Platonic Astronomy: How Plato's Philosophy Defined Ancient Greek Scientific Research

The fragmented speculations of the pre-Socratic natural philosophers gave way to a more unified and problem-driven approach in the fourth century BCE, primarily through the influential syntheses of Plato and Aristotle. Prior to Plato, Greek cosmology exhibited remarkable diversity without consensus. For instance, Anaximander of Miletus envisioned a disk-shaped earth floating in space, with celestial bodies as fiery wheels containing holes, while Pythagorean cosmology displaced the earth from the cosmic center entirely. These early, often mechanistic models were distinctly Greek inventions but lacked any sustained program of detailed development or verification, remaining isolated theoretical proposals.

Plato of Athens (428-347 BCE) fundamentally redirected the course of natural philosophy, particularly astronomy. A student of Socrates, Plato institutionalized philosophical inquiry by founding the Academy, a school adorned with the motto, “Let no one enter who is ignorant of geometry.” For Plato, geometry represented the perfect, abstract Forms that constituted true reality, a belief he extended to the cosmos. He disdained observational astronomy but presented a complex cosmological model in his dialogue "Timaeus", portraying a universe of spinning shells carrying heavenly bodies around a central earth, all imbued with a divine life force.

Plato’s paramount contribution was not his specific model but the profound theoretical problem he defined for astronomers. On first principles, he asserted that heavenly bodies must move with uniform circular motion because the cosmos is a reflection of perfect, eternal Forms. This philosophical commitment clashed directly with the observed "stations and retrogradations" of planets—their apparent looping, non-uniform paths. Plato thus tasked astronomers with "saving the phenomena", meaning devising geometric models using only uniform circular motions to explain the planets' irregular appearances, thereby creating a focused research agenda where none had systematically existed before.

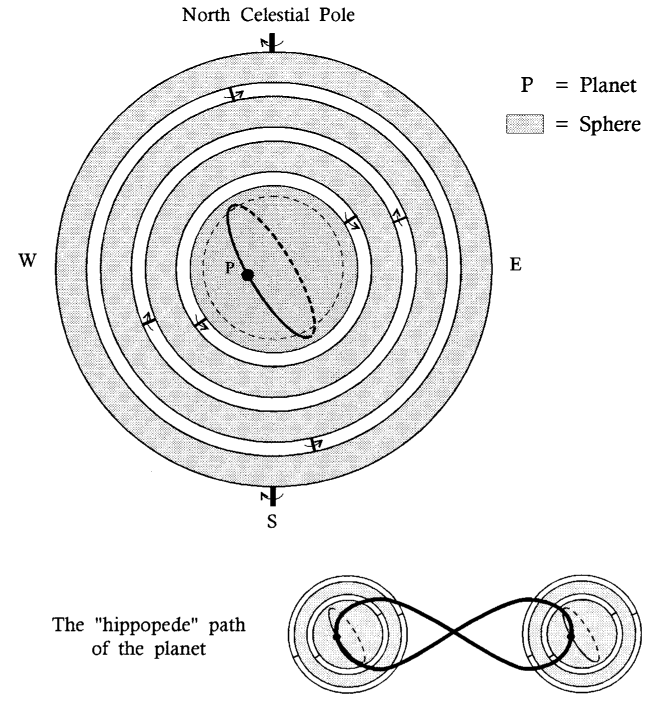

This mandate spawned a dedicated research tradition. Plato’s student, Eudoxus of Cnidus (fl. 365 BCE), responded with the first major geometric model: a system of twenty-seven homocentric spheres nested like a cosmic onion around the earth (See Fig. 4.4). Different sets of rotating spheres accounted for each planet’s motion, with a specific pair generating a figure-eight path called the "hippopede" to explain retrograde loops. Successors like Callipus of Cyzicus (fl. 330 BCE) and Aristotle (384-322 BCE) refined this model, adding spheres to improve accuracy, with Aristotle’s version employing fifty-five or fifty-six spheres to address mechanical inconsistencies.

Fig. 4.4. Eudoxus’s system of homocentric spheres. In Eudoxus’s “onion” system, Earth is at rest in the center of the universe, and each planet is nestled in a separate set of spheres that account for its daily and other periodic motions across the heavens. From the point of view of an observer on Earth, two of the spheres produce the apparent “hippopede” (or figure-eight) motion that resembles the stations and retrogradations of the planets

Although the Eudoxean model of homocentric spheres was ultimately supplanted in later antiquity, its historical significance is profound. It demonstrates how scientific research depends on a shared theoretical consensus—here, Plato’s paradigm of uniform circularity—that guides a community of practitioners. Eudoxus, Callipus, and Aristotle were not merely theorizing; they were engaged in detailed, quantitative model-checking dictated by their philosophical commitments. This tradition underscores the community-based nature of the Greek scientific enterprise, marking a pivotal shift from isolated speculation to a sustained, collaborative effort to reconcile mathematical theory with celestial phenomena.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 2;