Egyptian Pyramids: Engineering, Statecraft, and the Hydraulic Civilization

Monumental architecture, including pyramids, temples, and palaces, is a definitive hallmark of high civilization and a pivotal chapter in the history of technology. These structures represent extraordinary technical accomplishments and signify the formal institution of architecture alongside advanced engineering trades. The Egyptian pyramids stand as the classic example, offering a well-documented case that encapsulates the relationship between intensive agriculture, civilization, and the Urban Revolution.

Consider the sheer immensity of the Great Pyramid at Giza. Constructed for Pharaoh Khufu (Cheops) during the Fourth Dynasty's zenith (c. 2589–2566 BCE), it remains the largest solid-stone structure ever built. It contains an estimated 2.3 million limestone blocks, averaging 2.5 tons each, with a total volume of 94 million cubic feet and a weight nearing 6 million tons. Originally standing 485 feet high on a 13.5-acre base, its precise north-south and east-west alignment demonstrates sophisticated practical mathematics and engineering prowess.

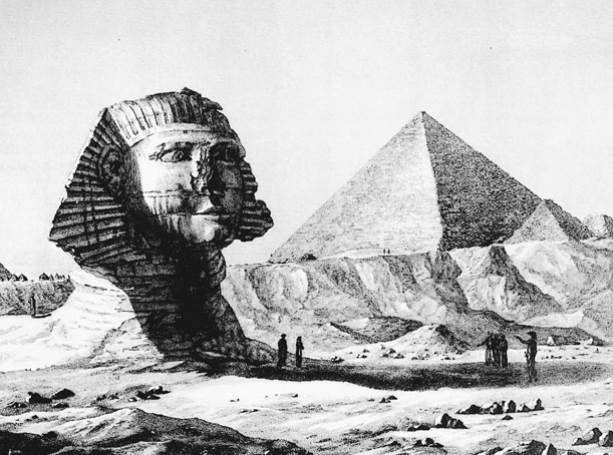

Fig. 3.2. The Great Pyramid at Giza. An engineering marvel of the third millennium bce, the Great Pyramid of Cheops (Khufu) at Giza culminated the tradition of pyramid building in Egyptian civilization. Some modern interpreters see it as a monumental exercise in political “state building.” The Cheops pyramid is on the right

Construction was a staggering organizational feat. The Greek historian Herodotus reported 100,000 laborers working for twenty years, though modern estimates suggest a core of 4,000–5,000 skilled workers year-round, supplemented by seasonal conscripts. Techniques relied primarily on Neolithic building methods amplified by the state's power: copper tools, wooden sledges, earthen ramps, and immense coordinated labor. This scale of deployment, orders of magnitude greater than earlier societies, was characteristic of the new agrarian state's capabilities.

The Great Pyramid did not emerge in isolation but culminated a clear evolutionary progression. This progression began with stepped structures like the Step Pyramid of Djoser and advanced through transitional forms. Early attempts, such as the pyramid at Meidum, ended in structural failure due to an excessive 54-degree slope. The subsequent "Bent" Pyramid at Dashur, built by King Sneferu, reveals a mid-construction correction from 54 to 43 degrees, reflecting learned engineering principles that informed the successful Red Pyramid and later giants at Giza.

Fig. 3.3. The pyramid at Meidum. Built at a steep angle, the outer casing of the pyramid at Meidum collapsed around its central core during construction

Explanations for this frenetic building period extend beyond their function as pharaonic tombs. The sheer volume of construction—thirteen pyramids built by six pharaohs in just over a century—suggests a deeper sociopolitical purpose. From an engineering perspective, pyramid building constituted a continuous state-run public-works project. It mobilized the population during the agricultural off-season, specifically the annual Nile inundation, without disrupting crop production.

This interpretation views pyramids as exercises in statecraft and institutional muscle-flexing. The availability of a large, seasonally idle labor pool allowed multiple pyramids to be built simultaneously. Furthermore, pyramid geometry naturally requires fewer workers at the apex than the base, enabling labor redistribution to new projects as construction advanced. Thus, the pyramids served to reinforce the state's ideology, centralize authority, and circulate resources within a managed economy.

Fig. 3.4. The Bent pyramid. The lower portion of this pyramid rises at the same angle as the pyramid at Meidum, but ancient Egyptian engineers reduced the slope for the upper portion to ensure its stability. The Bent and Meidum pyramids were apparently constructed concurrently with engineers decreasing the angle of the Bent pyramid once they learned of the failure at Meidum

The hydraulic civilization model is key to understanding this dynamic. The pyramids' construction coincided with the peak of political centralization in Old Kingdom Egypt. By organizing and sustaining such colossal projects, the state strengthened the very economic and social systems that supported irrigation agriculture in the Nile River Valley. The pyramids were, therefore, both symbolic and literal instruments of state building, consolidating power while physically employing the surplus generated by controlled riverine agriculture.

Ultimately, the Egyptian pyramids stand as testament to a society that mastered logistics, engineering, and labor organization. They were tombs, but more significantly, they were engines of economic and political integration. Their construction reinforced the centralized state necessary for managing Egypt's hydraulic agricultural base, making them enduring monuments to the intertwined forces of technology, environment, and power in early civilization.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 2;