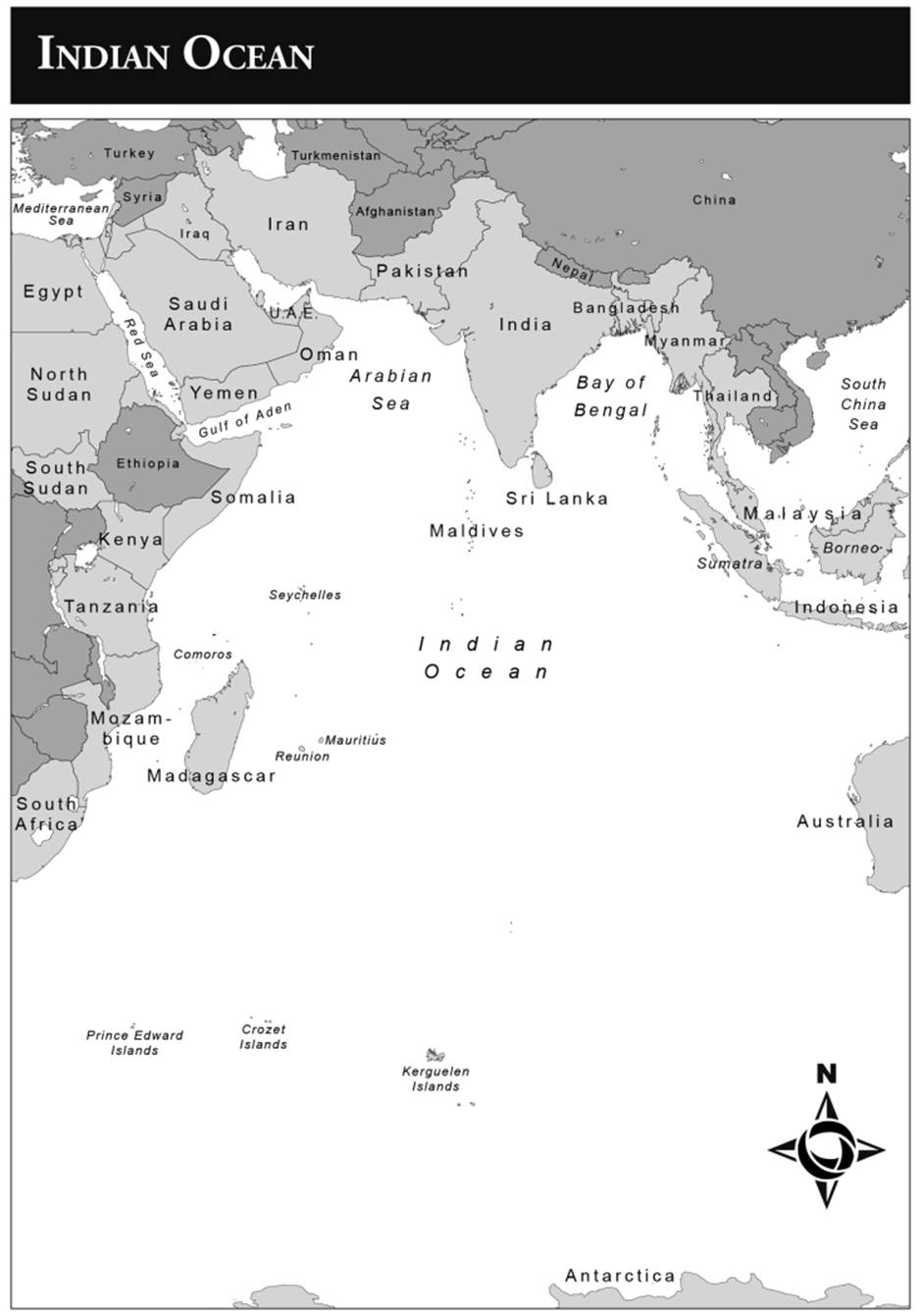

Introduction. The Indian Ocean is the third largest of the five global oceans, reaching 41,337 miles of coastline, covering 26.5 million miles2, and measuring about five and a half times the size of the United States. It stretches from the east coast of Africa to the west coast of Australia and from South Asia to 60°S latitude, where it borders the Southern Ocean. The currents and weather patterns of the Indian Ocean are shaped by tropical and subtropical climate conditions. Its continental shelves are typically narrow, dropping off steeply into a series of underwater plains and basins.

The ocean’s major mountain ranges are the Mid-Indian Ridge, arcing from just off the coast of the Arabian Peninsula to the south, and the Ninety East Ridge, stretching 3,100 miles west of Indonesia and Australia. Its lowest point is the Sunda Trench (previously known as the Java Trench), which lies south of the Indonesian island of Java. The islands of Madagascar, the Seychelles, the Maldives, Kerguelen, and the Chagos Archipelago are part of plateaus, whereas others, including Reunion, Mauritius, and much of Indonesia, have volcanic origins. The Lakshadweep and Maldives archipelagos and the Cocos Islands consist of atolls made up of coral islands.

