Ancient Astronomy and Calendrical Science in Early Civilizations

All agricultural civilizations developed sophisticated calendrical systems rooted in astronomical observation. These systems were pragmatically essential for regulating agrarian activities, religious rituals, and commercial contracts. The drive for calendrical accuracy consequently spurred advanced astronomical research within these early societies, establishing a foundational link between practical necessity and scientific inquiry.

Calendrical Systems of Mesopotamia and Egypt. In Mesopotamia, a highly accurate calendar was established by 1000 BCE. By 300 BCE, experts had created a mathematically abstract, long-term calendar. Using a lunar calendar of 354 days, they synchronized it with the solar year by intercalating an extra month seven times every 19 years. Conversely, ancient Egypt employed a solar civil calendar of 365 days (twelve 30-day months plus five festival days). This calendar drifted by one-quarter day annually, realigning with the solar cycle every 1,460 years. This seemingly unwieldy system functioned because the critical annual Nile flood was predicted independently by observing the heliacal rising of the star Sirius.

The Unity of Early Scientific Knowledge. Calendrical astronomy, astrology, meteorology, and magic formed an inseparable body of knowledge in Mesopotamia, Egypt, India, China, and the Americas. Contrary to modern distinctions, astronomers and astrologers were often the same individuals. Predicting seasonal cycles, crop yields, or royal fortunes was viewed holistically as useful, practical knowledge, demonstrating a universal pattern of studying nature for applied ends.

The Pinnacle of Babylonian Astronomy. Babylonian astronomy represents the most developed ancient scientific tradition. A shift toward astral religion likely encouraged meticulous heavenly observation, with continuous records dating from 747 BCE. By the fifth century BCE, astronomers could predict planetary motions, solstices, equinoxes, and solar and lunar eclipses. Their legacy is profound, contributing the sexagesimal system, the division of the circle into 360 degrees, the seven-day week, and planetary identifications. Their technical methodologies were later adopted by Greek and Hellenistic astronomers.

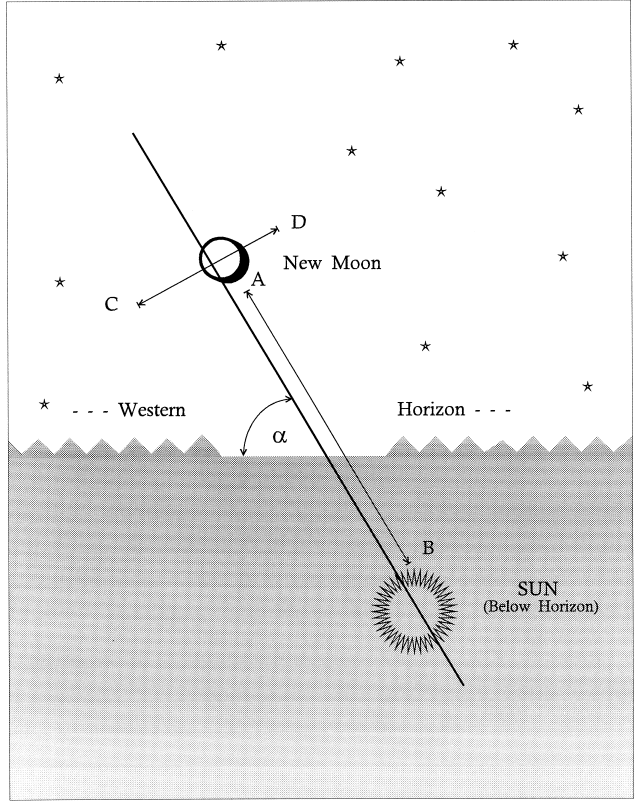

Case Study: The New Moon Problem. Babylonian research is exemplified by their solution to the "new moon problem." For calendrical and religious precision, they needed to predict whether a lunar month would last 29 or 30 days. This depended on several variables: the relative sun-moon distance (AB on the figure), the season (a), and longer lunar cycles (CD). Through systematic observation and mathematical modeling, they created accurate predictive tables. This focused research highlights their transition from mere observation to theoretical analysis, prioritizing abstract cyclical models over direct visual phenomena.

Fig. 3.7. The earliest scientific research. Ancient Babylonian astronomers systematically investigated variables determining the first appearance of the new moon each lunar month. More than simply observing the phenomena, Babylonian astronomers investigated patterns in the variations of these factors, reflecting a maturing science of astronomy

State-Supported Knowledge: Medicine and Alchemy. State bureaucracy also institutionalized other useful knowledge. Official medical practitioners, supported by the state, advanced empirical understanding of anatomy, surgery, and herbalism. The Edwin Smith medical papyrus (c. 1200 BCE) exemplifies early "rational" medical approaches. Similarly, alchemy, rooted in ancient metallurgical technology, received early patronage for its perceived utility, blurring modern lines between the rational and the pseudoscientific.

Cosmologies and Worldviews. The cosmologies of early civilizations were predominantly religious and magical. Heavens were divine realms: in Egypt, the sky goddess Nut held up the firmament; in Babylonia, planets represented gods; Maya cosmology envisioned the earth as a giant reptile. While the Chinese held more organic cosmic views, none developed abstract, mechanical, or naturalistic theoretical models of the cosmos as a whole. The concept of "nature" as an independent object of study was largely absent.

The "Science of Lists". These civilizations often treated knowledge extensively through encyclopedic lists—cataloguing gods, plants, animals, and cities in a practice termed the "science of lists." This compilatory approach, possibly preceding formal logic, required significant state resources to maintain battalions of scribes, highlighting the administrative context of early knowledge preservation.

Conclusion: The Emergence of Science with Civilization. In summary, science emerged repeatedly with civilization, driven by practical needs. Writing and arithmetic were transformative technologies for solving problems. State-supported institutions and specialist experts enabled advanced calendars, sophisticated astronomical problem-solving, and mathematical exploration. However, these early sciences generally lacked the abstract dimension of theory. The pivotal evolution toward natural philosophy—the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake—would originate uniquely with the Greeks, building upon these ancient, utilitarian foundations.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 2;