The complex past of the Indian Ocean and its sea-oriented cultures cannot be understood in isolation from the semiannually reversing monsoon winds, which—before the invention of steam-powered watercraft—determined when and where sailors could navigate. In the warmer months, the temperatures of the Asian landmass rise more quickly than those of the ocean, creating a pressure gradient that causes southwestern winds and heavy monsoon rains to move toward Asia’s southern shores. In the colder months, conversely, air masses above the Indian Ocean are warmer than those above Asia, because ocean water takes much longer to cool than land does.

This draws cool northeastern winds and moisture toward the equator, enabling seafaring journeys in the opposite direction. In between the two monsoon seasons—typically in May, June, October, and November—cyclones are common across the intertropical convergence zone, which includes the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea. Farther away from the continents, westerly winds dominate the southern Indian Ocean, causing frequent storms where currents converge.

The Indian Ocean was the first ocean to facilitate human expansion. It is therefore arguably this planet’s most “globalized” and culturally significant body of water. When anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) migrated out of Africa 85,000 to 90,000 years ago, some of their first journeys traced the shores of the Indian Ocean. They crossed the Red Sea to the Arabian Peninsula, the Strait of Hormuz to Asia’s southern shores, and the Wallacean straits to what is now Australia. Over thousands of years, as agricultural and navigational skills improved, the history of the so-called “Indian Ocean world” was further shaped by trade and exploration. Beginning about the third millennium BCE, its coastal waters were regularly plied by Middle Eastern, Indian, and Southeast Asian sailors. As these small-scale networks very gradually toppled over into full-fledged world systems, the maritime trade in spices, textiles, and foodstuffs was followed by the exchange of cultures, religions, and ideas. In the late fifteenth century, when the Portuguese first entered this global axis of human interaction, they encountered a thoroughly cosmopolitan milieu featuring Swahilis, Arabs, Persians, Gujaratis, Tamils, Malays, and many other groups. The European colonization of Africa and Asia only reached full force by the nineteenth century.

Trade continues to be ubiquitous in the contemporary Indian Ocean, with petroleum from Middle Eastern nations and Indonesia now being its most essential commodity. The Indian Ocean presently hosts about 40 percent of all global offshore oil production. Other common resources include sand and gravel for construction, as well as beach sands and offshore placer deposits containing various minerals. The most intensively used ports include Chennai (India), Colombo (Sri Lanka), Durban (South Africa), Jakarta (Indonesia), Port Klang (Malaysia), Kolkata (India), Melbourne (Australia), and Mumbai (India). Fish and shrimp, long a staple of peoples living along the Indian Ocean’s coastlines, now also feed a growing global demand for seafood. Along with exports from bordering countries, vessels from Russia, Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan catch large amounts of fish, especially shrimp and tuna.

In a cruel twist of history, the same globalizing forces that gave the Indian Ocean its erstwhile importance now precipitate its devastation. Overfishing has caused populations of certain species to plummet, while also endangering whales, seals, sea turtles, and dugongs. Pollution from pesticides, fertilizers, and chemicals that run off from surrounding lands and rivers has caused further harm to sea life, as have offshore oil and chemical spills. Other environmental issues facing the Indian Ocean include large collections of plastic garbage trapped in its currents and warming water temperatures that have begun to cause destructive coral reef bleaching. Disasters not caused by humans have also taken their toll. In December 2004, many coastal areas in countries facing the ocean suffered widespread destruction when they were inundated by the devastating Indian Ocean tsunami.

Whale Hunters of Indonesia. Villagers of Lamalera in the eastern Indonesian archipelago have hunted whales for more than four centuries. Today, they are among the only indigenous communities in the Indian Ocean to hunt whales routinely, and they do so largely for subsistence. Their method of capture is to pursue the whales in the open ocean using sailing vessels, and then a man will leap from the bow with a harpoon to spear the whale.

After a usually lengthy and dangerous effort, the whale is then towed to shore and processed for its meat, oil, ambergris, spermaceti, etc. Little or nothing is wasted. Given the incredibly dangerous nature of the hunts, it is not surprising that the whale hunters have, over time developed a range of prohibitions they believe will help protect them at sea. Once a whale has been harpooned, for example, crewmen may not drink, smoke, swear, converse, or relieve themselves until the whale is dead. Hunters are also forbidden from using the names of places or living persons. Most crucially, sailors may not speak of distant lands or peoples, lest the speared whale pull the boat farther out to sea or the ocean current switch abruptly and carry the boat away.

Other superstitions guide Lamalera fishing patterns. If a whale is divided among the crew unfairly, the boat will fail in its efforts until the transgressor washes his mouth (formerly with blood, today with holy water). Likewise, if people in the village fight while the boats are out or children are too noisy where the boat is kept, that boat will fail to capture a whale. The crew will also call upon the names of distant ancestors to help prevent the whale from damaging the boat or injuring the crew and to request that the whale submit quickly. Lance Nolde.

Indian Ocean Studies: Beyond Geography & Trade

In view of its incessant global significance, the Indian Ocean provides fodder for various types of researchers. Following a long legacy of scholarly neglect, the area has now been explored so much that its study has itself become a topic of research. Proposed new ways of looking at this connective space are almost as ubiquitous as the symposiums, conference panels, seminars, workshops, and edited volumes dedicated to it.

The Indian Ocean continues to provide promising research avenues for those interested in historical connections, archaeology, anthropology, diaspora studies, literature, linguistics, human genetics, plant sciences, geopolitics, global security, transnationalism, maritime resources, sustainable development, and many other topics. No attempt can be made to give even the most basic overview of these studies while still respecting this volume’s word limit. Instead, I will take a narrower scope and make the case that cultural contact is key to understanding the Indian Ocean World as a whole, drawing upon multiple ways in which the region’s past has been studied and could be studied in the future.

Before doing so, it is necessary to first briefly address the institutional context in which the Indian Ocean has been conceptualized in the past. Colonial-era publications on this region rarely consisted of more than Eurocentric travelogues, sailors’ manuals, and commentaries of “Oriental” texts. Many of these early works unfavorably contrasted the “immutable” East with the “dynamic” West. The Indian scholar K. M. Panikkar and the Mauritian scholar Auguste Toussaint—in quite distinctive ways and with different focuses—can be considered the first to approach the Indian Ocean as the historically interconnected area it is. Comparably exhaustive monographs are of much later date. By the 1980s, Indian Ocean thinking had become profoundly influenced by Immanuel Wallerstein’s world-system theory, as well as the longue durSe social history of the French Annales School. Indeed, many scholars gratefully acknowledge the impact of Ferdinand Braudel’s game-changing work on Mediterranean history on their conceptualizations of the Indian Ocean.

These valuable works notwithstanding, one of the field’s key questions remains conspicuously unanswered: To what extent does the Indian Ocean constitute a cultural area? Or, in other words, “what characteristics and human experiences and practices are shared across the basin?” This directly affects the legitimacy of the Indian Ocean as a separate field of institutionalized study. Why should the region’s past be studied comparatively? What insights does such an effort reveal that cannot be obtained through the lens of world history more broadly? In economic terms, one may argue that the Indian Ocean has progressively integrated into a more or less unitary world-system.

There are also important religious connections, which in turn influenced the ocean’s economic and legal landscapes. It is less clear to what extent these necessity-driven exchanges yielded “a zone of cultural negotiation,” if not “an inter-regional arena of economy and culture.” Kenneth McPherson holds that “no historian has successfully argued for a regional identity for the Indian Ocean beyond a commonality of essentially economic practices which, it could be claimed, are universal, even if their external forms vary from one civilization to another.” Although the author calls attention to a number of cultural commonalities, he rejects the idea of a unitary area.

So, does the concept of an Indian Ocean World solely reflect geographical determinism? Are we dealing with a “fake” entity, internalized by the academic community who continue to reify it as a definite thing? Even its name has raised eyebrows, as it suggests—rather than demonstrates—Indian predominance and downplays the historical importance of Africa or Southeast Asia. In addressing the issue of unity, some scholars highlight geographic factors. From time immemorial, the climatological conditions described previously gave rise across the Indian Ocean basin to distinct maritime orientations and commercial specializations. Thus, it is hardly far-fetched to speculate that cultural similarities attested across its shores reflect not only shared environmental influences (“territoriality”) but also long-distance interethnic contacts (“relationality”). The interrelatedness of maritime lifestyles, port cities, and cultural diffusion is well-known. In the Indian Ocean, as elsewhere, the most cost-efficient mode of travel, transportation, and communication between geographically distant communities has generally been by ship. We should therefore keep a substantial focus on the sea and seafaring to explore what connects the cultures of the Indian Ocean basin.

This “aquatic turn” in Indian Ocean studies also provides a symbolism to come to grips with the region’s geographic fluidity. Here, Braudel’s study of the Mediterranean is once again worthy of emulation. He contends that the boundaries of this sea expanded and shrunk—“pulsed,” in his terminology—over time. If we apply this idea to the Indian Ocean, we may ask ourselves which regions are to be included in its cultural orbit. How far did it stretch westward, into the Mediterranean, or eastward, into Southeast Asia? Do we include Guangzhou, with its historical (and ongoing) presence of mercantile communities from various Indian Ocean ports? Cape Town arguably became part of the Indian Ocean World in early modern times, whereas Australia’s entry must be dated after the Industrial Revolution. With its several diasporic communities, can a Western metropole like New York City be seen as part of the Indian Ocean World?

When examining what these far-flung places have in common in terms of culture, it makes sense to also consider what sets them apart. This essay will therefore focus first on connections and disjunctions across the Indian Ocean World before proceeding to foreground the movement as a unifying force. This allows for some conclusions on cultural contact in an Indian Ocean context and ways to study it.

Date added: 2025-08-31; views: 258;